Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecological Problems

(ISSN 2652-466X)

Research Article

Knowledge of Gynecologists during the Care of Women Victims of Violence in the Public Brazilian Health System

Albuquerque Maranhão DD*¹, Franco Ramos GG¹, Galfano GS¹ and Troster EJ¹

Department Maternal-Infant, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brasil

*Corresponding author: Débora Davalos Albuquerque Maranhão, Department Maternal-Infant, Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein, São Paulo, Brasil

Citation: Albuquerque Maranhão DD, Franco Ramos GG, Galfano GS, Troster EJ (2021) Knowledge of Gynecologists during the Care of Women Victims of Violence in the Public Brazilian Health System. J Obstet Gynecol Probl: JOGP 100023

Received date: 03 March, 2021; Accepted date: 15 March, 2021; Published date: 22 March, 2021

Abstract

One of every three women will suffer violence during her life. Characteristics of this type of violence are from a historical process and specific culture that generates prejudices to all the society. Health professionals, especially obstetricis and gynecologists (OB/GYN) are important entrance doors to provide the first care for these victims and they must be prepared to provide the adequate care. Objective: To evaluate the knowledge of OB/GYN in care for women victims of violence in the public health system and the existence of institutional mechanisms to support, and develop a protocol for this care. Material and methods: This was a cross-sectional and observational study with application of an electronic questionnaire and OB/GYN who conducted care of emergency unit in the public health system. Our goal was to identify the care delivery for violence victims, institutional mechanisms of support, difficulties to find in the care and estimations of prevalence of violence against women. Results: A total of 92 physicians responded the questionnaire. Of these, 85% had already provided care to any case of violence, 60% believed that less than 20% of women received adequate care in these cases, due to mainly the short time for consultation, unprepared team, and lack of institutional resources. A total 61% of participants believed they were not prepared to conduct adequate care and those who made us to believe on their success mainly in the existence of institutional support. Conclusion: The most of interviewed physicians, although reported they not have the knowledge of conduct adequate care to victims of violence, however they did not provide such care due to the lack of institutional support. A protocol of care with assertive actions can help the team to provide the best care for these cases.

Keywords: Domestic violence; Gynecology intimate partner violence; Medical care; Sex offenses; Violence against women

Introduction

Sexual, domestic and intimate partner violence against woman are a global public concern, given that one in each three women will face violence in their life [1,2]. In 2016, 4,645 women were assassinated in Brazil, and the rate of homicides for each 100,000 Brazilians is 4.5. This type of violence had an increase of 6.4% in the last 10 years [3]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), almost one third (30%) of all women in a relationship had suffered physical and/or sexual violence by their intimal partners who are also responsible for 38.6% of women homicides around the world [2,4].

The concept of violence against women must be understood as a relationship of inequality of power, which is a form of historical process and sociocultural subordination of women to men, who expose specific situations linked to violence that are directly related to gender [5]. Their specific characteristics include: be the main offending agent (70 to 90% of cases worldwide) a man, the intimate partner, someone who is trustable, from the family or affectively linked to the victim. The violence occurs in most of times in domestic environment and not in public, and they present high proportion of sexual violence among those who suffered violence (265 in women against 6.1% in men in the municipality of São Paulo) [6].

In addition to be a violation of human rights, to inflict violence against women causes immediate outcomes and in a long term period to the populational health including: physical traumatisms, unintended pregnancy, miscarriage, gynecologic complications, transmission of infectious diseases, and mental disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorders and depression [7,8]. In addition to the high risk factors, such as smoking and abuse of alcohol and drugs that are significantly most frequent among victims [8,9].

Currently, prevention strategies are still scarce and only a few has scientific evidences of efficacy: education at schools [9]. Other strategies such as micro-funding programs for women, education on gender equality, reduction of access to alcohol, and campaign for changes of accepted social-cultural norms of passivity to the violence are also efficient actions [1].

However, these actions are most of times specific and they could not avoid severe outcomes given that women are included in the recurrent cycles of violence, and they need a structured support in order to escape from new aggressions [10].

In Brazil, the Maria da Penha Law (Law n? 11.340/2006), in addition to establish mechanisms to penalize assaulters, we sought to treat in an integrative manner the phenomena of domestic violence [11]. By this law, we created social assistance instruments to seek for life alternatives for these women, protection, and emergencial embracemente, theoretically stated in health and public security systems [12].

