Australian Journal of Nursing Research

Research Article

Cultural Wailing: An Indigenous Experience

Charbonneau-Dahlen B*

Department of Nursing, Minnesota State University, USA

*Corresponding author: Barbara Charbonneau-Dahlen, Department of Nursing, Minnesota State University, USA

Citation: Charbonneau-Dahlen B (2020) Cultural Wailing: An Indigenous Experience. Aus J Nursing Res AJNR-100013

Received date: 04 June, 2020; Accepted date: 08 June, 2020; Published date: 15 June, 2020

Abstract

Among indigenous peoples, the phenomenon of cultural wailing may still manifest in times of intense grief, such as situations of traumatic loss, bereavement, or anxiety-filled events that provoke resurfacing of buried memories. Wailing expressions serve to communicate and frame the reality of traumatic events. In nursing, there is scant literature that documents cultural wailing in response to traumatic loss. In this study, the author offers an indigenous perspectiveofcultural wailing as observedin three cases of unresolved griefstemming frommission boarding school trauma. This was accomplished through secondary analysis of dissertation data, focusing on the types of memories that provoked cultural wailing, the characteristics of the wailing, and what strategies facilitated the transition out of wailing. This study helps demonstrate how the stripping away of culture and identity inflicted during the boarding school era haunts survivors of the events to the present day. The aim is to provide healthcare workers with the background and perspective that can be helpful when accommodating the needs of indigenous peoples who are experiencing trauma.

Keywords: Cultural wailing; Deathand mourning rituals, Health disparities; Historical trauma;Indigenous; Mission boarding school survivors

Introduction

Nurses and other healthcare professionals are called upon to offer support for patients and their families through times of great distress. This can be difficult when confronted with cultural practices that are foreign to the caregivers. It can result in confusion, misunderstanding, and discomfort for those on either side of the dilemma.

Such an occurrence has been documented by [1] in recounting events taking place in an Australian hospital following the death of a beloved community member when a large crowd sought to gather at the bedside of the deceased. Many were crying loudly and wailing, while others, completely engulfed insadness and a sense of great loss, huddled in the narrow corridors. Some were seeking information from the nurses who were taken aback by the unfolding drama and the sheer number of Africans who turned up at the palliative care ward. Many were wailing loudly, which is the accepted way of coping with deeply mournful situations among many cultures worldwide [2]. Although they tried their best to empathize with the community, there was observable frustration on the part of nurses and doctors.It was clear that the health-care system was totally unprepared for such an event and it was difficult for nurses to appropriately handle such mayhem in the ward [3].

The situation described above is becoming more and more common at healthcare facilities around the world as developed nations strive to extend assistance to the influx of immigrants seeking refuge from disaster. There is a call for healthcare professionals to expand practices and policies allowing for compassionate consideration of the needs of persons of diverse cultural backgrounds. Emergent with this expansion of cultural awareness comes the recognition that there are those who have always lived in America–indigenous populationswhose customs and cultural practices have been harshly suppressed. What follows is an examination of the re-emergence of wailing, the cultural expression of mourning as traditionally expressed among indigenous people. Healthcare professionals would benefit from consideration of the healing value of this tradition that they might find ways to be supportive, thereby reaffirming their role as facilitators of healing.

To understand the wailing woman as witness may be a necessary step in coming to terms with trauma and taking the first uncertain steps toward healing.The call of the wailing woman that mobilizes communities to weep together is closely associated with a passion for justice. By taking up this call to lament and by naming tragic events without avoiding the pain, the wailing womenhelp the community move beyond its trauma and so become a powerful symbol of survival in a traumatized world.By bringing people together in their grief, by offering appropriate avenues to voice suffering, and by resisting the powers-that-be responsible for ongoing suffering in the lives of innocent victims, contemporary wailing women may play an important role in helping victims of trauma to heal.

Purpose

The historical perspective of American Indians is necessary in order to understand American Indians today. The author described the mission boarding school experience as a tragic chapter in the longstanding and ongoing saga of aggression, exploitation, and abuse inflicted upon the American Indian people [4]. Enrollment of Native American children in Indian boarding schools was estimated to be around 100,000 [5]. This practice of Indian child removal began in 1869 and continued into the 1970s. Many scholars have documented the cultural genocide that took place in order to acculturate Indian children into the dominant culture. The aftereffects of this injustice continue into the present day.

