Australian Journal of Nursing Research

(ISSN 2652-9386)

Research Article

Drug Addiction and Crime: Prevention Begins in Schools

Vitale E1*, Della Pietà C2, Agresti R3, Lacatena C4, Gualano A5 and Germini F6

1Department of Mental Health, Local Health Authority Bari, Italy

2Manager of Health Professions, Local Health Authority Bari, Italy

3Nursing student at the University of Bari, Italy

4Coordinator of the Degree Course in Nursing, University of Bari, Taranto headquarters, Italy

5Nurse coordinator of Urology ward; SS. Anunziata Hospital, Local Health Authority Taranto, Italy

6Manager of Health Professions, Local Health Authority Bari, Italy

*Corresponding author: Elsa Vitale, Department of Mental Health, Local Healthcare Company Bari, Italy

Citation: Vitale E, Della Pietà C, Agresti R, Lacatena C, Gualano A, et al. (2021) Drug Addiction and Crime: Prevention Begins in Schools. Aus J Nursing Res AJNR-100024

Received date: 05 January, 2021; Accepted date: 18 January, 2021; Published date: 25 January, 2021

Abstract

This study provides an analysis on the world of crime related to drugs and drug addiction in a youth context but above all to emphasize how much school can be fundamental in the prevention of this task. An ad hoc questionnaire was administered online, aimed at children attending upper secondary school. The questionnaire was answered by 100 children aged between 15 and 19 years. Of these, 59 were female and 41 were male. The responses showed the existence of a high distance between young people attending secondary schools and notions on the world of drugs. Therefore, the environment in which young people are placed on a daily basis would also affect the success of the intervention: the adolescents who participated in the innovative program while maintaining close relationships with peers who took drugs, did not obtain significant benefits.

Keywords: Drug Addiction; Prevention; Schools

Introduction

Drug addiction, the use of drugs among young people and related crimes, are becoming increasingly the subject of discussion as the numbers and statistics of recent years speak of an increase in children who approach the world of drugs without knowing any consequences of their actions. School is one of the most important stages in a person's life and in particular the secondary school, as the children who attend it live a period in which curiosity, the will to feel emotions and the desire to live new experiences can lead to making bad choices [1].

For this reason, this study focuses on the deepening of this topic trying to provide an analysis on the world of crime related to drugs and drug addiction in a youth context but above all to emphasize how much school can be fundamental for young people in the prevention of drugs and related crimes.

Materials and Methods

An ad hoc questionnaire was administered online, aimed at children attending upper secondary school, with the aim of observing their behavior and examining their thinking towards drugs. The questionnaire consists of 26 multiple choice questions to try to find all the necessary information relating to the knowledge of drugs, the difference between soft drugs and hard drugs, the use of drugs, the reason for which they are used, the relationship between school and family, and information on the harm that drugs can cause [2].

Results

The questionnaire was answered by 100 children aged between 15 and 19 years. Of these, 59 were female and 41 were male. Among the most relevant answers:

Discussion

The responses to the questionnaires showed the existence of a high distance between young people attending secondary schools and notions on the world of drugs. The boys are curious but with little information given the fact that drugs are a subject that is not very covered both in the family but especially in schools. Kids are aware of the difference between soft drugs and hard drugs, but too many kids don't know the law regarding drug use. Most of the children declare that it is more important to them to have information from the school than it is to receive it at home. At the same time, it is clear from the answers, in the classroom it is very rare that we talk about drugs with teachers, despite the fact that a good part of the children have seen with their own eyes the use of drugs and even dealing in schools attended [3].

A possible explanation can be provided by the evident lack of schools of a suitable educational organization in dealing with this type of topic, by the problem of staff who are poorly informed on the subject and therefore not suitable for carrying out drug prevention. The school, to be of fundamental help in the prevention of drugs, related risks and related crimes, should be able to provide a fair analysis on the world of drugs and drug addiction through a professional figure in the field of prevention, or the figure of the nurse. One of the main functions of the nurse is the prevention of diseases and with his knowledge and empathic capacity he can be the right figure to be included in schools to solve the problem of drug prevention [4-6].

Prevention is a set of activities, actions and interventions implemented with the primary aim of promoting and maintaining the state of health and avoiding the onset of diseases. The word that gives meaning and connects the terms school and prevention is education. In fact, school and prevention concern education, the act or process by which the acquisition of knowledge and skills is supported and facilitated, the development of the ability to reason and judge, the formation of an autonomous individual, intellectually and emotionally mature for adult life [7-9].

For this reason, a school that works as it should, by definition contributes to preventing the problematic use of psychotropic substances. But a school can truly and truly educate prevention only if what it is and what it does is recognized on a social and political level, if what it teaches is reflected on a social and political level. A school can truly educate and truly do prevention only if education is seen as something that involves the entire system that contributes to educating not only the school, but also the parents, the local community, the production system. Unfortunately, it is evident how far this ideal condition is and even seems unattainable [10].

