Emergency Medicine and Trauma Care Journal

Review Article

Enhancing the Educational Experience of Mortality and Morbidity (M & M) Rounds in the Emergency Department (ED)

Fatimah L*

Department of Emergency Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore

*Corresponding author: Lateef Fatimah, Department of Emergency Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Tel: +6563214972/3558; Email: fatimah.abd.lateef@singhealth.com.sg

Citation: Fatimah L (2019) Enhancing the Educational Experience of Mortality and Morbidity (M & M) Rounds in the Emergency Department (ED). Emerg Med Trauma Care J: EMTCJ-100013.

Received date: 15 October, 2019; Accepted date: 25 October, 2019; Published date: 15 November, 2019

Abstract

Morbidity and Mortality (M and M) rounds have been around since the 20th century. When used appropriately, the M and M rounds offer a rich learning ground whereby traditionally, cases are discussed and this enable clinician to go through the mis-calculations or mis-steps their colleagues experienced as lessons so as not to commit similar errors. There is currently no fixed format, nor structure in the conduct of the M and M rounds. Many have followed tradition and continue to discuss the list of mortality and some serious morbidity cases. At the Department of Emergency Medicine (DEM), Singapore General Hospital (SGH), we keep the session dynamic and flexible and recently a review was conducted to enhance the educational experience at the M and M rounds. It was a transformation process and the authors led a group in performing this. A pre-M and M committee was convened to review cases prior to the session, which also served as a peer-review session. A more structured format with presentation template was also added. New segments were also brought in to discuss ethics and Human factors, relevant to the Emergency Department context.

The authors share her experience in the transformation, the reasons for doing this and how the changes were negotiated to involved the whole department in an inter-professional way.

Keywords: Mortality; Morbidity; Patient safety

Introduction

The first documented mortality and morbidity (M &M) rounds started in the 20th century at Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston, United States. Ernest Codman, a surgeon initiated the idea with a view to track patients in their clinical progress and at the same time, be able to identify any errors and lapses in their management. It was conducted with the hope that such errors could be prevented from happening again in future. He envisioned it as a process whereby the medical profession could learn from each other [1-4]. The concept continued to remain controversial, with some institutions adopting it on an ad hoc basis [4,5]. In 1983, when The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) made M & M review a mandatory process for Residency training programmers and certification, it began to be adopted on a more widespread basis. It gradually became a key performance indicator in many recognized institutions across the globe [4-6]. What was less talked about and even more scarce in the literature, was the way these M & M sessions were conducted. The format was really up to the individual organizing the sessions. The structure was not fixed, nor standardized. At times it turned into sessions to ‘blame and shame’, in certain disciplines. Others used it to go through their list of deaths and errors, sometimes without much reflection on the learning objectives [4-8]. When used appropriately, the M and M rounds offer a rich training and learning ground whereby traditionally, cases are discussed and thus, enable clinicians to go through the mis-calculations or mis-steps their colleagues experienced as lessons and learning pointers so as not to commit similar errors [5,6]. More recently, the Ottawa M & M model was proposed and publicized and it added some structure and format to the whole process of conducting these sessions [9].

Morbidity and Mortality Rounds at the ED

At the Department of Emergency Medicine, Singapore General Hospital (SGH), M & M rounds are conducted on a monthly basis. From its early day of routinely going through all deaths that occurred in the ED, it had evolved to sharing on adverse events, morbidity cases, interesting cases and even updating everyone on research projects and new protocols. The objectives were clear and these were mainly focused on: patient safety, patient-centric quality of care (in-line with the institution tag line of; “Patients, At The Heart of all We Do”), and patient-focused initiatives. M & M rounds are a requirement passed down by the Ministry of Health in Singapore and it is counted as a peer-review session for doctors and specialists. It is also a requirement for Joint Commission International (JCI) accreditation.

More recently, at SGH, our Safety and Quality Benchmarking Committee also conducts a Morbidity Review Landscape Survey which comprises the following 13 questions for departments to use as a checklist for guidance (see below). It helps provide some structure and enable departments to reflect on some elements that may not have been considered before.

The Current M and M in the department comprises of the following:

Methodology

Whilst there are many critical elements to be included in any M and M session, the evolution and transformation needed to incorporate more structured educational and learning components, especially for the healthcare staff (medical, nursing, allied health personnel).