The purpose of this study was to conduct secondary analysis of an existing data set to document cultural wailing as a wayof communicating traumatic lossfor indigenous individuals; specifically, this study examined wailing among Lakota and Chippewa women who, as children, had been removed from their familiesby the US government and relocated in boarding schools. Historical trauma has resulted in health disparities that persist to the present day.This has resulted in the perpetuation of historical mistrust of health services, health providers, and researchers.

The cultural wailing stories of these women that occurred in three different situations are used to illustrate the significance of culturally relevant expressions of loss. The cultural wailings were observed during resurfacing of memories of mission boarding school experiences. Symbiotic allegory,an indigenous qualitative methodology[1] was utilized together with storytelling method [6] to evoke buried memories of traumatic events experienced by these women during childhood. Symbiotic allegory requires the use of a researcher who has endured similar experiences of the group being examined, and who, therefore, mayconduct research from the basis of a shared bond of knowing, thus facilitating a trusting relationshipthat enables the research participant to unearth events previously unspoken due to their heinous nature. Through the examination of the candid stories of Indian mission boarding school survivors, this research provides a frameworkfor documenting life experiences from a diverse perspective.

Significance

The findings from this research expandsnursing knowledge of culturally appropriate health care practices for indigenous individuals whose lives have been affected by historical trauma[7]. Storytelling methodology as studied by [8] has been expanded to include an indigenous cultural perspective. Information gathering through storytelling methodologyis culturally relevant for individuals who have experienced historical trauma [9] and was verified in Charbonneau-Dahlen’s work using symbiotic allegory with indigenous mission boarding school survivors (2019).

Search Parameters

Interest in wailing as an expression of grief was provoked by the unanticipatedfinding of the existence of the cultural phenomenon of wailing inthe original work on historical trauma of indigenous mission boarding school survivors by the author[1]. Consequently, an exhaustive search was conducted on cultural wailing. Library searches were conducted of conceptual and empirical articles and studies related to cultural wailing.The search was executed between January 2018 and March 2018 and resulted in a sample of 27 studies for this article, dated from 1985 to 2017.Aftercollecting data from 72 qualitative interviews,[2] stressed the important role of nurses while describing the bereavement practices of group wailing in the Australian aboriginal culture.Western health care professionals can view the mortuary rituals of traditional Aboriginal people as archaic and shocking. Nursing practice based in the notion of cultural safety requires not mere tolerance but rather a respect that fosters ownership of such practices by the community and ensures that the appropriate support and policies are in place to facilitate that expression of grief [7].

Other studies were nonspecific in their sample sizes;for example, [8] described interviewing 24 men, yet fails to provide a sample size of the women who were wailers in the community.“Participant observations and twenty in-depth interviews conducted with wailers as well as other members of the Yemeni-Israeli community in 2001-2002 demonstrate how the construction of wailing consists of several interwoven perspectives”[9,10] a nurse scholar,describes death practices of Tibetan Buddhists which include wailing practices. Most of the articles retrieved, such as that of [11], chronicle the wailing practices of groups or communities[12], a nurse, describes one instance of observing cultural wailing. Five electronic databases were the basis for the search and included Academic Search Premier, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and Google Scholar. The search was confined to peer-reviewed articles in the English language. Key search terms included cultural wailing, diverse cultures, indigenous cultures, and nursing.