Within this non-functioning educational system, the school tries to do something specifically dedicated to addiction prevention. Unfortunately, often good intentions, when not accompanied by a solid knowledge of the active ingredients of prevention and scientific evaluations of the effectiveness of the strategies implemented, end up producing effects opposite to those expected. Doing addiction prevention at school can be helpful but you need to be very careful. Among the approaches to prevention that the literature recommends avoiding at school are:

The exploitation of fear: It is understandable why it is commonly believed that prevention can be done by showing the most terrifying consequences of drug abuse. However, research shows that this strategy doesn't work. Terrorism can have a short-term impact on some. It can also have a long-term impact. But this generally concerns precisely those young people who are already not at risk, the less impulsive and less likely to engage in deviant behaviors or in search of strong sensations, excitement. In those most vulnerable to consumption, more impulsive and susceptible to the fascination of deviant behavior, risk and strong feelings, the knowledge of certain adverse effects, especially psychological, can even encourage the desire to explore and consume substances [11].

In general, therefore, frightening is a failure strategy. Young people will tend to read the terrorist message as distorted or unreal information, generally not corresponding to their experience or observation of what happens to others. In fact, although a large proportion of children use some psychoactive substance, including alcohol and tobacco, only a few, fortunately, develop problematic behaviors, addictions or serious physical harm. However, young people tend to respond to these messages with elusive reasoning or speeches such as “this can't happen to me”.

Furthermore, the psychological sciences and neuroscience have amply demonstrated how children live within a very short time horizon, are unable to emotionally and motivationally feel the future, the future consequences of their behavior. Thus, although they may know perfectly well that using a substance is harmful and has negative consequences on their development and their future health, this knowledge fails to translate into an emotional feeling and a motivation not to consume [12].

The invitation to direct confrontation with former drug addicts at school this is another common and understandable strategy, but once again a method that scientific evaluations of effectiveness have shown to be inadequate and sometimes even counterproductive. To summarize the reasons for this ineffectiveness the comment of a fourteen-year-old to one of these witnesses made during a meeting at school: “So if you use drugs you can enjoy the good things they give you and once the bad ones come out you can stop and then get a job that allows you to be an expert and take the stage to talk to people and be seen as someone special. Not bad”.

Active information: The behavior of an individual certainly depends on what he knows and it is right to inform children about the mechanisms of action and the effects of psychoactive substances. Unfortunately, actions are only partly determined by knowledge. All smokers, those who use alcohol and consumers of illicit substances known to a greater or lesser extent the risks they face, but this does not stop them from consuming them. The marginal role of knowledge and information in decisions is even more marked in young people than in adults. In boys, decisions about behaviors to take are more dictated by impulsiveness, the search for immediate gratification, underestimating future consequences and peer pressure.

As with the strategies seen above, this approach can strengthen the attitude of not consuming for those who already have it, but alone it offers little else in terms of improving decision-making skills, self-control, coping with peer pressure to consume. Rather than information on drugs, knowledge on strategies for strengthening self-regulation skills, to improve self-efficacy, for the management of unwanted emotions and stress, to be able to effectively resist the social influence towards consumption would be much more useful [13].

Just say no! To drugs, I say no! A slogan launched by the largest and longest prevention campaign ever carried out in the world, the one launched in 1982 by the Reagan administration in the United States. A concise, memorable and apparently incisive motto. But was it and is it effective? Research done on the outcomes of this campaign and this approach would indicate that the strategy is not working. It can help strengthen the belief not to consume in people who already have a negative attitude towards use. Unfortunately, it does not offer the most vulnerable subjects useful tools to resist the pressures towards consumption or to regulate negative emotions and moods that can favor drug research and use.

Discussion with experts, specialists, law enforcement agencies: Opportunities to meet with experts and specialists at schools can be very interesting, particularly for adults or teachers, but are less likely to be effective for students. First, it usually means sitting passively listening and we know that without active involvement there is no real internalization of learning and therefore it is not possible to obtain prevention. Secondly, with this approach, rather than responding to the questions and needs felt by children, adults impose the transmission of content and perspectives, often wrongly aiming and generally failing to intercept trust and real listening. Thirdly, external specialists and experts are usually not trained and competent in managing educational processes, a job in which teachers are experts. This does not mean that these interventions must be excluded a priori but that they must be carefully studied and organized together as a sign nti and students so that they respond to specific understanding needs and take place with maximum pedagogical efficiency, guided and regulated by the teachers themselves [14].

Furthermore, studies carried out in the past years have shown that "mutual aid" is more effective than traditional programs. Indeed, prevention programs aimed at high-risk adolescents conducted by their peers would allow a reduction in drug use by 15%. It is the result of a study by the University of Southern California - Health Sciences (USC-HS 2007). Many prevention programs disseminate information on the harmful effects of drugs and teach behavioral coping techniques without considering how strong peer influence is at this juncture. Networked prevention can be very effective in achieving long-term behavioral changes in adolescents. The study compared the results obtained from a traditional prevention program conducted by an adult with a version of the same program conducted by adolescents. The use of tobacco, alcohol, marijuana and cocaine has been verified [15,16].