One of the initial steps which was undertaken was to define our M and M rounds. Some synonyms for the term would be M and M conferences as well as M and M meetings. Our definition needed to be sharp and clear yet all-encompassing, reflecting the task to be undertaken and achieved (Table 1). Thus we defined it thus: A gathering of inter-professional healthcare team whereby patient care issues and case studies are discussed with a forward view of learning and enhancing quality of care. It is a platform to examine and analyze in a non-judgmental way, adverse events, serious reportable events, errors and near misses and their impact, if any, on patient care and outcomes. It should offer educational opportunities to pick up good practices to enhance patient safety and quality from the perspectives of human factors as well as systems factors. The principle that guides the planning is the need to have a safe, open and respectful environment for discussion of the relevant cases, with an educational objective for all. In order to revamp and change the M & M format and process, it was necessary to get the buy in the head of department, senior nursing colleagues and faculty. The objective was to make the M & M rounds a platform for enhanced, effective and efficient learning, for all groups of staff in the ED. It was also important to identify champions for the proposed change. As the Director of Quality and Clinical Service, the author was definitely one to lead the way. A deputy was also appointed. A few nursing managers were also engaged and empowered to help with the process. Following this, a simple needs assessment and focused feedback gathering was carried out. These were mostly verbal inputs and small focused group feedback, obtained during roll-call for nurses, senior staff meetings and other informal channels. A proactive literature review was also conducted, hoping to learn some of the best practices from around the world (Table 1) [6,8,9-16].

Some of the inputs obtained included that the M & M sessions were very routine and long, going through the list of cases and patients. Some were repetitive and the discussions lack depth, with some faculty giving their ad hoc views and comments. Many of the nursing colleagues felt they lacked participation during these sessions. Others felt these sessions were alright as they were and we could continue as status quo. There were a couple of faculty who stated only the “coroner-referred cases” should be discussed and the follow up actions needed to have some concrete targets set. The majority of those interviewed felt that the discussion on the Serious Reportable Events (SREs) should be maintained. There was also a comment of enhancing the element of psychological safety for those involved in managing the cases put up for discussion.

The feedback obtained will be influenced by multiple factors such as seniority, the level of training, medical versus nursing staff inputs etc. Some of these reflected the main thrust and focus of these groups at this point in their career and life. Residents in general, tended to want more information, content learning and knowledge. This was understandable as they were at the stage of preparing for various examinations and high stakes assessment. We observed this and termed this as:

Direct Learning: Learning, where the focus is more on acquisition of knowledge, facts and content. These were probably the more explicit information and the didactic portions of the M and M discussions.

The other type of learning comes under:

Indirect Learning: This can in fact be more important than content knowledge and may not even be available from text books. It is a focus on sharing from experiential learning and will arise from the rich and deep discussions as well as the comments made pertaining to the cases put forth for discussion during M and M rounds. These can involve other topics such as patient safety issues, self-directed learning, quality indicators, team culture and so on. This will reflect the departmental culture and practices. Close observations will also be able to showcase the degree of psychological safety the staff possess during such open discussions. It is also a platform for team learning. Other elements include communications, interaction between different levels of staff, competencies acknowledgement as well as addressing and learning the emotional aspects of the work that is done.

The New M and M Model (Tables 2,3) with the definition and all the inputs in mind, we proposed a new model for the M and M sessions. The objectives were set, with a strong emphasis on learning, especially as we wanted to enhance the educational experience during these sessions (Table 2).

The frequency remained monthly. During this M and M rebranding process it was always borne in mind that:

The first change was the implementation of a pre-M and M rounds review session. During this session, which is conducted about one week prior to the actual M and M rounds, a review of all the mortality cases for that month is carried out. The morbidity cases that had surfaced were also reviewed to understand the issues and select the ones for presentation. The people in this review committee include several Emergency Medicine senior faculty, junior faculty, nursing managers and a few senior staff nurses. Each committee member present will review the clinical notes and then complete a template and make a decision on each case.

After member’s present have reviewed all the cases for that month, an open discussion was carried out, whereby each one can bring up any concerns and queries. Questions considered by the committee members would be:

Any Adverse events (complication caused by medical management)?