In order to fulfil the law it is fundamental to maintain, amplify and enhance these supportive network for women, such as access to health system given that in many cases they seek a number of times for this service before seek for the police or specialized court and, therefore, supportive services constitute one of the main entrance doors to embrace and notify occurrences [9,13].

In 2016, whereas the Brazilian policy reported 49,497 rape cases, the public system recorded 22,918. Undoubtedly, these two databases have a large under notification and they are unable to clarify the extension of the problem. In the United States, only 15% of rapes are reported to the policy. If the Brazilian under notification rate was similar to American, we would be considering a prevalence of rape between 300 and 500 thousand cases/year [3].

Since 2011 the declaration n?104 of the Ministry of Health was established as mandatory the compulsory notification of any identified or reported case of domestic and sexual violence [14]. Between 2011 and 2016, we observed an increase in notification of cases of violence and rape, from 155.1% and 90.2%, respectively. These number are clear examples the positive effects of establishment of compulsory notification [3].

Health professionals, however, face a number of difficulties and limitations to notify cases, such as how to recognize victims, approach and screen patients, and manage them within the hospital. Other limitations are the lack of knowledge about the need of notification, time to complete long forms, and challenges to obtain and forward these documents within institution [15, 16].

In a study conducted by the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada including gynecologists, 33% of them responded that they never or rarely have conducted a screening to identify domestic violence, and 94% of them never had a protocol for screening such victims and the same percentage of participants believe that they done so inadequately [17].

National and international studies in bioethics point out greater difficulties to delivery this care that is physician-centered and includes values judgments about victims, lack of training for professionals, invisibility of cases giving the lack of active questioning; and according to inefficient public supportive network in secondary referrals to continue to provide care for these patients after first care conducted by health professionals [18,19].

Gynecologist is often responsible for the first care of these victims when they are admitted in the health system(20), and for this reason, this is paramount for them to be have the skills to conduct an adequate embracement and effective referral of these patients.

Few studies on the topic had specifically approached this category of professionals and, the studies conducted so far have showed a lack of knowledge of gynecologists and obstetricians regarding identification of cases and their management, in addition studies have pointed out the lacking of institutional support received by them.

Primary objective: To evaluate the knowledge of gynecologists and obstetricians to provide care for women victims of violence at public health system and existence of institutional mechanisms available to support and provide care.

Secondary objective: To develop a protocol for screening and referral in emergency room of gynecologist and obstetricians for cases of suspicion or confirmation of domestic/intimate partner violence, and violence against woman.

Materials and methods

Design of the study and studied population: This was a cross-sectional and descriptive study conducted through the application of electronic questionnaire (appendix 1) the physicians who provided emergency care for gynecology and obstetrics at public health system regardless of the hospital.

Methodology: Participants were recruited via social media through WhatsApp’s groups. The groups were selected by convenience that were included on the list transmission are composed only by gynecologists and obstetricians who attended in the gynecological emergency care, as exposed as follow:

An electronic invitation was send to the groups who agreed to participate in the study. In the beginning of the questionnaire, we applied the inclusion criteria of the study and after data collection the exclusion criteria described below:

Questions were created by the own authors using as the basis a questionnaire applied to physicians working with pre-natal care in the study by [17] that was adapted to the daily care in the emergency room. We included questionnaires on difficulties found by health professionals to provide care for victims of violence, pointed out by other published studies in the literature [18-25]. In addition, other topics included was the need of compulsory notification, and the definition of domestic violence according to the Brazilian law [11].

The questionnaire was validated using a pilot project including 8 physicians who followed the same inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the end, the open field was added for suggestions and critiques used in the re-elaboration of the final questionnaire.

The first two question were applied to verify inclusion and exclusion criteria of the investigation. Both question 1 (Profession: physician) and question 2 (“Are you providing care at gynecologic and obstetric emergency unit at the public health system?) a negative response guided the participant directly to a screen thanking the participation.

Questions include topics about the existence of institutional mechanisms for screening, education and management of cases, support provided by hospitals, difficulties found in conversations with the patient, possible factors that would help to provide the best care for victims of violence, and general notions of the care for the first consultation.

We also evaluated some subjective issues such as percentage of women who suffered domestic violence at any point of their lives; estimation of patients victims among those assisted at gynecologic and obstetric (GO) emergency unit, and if these professionals would believe to be conducting an adequate care for this population.