Review of the Literature

Although very few studies of cultural wailing exist in the nursing literature, the phenomenon has been studied in severalother disciplines, including anthropology, art, communication studies, religious studies, and sociology. All the research on cultural wailing has been conducted in diverse populations[13]. For example, the phenomenon has been studied in the artistic work of Caroline Sardine, whose images portray cultural wailing in subjects who inhabit the Caribbean islands [14,15]wrote about keeners,portrayed as the wailing women in the Book of Jeremiah, and their role in Judah [16]chronicled a reconceived form of wailing in a description ofonline obituaries, bestowing upon this phenomenon the title “virtual wailing wall.” Private bereavement rituals for families have become a forum for anyone to engage in and post messages of grief and loss to the community. Thus, the need to grieve has entered the realm of social media with implications for the advancement of technology and redefinition of true presence. This was also seen in the horrific loss of life at an Ariana Grande concert involving teens in Manchester, UK, where a suicide bombing took place and wailing images of individuals expressing grief and disbelief were aired on national television. The news waveswere inundated by hundreds of instant tweets[17,18] explained how Zhang Xiaofeng, a Taiwanese writer and playwright, used Psalm 137 to describe the Six-Day War in China. The psalm is a biblical lament in the form of a prayer at the Wailing Wall in Jerusalem expressed in verse: “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept”[12].In another ritual practice, as recounted by[5], cultural mourning as wailing “still persists in the Yemeni community in Israel and is performed by a special woman wailer who composes memorial lyrics for the deceased and chants them in a sorrowful melody in the home of the bereaved family”. Studies have shown that wailing can go on for hours.

Two articleswere found in nursing research that examined cultural wailing [4] have been cited in the opening paragraphs of this manuscript with their description of a situation involving the coming together of an entire community to mourn the death of a beloved and respected member of their populace[5] described a situation in which wailing was occurring and the family disregarded the nurse’s attempts to quiet them; however, when the physician arrived, the mourners listened to him and took his suggestion to move with the deceased to the chapel area.

Non-Wailing Studies

Smith-Stoner[15] has described the bereavement rituals for best practices in nursing for end-of-life care for Tibetan Vajrayana Buddhists. In contrast to cultural wailing traditions, this Buddhist sect holds a negative view of the practice; if a person is crying, they will be asked to leave the bedside of the dying Buddhist. Their belief is that the sound of crying may interfere with the crossing of Phowa, which bridges the gap from life to death, thereby impeding transcendence to the “Pure Land”[19].

Similarly, a study by [20]suggested that Christian bereavement rituals are symbolic communications that “bridge the gap between humanness and the divine”. Utilizing exemplars with reflection on the ritual aspects of a funeral,Davisdescribes the funeral as a pulling together of the community in support for the survivors. She does not indicate any aspect of Christian funeral practices that includes lamenting or wailing.

Materials and Methods

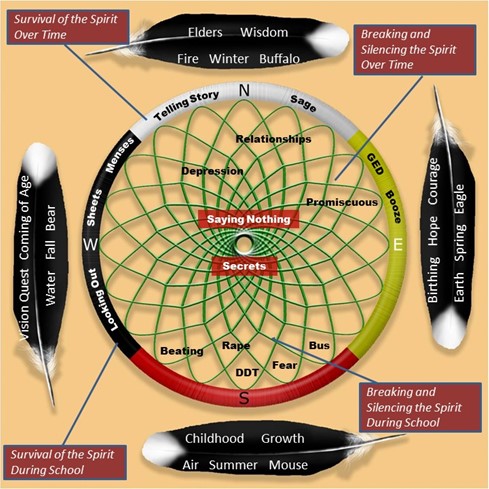

This is the third paper in a series related to the original research of the author[21]. The first paper utilized thedesigning and implementation ofthe Dream Catcher-Medicine Wheel (DCMW; see Figure 1) as a culturally appropriate data collection tool to facilitate the capturing of the storiesofnine female American Indian (Lakota and Chippewa)mission boarding school survivors. The Dream Catcher is a traditional Plains Indian cultural symbol envisioned as catching bad dreams in the webbing, which, through prayer, are filtered out through the center opening where they can no longer cause torment[22]. Research participants made notations of traumatic events in the webbing in the Dream Catcher,thus providing a visual depiction of how the experiences are woven into the complex lives of the participants (see Figure 1). The center openingthe therapeutic releaseof traumatic memorieswas provided by the very act of victims divulging their stories to a compassionatelistener. Notations were also made along the perimeter of the Medicine Wheel, which is another Plains Indian cultural symbol that represents the sacred cyclicaljourney of life. This was an integral part of my symbiotic allegory methodin that itfacilitated the establishment of the cultural bond insiders share, resulting in the unleashing of extremely candid accounts of trauma and abuse.