Based on the responses and discussion, a few cases would be selected for presentation at M and M rounds. The lessons embedded and educational focus must be highlighted clearly in preparing the presentation for the selected cases. Factors contributing to the adverse events or incidents are categorized as follows:

A resident would be selected to present, supervised and guided by an appointed faculty. The resident and faculty selected are not the ones who managed the patient in the ED. This way, there was no need to go through all the cases at M and M rounds but yet they would all have been peer-reviewed at this pre- M and M committee meeting. This also allowed the actual M and M rounds to be curated in a more concise, targeted manner with the educational goals in mind. The presentation itself would follow a guided template and would cover the following: (Table 3).

The thrust of the presentation and sharing would be to help improve patient care and maximize the learning together (team learning) aspect of the shared experience. The staff involved in the management of these patients will also be present at the M and M rounds and they are free to contribute and share if they wish. Learning from errors through reflection and peer- discussions as these are very useful to help improve practice [9,14].

For specific cases such as Serious Reportable Events (SREs), a root cause analysis would have to be carried out involving parties managing the patient. After the M and M rounds discussion, some of these may be put into guidelines or framework if the department deems it necessary, or spin-off projects or quality initiatives may be carried out. This will help to ‘close the loop’ by translating what is educational during the M and M rounds into worthwhile quality and clinical service projects.

With the new M and M model it was decided that two new elements will be incorporated:

Discussion

Generally defined, ethics is about what is right or wrong, or what is worthy of praise or blame. This is a very gross definition. In considering ethics associated with clinical patients, decision making related to care and other issues, there are indeed more complex factors and issues to be taken into account [15,17-19].

Every patient contact has ethical element/s attached to it. There may be dilemmas that arise, especially in the management of complex cases, time dependent cases management and other more general ethical principles. Besides emphasizing clinical reasoning, discussion of the ethical aspects of the ED cases aims to strengthen ethical reasoning of residents by educating them to recognize ethical tensions, the increased resources needed for dealing with these tensions, the promotion of open and nonjudgmental discussions, especially involving complex cases and families. The multipronged objectives for the ethics discussion are summarized in Table 4. The inculcation of these sessions is also to enable more staff to see the “ethics in every case” and realize how important this aspect of the management is. It also will help create awareness of the ethically important moments in the ED patient contact. The introduction of the segment in to the M and M rounds is hoped to enable us to develop a common and more universal language when discussing ethical issues and cases. It will provide a platform to learn best ethical practice and at the same time provide some opportunities for ethics debrief [17-19]

Some examples commonly seen in the ED, which can be highlighted for teaching purposes would include:

Besides some of these examples, there are also issues such as collegiality, respect, inter-professional practice and maintenance of confidentiality, which also encompass elements of ethics. Thus ethics is embedded in multiple context and circumstances than often than we realize.

Human Factors Segment at M and M Rounds

Human factors elements and consideration are extremely relevant and critical in Emergency Medicine in view of its extremely dynamic, fast-paced and complex environment. There are multifaceted discussions, interactions and processes at various points and junctures. Due to this, lapses, errors and oversight can happen at many more potential points [20-25]. Thus, it is necessary to create the awareness, as well as have frequent reminders on the importance of human factors elements. In the M and M rounds, short, 10-minute Human Factor sharing will be conducted every other month (alternating with the Ethics Discussion). The topics to be covered include those in the Table below. We also managed to secure a Human Factors Specialist to come in to help coordinate and run these short segments, at no additional cost.

Even as we have just commenced this new model, the Ethics and Human factors segments have garnered much positive feedback and interest and we will continue to develop these over the months to ensure a robust discussion. These topics also help create the awareness of a more wholesome approach to our work in the ED and help make staff more conscious of these aspects of work [27].

The process of review and rebranding of the M and M rounds is very much a process of transformative learning. Certain observations and assumptions were present with the current model. Then there was the recognition of these and realization of the need to transform or change. The options were then explored with collaborative inputs from all levels of staff. This is followed by the new model and proposal which needed to be put into action, securing the appropriate resources. All these are done with the hope of enhancing learning, deepening the learning and understanding of our staff, as well as building up their competencies and confidence. It is also about team and departmental learning, beyond just individual learning. Learning together requires an open mindset and the ability to learn, unlearn and relearn. At the same time, open sharing, non-blaming culture and psychological safety elements are integrated [28,29].