After gathering of collected data, we conducted a new review in the literature to create an objective and direct protocol for the care of patients victims of the violence at emergency unit in obstetrics and gynecology. We sought to highlight the importance of compulsory notification, screening concerning the type of violence suffered, humanized approach and segment concern the medical, social, and psychological needs of patients.

Main references used as theoretical support to create the protocol were “Preventing intimate partner and sexual violence against women: taking action and generating evidence” by the World Health Organization [23]; the scale “Ongoing Violence Assessment Tool-OVAT” [24]; Módulo II-“Manual de atendimento as Vítimas de Violência na Rede de Saúde Pública do DF” [25]; “Manual de Procedimentos Operacionais para o atendimento Das Vítimas de Violência Sexual” of the Hospital Vila Nova Cachoeirinha [26]; and the papers “How health professional assist women experiencing violence? a triangulated data analysis”, by Mariana Hasse [27], and “Intimate partner violence: diagnosis and screening” by Amy Weil [28].

Ethical aspects

This project was approved by the Ethical Committee for research involving humans, CAAE n. 14503519.7.0000.0071. The consent form was made available on the first page of the eletronic questionnarie and it should be marked as “I agree” in order to the participant to begin to answer the questions. Confidentiality and identify of the participants who responded the questionnarie were guaranteed.

Statistics: No formal calculation of the size of the sample was conducted due to the essentially descriptive charactericts of the research. However, the number of participants were recruited by a convenience sample. Categorical variable were described by absolute frequencies and relatives, and number of variables using mean and quartiles, in addition to minimal and maximal values [21]. To investigate associations between questions with categorical responses using the chi-squared or the Fisher´s exact tests, and groups of interest were compared in relation to estimations of percentages by the Mann-Whitney non-parametric tests. Analyses were conducted with support of the statistic package SPSS, and fixed significance level by 5% [21].

Results

Of 860 physician to whom the invitation was sent to participate in the research (already excluding those participating of more than one group simultaneously), 104 responded the questionnaire and 12 met the exclusion criteria. Therefore, the final sample of this study included 92 responses for the analysis of results. The majority of participants were women (83.7%) and 71.7% of questionnaires were responded by physicians up to 30 years of age, in which almost half of them were medical residents (47.8%), 15.2% had concluded the medical residency, and 37% had title of specialist in obstetrics and gynecology. Of this total, 69.6% also provide care at private health services.

Among included professionals, 89.1% already have assisted a case of violence against women, however, 30.4% of physicians reported the inexistence of at their working institutional of any protocol for the care for victims of violence. In addition, concerning actions by the hospital for sensibility and/or training of professionals to identify and assist these patients, 44.6% responded that the same were not conducted, and 37% did not know the existence or inexistence of this type of action within their institution. Of the 18.5% who responded “yes” to this question, 53% never have participated in the actions, and 21% did not know how actions were conducted.

Concerning the experience of any situation of violence, 47 of the 92 professionals already had experienced any situation closed to them, and 23 responded that this occurred with friends, 13 with Family members, 20 with unknown individuals on the streets, and 12 with themselves. More than 90% of professionals estimated that a number higher or equal to 20% of all adult women had suffered domestic violence at any time of their life, and 51.4% of participants though this number is greater or equal to 40%.

Sings that drawn more the attention of professionals to the possibility of a patient be victim of violence are: symptoms or physical sings of aggression (92.4%), non-compatible history with presented symptoms (88%), referral of having “problems at home or with partners” (82.6%), report of having already suffered violence in the pass (73.9%), introverted patient, quiet, and with distant during the consultation (69.6%), crying patient (59.8%), and patient who refers to have an addiction (drugs, alcohol, smoking, medicines) (41.3%).

In relation to the approach of the patient, 80,4% of professionals reported having an important help from the multidisciplinary team. Only 59.8% of respondents reported that they talked with the patient about the importance of seeking help from families and friends. Only 4 respondents reported that they considered only the current complaint and did not approach the subject of violence. Based on the suspicion of case of violence, 63% of professionals discuss the subject with the patient, 16% discuss only if the patient reports violence, and 19.5% discuss only to discard something severe.

On management measures to be taken, more than 80% of professionals mentioned: privacy guarantee and establishment of an embracement environment; contraception and disease prevention; referral to violence service after the initial care; activity of institutional protocol (existing case); detailed completeness of medical record; and care along with the multidisciplinary team. No professionals marked as a conduct to report the police or mandatory forensic medical examination.