The environment in which young people are placed on a daily basis would also affect the success of the intervention. In fact, the adolescents who participated in the innovative program while maintaining close relationships with peers who took drugs, did not obtain significant benefits.

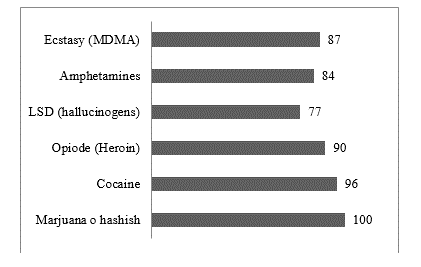

1. What drugs do you know among these listed?

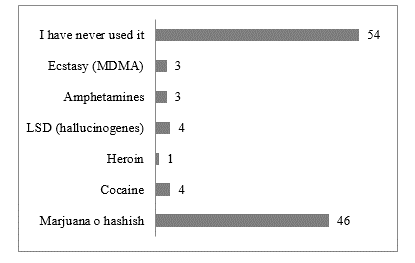

2. Have you ever used drugs? If so, indicate which ones.

The 46 boys who replied that they used drugs said they all used marijuana and hashish.

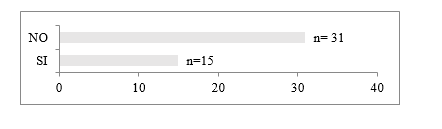

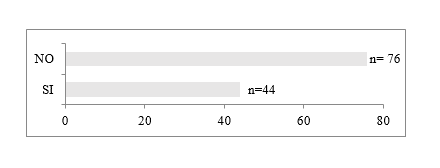

3. Are your parents aware that you have or are using drugs?

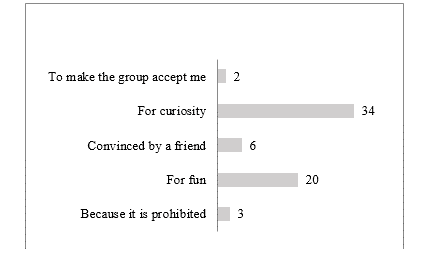

4. Why did you use it the first time? (One or more answers).

5. Are all drugs the same?

6. Do you talk to your parents about drugs at home?

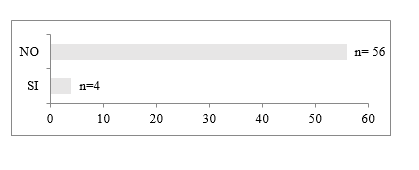

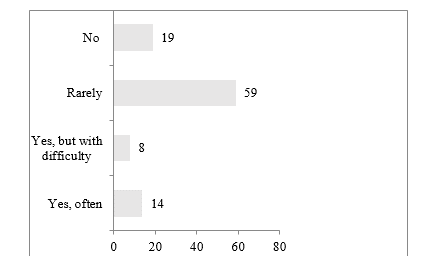

7. Have you ever seen them used in school?

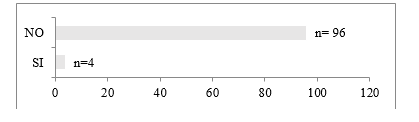

8. Have you ever seen drug dealing in school?

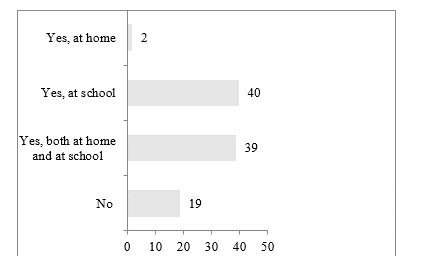

9. Is it important for you to talk about drugs at school?

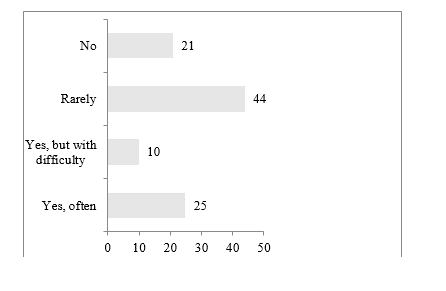

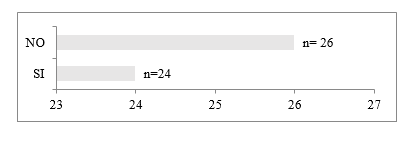

10. Have you ever talked about it at school with teachers?

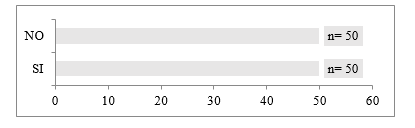

11. Would you like to receive information about the drug and related risks?

12. Do you know what the law provides for drug use?

Citation: Vitale E, Della Pietà C, Agresti R, Lacatena C, Gualano A, et al. (2021) Drug Addiction and Crime: Prevention Begins in Schools. Aus J Nursing Res AJNR-100024