Conclusion

The emphasis on educational enhancement as well as sharing best practices, collaborative care, strong foundations of clinical reasoning and decision making process in our healthcare staff is crucial. The majority of them will stay in their careers for many years to come and continue to develop and add further to their spectrum of experiences. Adverse events and errors can certainly cause significant emotional distress. Often, due to the hectic pace of the work, there may not be much time to ponder over such incidences and the psychological impact can be easily overlooked. Thus it becomes important to highlight to our healthcare staff the importance of these. Supervisors, faculty and heads of department can help reinforce this and help with providing support and facilitated interviews or debrief. Discussing these issues openly can help staff be more aware and feel more psychologically safe in talking about` it more openly. In changing we do have to overcome challenges and cross boundaries (physical, psychological and departmental). It may take effort and time but the results and outcomes are worth it all.

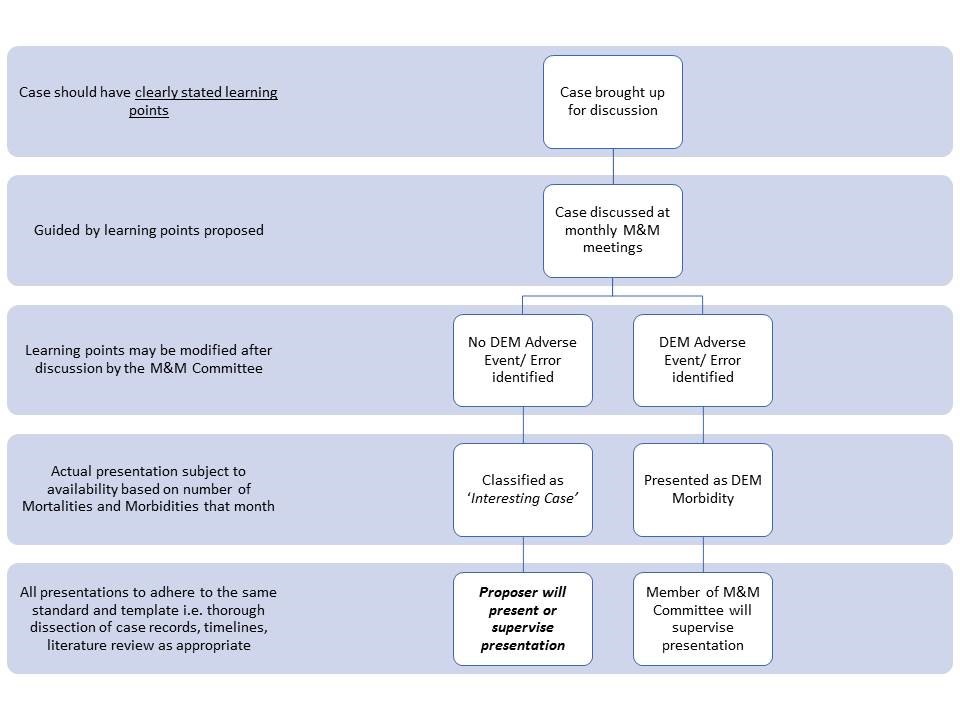

Table 3: The New M and M Model (DEM: refers to Dept of Emergency Medicine).

|

1. |

To have a definition of M and M, which aligns objectives |

|

2. |

Review of the current M and M format. Sieve out the good practices to retain |

|

3. |

Feedback (focused group, verbal, ad hoc) and Analysis |

|

4. |

Needs assessment (from various stakeholders) |

|

5. |

Review of literature for best practices and updated information |

Table 1: Steps in the Re-organization of the M and M.

|

1. |

To focus on learning and improvement of systems/ processes of care |

|

2. |

To promote detailed analysis and understanding of cases, with a view to inculcate deeper learning. This is tagged to strengthening clinical reasoning and reflective practice |

|

3. |

To promote a condusive and stimulating learning environment, with an emphasis on psychological safety |

|

4. |

To encourage team/ departmental learning and inter-professional learning |

Table 2: Objectives of the New Model M and M Rounds.

|

Fatique Interruptions (26) Mental Model Perceptual Grouping Working memory Long term memory Teamwork Communications, closed loop communications Verbal and non-verbal communications skills Visual search Speaking up Automatic skills Just Culture Affordance in desig |

Citation: Fatimah L (2019) Enhancing the Educational Experience of Mortality and Morbidity (M & M) Rounds in the Emergency Department (ED). Emerg Med Trauma Care J: EMTCJ-100013.