A total of 94.6% of these professional believed that less than half of patients’ victim of violence received adequate assistance in the emergency unit in obstetrics and gynecology. Main difficulties mentioned by at least half of the physicians were: unprepared multidisciplinary team; short time (more than 70% of physicians reported to do a consultation within 10 and 15 minutes); lack of resources to help adequately women victims of abuse; unknown of what resources were available; and unknown of which questions to make, or how to express them. A total of 27.2% of participants reported to feel uncomfortable to discuss the subject, and only four professionals responded not to present difficulties on this care.

All professionals responded to consider important the existence of an institutional protocol for violence cases in which they would be propensity to follow. Measures mentioned as more important to implement this protocol were: to be diffused among all professionals in the area (76.1%); to be fast and easy to access (73.9%); to enable an integrated follow-up with the specialized support team and the multidisciplinary team (64.1%); to reduce bureaucracies (56.5%); and to conduct mandatory trainings (39.1%).

Among general questions view of the care delivered, 58.7% believed that they were not to providing the adequate care for patients victims of violence. Among this believe to conduct adequate care, 46.7% point out as main contributing factor the institutional support, 24.4% to professional experience, 13.3% to classes, and educative material, and 6.7% experience of private life, and 8.9% other factors.

In a comparative analysis among questions, we could perceive that the existence of institutional protocols led to professionals to feel more confidence in delivery care (question 19). Although there is a tendency to improve quality in care (evaluated by questions 11 and 12) to be the best factor between health professionals who work at institutions where there are protocols and that having participated in training and sensibilizing action, there was not statistical significance of this association (Table 1).

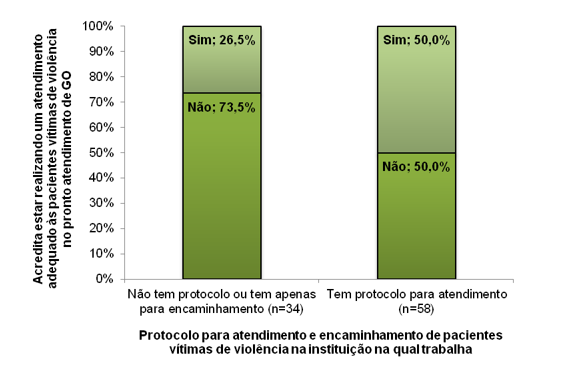

Half of professionals who worked at institutions in which there is protocol believe that they are conducting an appropriate care for patients, against only 26.5% of professionals at hospital in which there is no protocols or where there are only referral protocol, and this relation is statistically significant (p=0.027) (Table 2) (Figure 1).

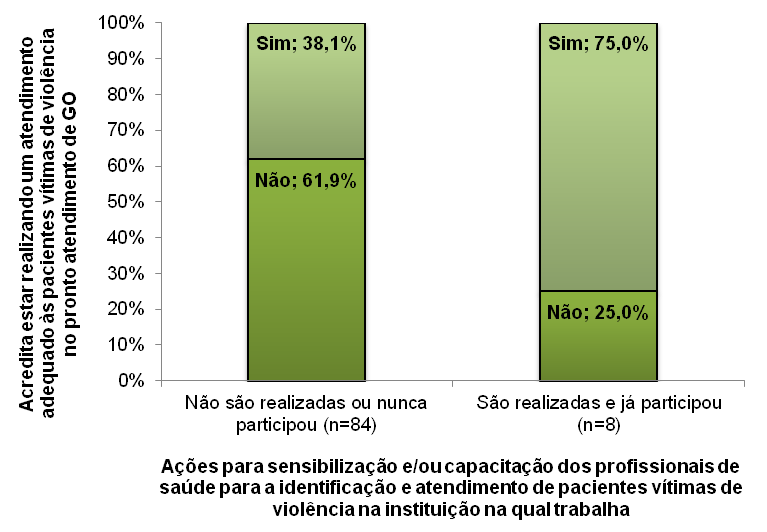

Although there are no statistically significant relationship between these factors (p=0.061), the percentage of professionals that believed to conduct an adequate care to patients was 75.0% among participants of sensibilizingsensitizing and/or training actions promoted by their institution, and this perception was significantly higher than in groups who participated or worked at institutions where there was or lack information about the existence of any type of actions (38.1%) (Figure 2) (Table 2).

We also analuzed the relationship between previous care by professionals to case of violence and percentage of patients victims of violence who were estimated to receive adequate care when they were admitted to emergency unit in obstetrics and gynecology, however, they did not find relationship with statistical significance. Among professionals who reported previous experience with violence situation in an enviromental closed to them, we could not observed statistically significance in comparsion with higher estimative of percentage of adult women who experienced domestic violence at any time of their lives.

Discussion

As the main findings of our study, we observed that obstetricians and gynecologists know how to conduct adequate care to victims of violence and their importance, however, we suggest that the main cause for difficult in care of these patients would be the lack of institutional support, as well as a standardized care protocol and multidisciplinary team trained to delivery this type of care.

Approximately 90% of participants already had provided care to any case of violence against women and they believed that in general 20% or more women had already suffered any type of violence. Such perception agrees with data from the WHO [2] that ratified the relevance of cases of domestic violence in our society and the importance of the subject in public health, directly related to day-to-day of health professionals.

Main sings that drawed the attention of professionals for the possibility of patient to be victims of violence are in agreement with those reported in published literature and they are: symptoms or physical symptoms of aggression, non-compatible history with presented symptoms, mention to have “problems at home or with a partner” report that already have suffered addictions, all situations that are compatible with risk factors approached in the WHO handbook of injury and violence prevention [23]. However, our sample evidenced a higher knowledge of general physicians studies in the literature, the study by Souza A. A. C, a review of 16 articles about care for victims of violence showed that 8 of them pointed out the lack of adequate training in medical education as one the main barriers for adequate care [18], lack of knowledge was also described by a Canadian study that included prenatal care physicians [17].

Concerning the approach to the patient, participants of the study showed to be concerned to seek help of the multidisciplinary team and family support, fundamental points proposed by protocols of Ministry of Health and Federation of Gynecology of State of São Paulo [25, 29], showing more than one adequate performance. Only 4 physicians reported that they are limited to the main complaint of the patient and did not investigate to the supposed violence, a data highly presented in a number of articles by Hasse, M. and Vieira E. M. with percentage of 8.2% of physician performing inadequate approaches [27].

Almost all interviewed professionals (94.6%) believed that less than half of patients victims of violence received adequate care at the emergency unit in obstetrics and gynecology, and the main difficult found are: unprepared multidisciplinary team, little time available for consultation, lack of adequate resources and lack of knowledge about which questions to make or how to express them. An Australian study approached violence by intimal partner in emergency services also pointed out that these difficulties are associated with challenge to keep a non-judging posture and not mixing care with their own sentiments, particularly among professionals who had experienced the violence [30].

The mean care in emergency unit is around 10 to 15 minutes per consultation, a time that although agrees with the published literature for care in emergency unit in obstetrics and gynecology (colocar referência), sometimes is not enough for depth approach of such sensitive subject and may not be covered in the main complaint of patient, because of this there is need to identify the risky case and provide a higher time for the consultation of such patients.

Of interviewees, 30.4 of physicians responded that where they work did not have any protocol for caring of victims of violence, however, all professionals responded about the importance of the existence of an institutional protocol for care and referral of patients, and they would be likely to follow them, being unanimous their importance. The protocol of prevention to sexual violence and by intimate partner against the woman of the WHO affirm the importance of existing institutional protocol to facilitate and enable an adequate care to victims of violence , in which pointed out issues for direct approach and means to referral of the case [23].

Based on mentioned measures by the physicians as the most important to implement one institutional protocol, such as: to be well-diffused between all area of professionals, to be fast and easy to access and enable an integrative follow-up with specialized support team and multidisciplinary team; we created a directed protocol with closed and objective questions; with the aim to homogenize the gynecologic care and cover inclusion of multidisciplinary team, the goal is to conduct adequate care to this patient and to health professionals to feel more safety to provide care for victims, and therefore to avoid underdiagnosed and severe outcomes.

Our protocol (appendix 1) was created to help to identify possible victims through specific characteristics that must be observed [31]. After that, to direct the approach of the same through direct questions based on protocols already existing [32] such as Ongoing Violence Assessment Tool (OVAT) [24] and screening of ACOG of violence by intimal partner [33] available in direct form to dispense of a short time for medical consultation, in addition to complement the multidisciplinary team, which enable in the conduction of the case. In addition to point out questions to conduct and behave for assessment that avoid judgments and leave the patient more confortable to report their history [19, 26]

After identifying and approaching the victim, the protocol also direct the diagnosis, the conduction [34] and improved approach to be done with the patient, all based on protocol of the Ministry of Health in Brazil and ending with some point of law support that can be accessed in the city of Sao Paulo [29, 35,36].

Concerning limitations of the study, due to the descriptive and observational methodology we could not infer that knowledge showed by physicians would be also really applied in the daily practice. We also due to questionnaire must be self-applied and can have occurred a bias of selection of those physicians with higher interest and knowledge on the subject.

Other difficult found was the evaluation of institutional resources, which were only questioned and was not verified directly with institutions, therefore, what was obtained was the partial view, reported by part of physicians about really existed. In addition, we obtained a small sample (92 interviewed included) and physicians who worked in the city Sao Paulo, not being representative of all population of physicians who attended in public health system around the country.

Next steps in the study on physician care and the violence against women that could approach the patient´s view in relation to the professional care and approach. Questioning how victims felt in the consultation, what lacks in viewing of them to improve the approach and follow-up, in a form that they feel more comfortable to open and report violence episodes.

Conclusion

We identified that most of interviewed physicians recognized the importance and have the knowledge of identifying and conduct an adequate care the victims of violence. However, the majority found difficult in conduct an adequate care due to the unprepared multidisciplinary team, to restricted time for care, the fact of not having adequate resources and mainly by lack of institutional support to guide assistance in a better care for women victims of abuse.

Considering the importance of the existence of an institutional protocol that can guide and orient the direct care and adequate embracement for these patients, we create a protocol that after identifying and approach victims, this directs the diagnosis, the management and improve approach to be done with the patient. We believed to be fundamental to turn the hospital not only a source of treatment, but also the place for embracement, prevention, and notification of this type of aggressiveness, therefore, we sought to include in this protocol issues of embracement at the emergency care unit.

Figure 1: Relationship between institutional protocol and adequate care delivery by physicians participating in the study to patients who were victims of violence

Figure 2: Relationship between institutional actions and adequate care delivery by physicians participating in the study to patients who were victims of violence

|

Institutional support |

Medical care delivery to patients with suspicion of violence against women |

p value |

|

|

Incomplete or adequate |

Incomplete or inadequate |

||

|

Protocol for care and referrals of patients victims of violence |

- |

- |

0.484 # |

|

There are no protocols or there are only for referrals protocols (n=34) |

23 (67.6%) |

11 (32.4%) |

- |

|

Protocol for caring (n=58) |

35 (60.3%) |

23 (39.7%) |

- |

|

Actions for sensibilizing and/or training of health professionals to identify and delivery care for patients who are victims of violence* |

- |

- |

0.705 $ |

|

They are not conducted or they do not whether they are conducted, but never participated (n=84) |

- |

- |

- |

|

They are conducted and already participate (n=8) |

6 (75.0%) |

2 (25.0%) |

- |

|

Note: #: Chi-squared test; $: Fisher exact test; *: any type of violence |

|||

Table 1: Association between institutional support and medical care delivery by gynecologist who participated in the study to patients with suspicion of violence against women.

|

Institutional support |

I believed that an adequate care was provided to patients who were victims of violence at emergency unit of obstetrics and gynecology |

p value |

|

|

No |

Yes |

||

|

Protocol for care and referrals of patients victims of violence |

|

|

0.027 # |

|

There are no protocols or there are only for referrals protocols (n=34) |

25 (73,5%) |

9 (26,5%) |

|

|

There is caring protocol (n=58) |

29 (50,0%) |

29 (50,0%) |

|

|

Actions for sensibilizing and/or training of health professionals to identify and delivery care for patients who are victims of violence * |

- |

- |

0.061$ |

|

They are not conducted or they do not whether they are conducted, but never participated (n=84) |

52 (61,9%) |

32 (38,1%) |

- |

|

They are conducted and already participate (n=8) |

2 (25,0%) |

6 (75,0%) |

- |

|

Note: #: Chi-squared test; $: Fisher exact test; *: any type of violence |

|||

Tabela 2: Association between institutional support and adequate medical care delivery by gynecologist who participated in the study to patients with suspicion of violence against women

Citation: Albuquerque Maranhão DD, Franco Ramos GG, Galfano GS, Troster EJ (2021) Knowledge of Gynecologists during the Care of Women Victims of Violence in the Public Brazilian Health System. J Obstet Gynecol Probl: JOGP 100023