Dream Catcher-Medicine Wheel

The Dream Catcher-Medicine Wheel is a culturally appropriate method of data collection. It was designed by the author specifically as a way to invoke trust with the interviewees who are Lakota and Chippewa Plains Indian mission boarding school trauma survivors. It provides a nonthreatening way to recapture horrendous memories within the framework of a familiar healing and wholeness tradition. The research participant jotted notes on the image describing traumatic events and placing them in the webbing and along the hoop in the area that represents the part of their lives that were most impacted by the event (see Figure 1). This permitted the survivor to envision the events from a cultural perspective that helped them to make sense of the trauma and its role in shaping their lives.In the second paper, this author elaborated upon the concept of symbiotic allergy as an indigenous methodology[22]. The complexity of understanding indigenous methodologies are not always understood in Western universities because of cultural research paradigm demands [23].

Finally, this third article focuses on cultural wailing, to whichall nineof the femalessuccumbed while describing their experiences. The participants were recruited through snowball sampling and word-of-mouth by members of two communities where a high number of American Indian people live. No flyers or other means were utilized to recruit participants. All participants signed a consent form before the interviews were conducted. There were no exclusion criteria. Men were not referred to the author by the participants. Bias control was enhanced through mentorship during a practice storytelling session with Dr. Patricia Liehr, an expert in story theory[24]. Each of the dialogues was opened by a single question: “Can you tell me the first experience you remember about attending mission boarding school?”In every case, intense wailing accompanied the divulgence of the grief-ridden stories that ensued.

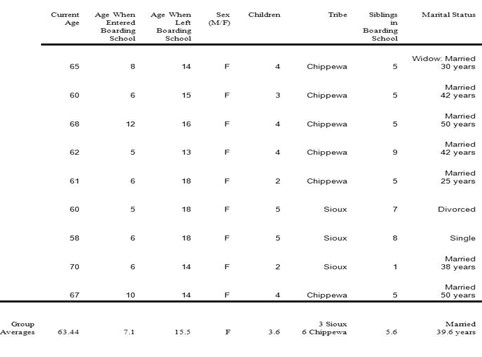

This study involves secondary analysis of the tapesand transcriptions of interviews of indigenous mission boarding school survivors derived from the author’s original research. The University Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Florida Atlantic University, Baca Raton, FL approved this study. The researcher completed the required IRB training for the study. After each of the nine women signed the consent form,demographic information was collected, including age when sent to the boarding school, age when they left the school, tribe, marital status, and the number of children they had seenTable 1.

Excerpts from the interviews of these three examples of cultural wailing related to remembered childhood trauma are provided in the following paragraphs. The first exemplardescribesthe woman’s intense weeping over the memory of fear related to humiliating sexual abuse inflicted by a nun in front of all of her classmates. In the second, a womandisclosesthe childhood memory of being rapedin the church by a priest. The final exemplar involves anotherwoman who was also raped by a priest as a child. The stories were accompanied by varying degrees of wailing and will be described to address these three questions:

Exemplar 1: Sexual Abuse in Front of Peers: In response to the question, “What was your first memory of boarding school?”the first participant replied, “Fear.” Moments later she began to wail in soft, low, and heavy tones laden with despair. She struggled to control the crying but she kept gasping the word fear. I asked if she needed me to shut off the tape recorder and she nodded to say, “Yes.” For more than an hour she cried, holding her arms tightly folded. When I offered to make tea for us, she again nodded to say,“Yes.”Through my patient acceptance and by allowing her time to just sit quietly, Ienabled her to transition back to a state of composure and resolve to complete thetellingof her story. Then the elderly woman picked up the image of the Dream Catcher-Medicine Wheel image and wrote the word “fear” on the webbing of the dreamcatcher, saying that this fear has loomed over her all her life. She went on to describe the sexual abuse inflicted by a nun upon her as a pubescent girl[24].

When I was leaving the dorm, a nun called out my name and asked what I had under my sweater. I replied, “Nothing.” The nun made me pull my sweater up. The nun then reached inside my bra feeling my breasts and around to my back. I stood frozen and screamed. “I know you put toilet paper in your bra to make them [breasts] look bigger,” the nun said. She put her hands in [my bra] and felt again and then screamed,“Remove your bra!” I did not and she slapped me across the face. [I endured] all this humiliation in front of the other girls in the dorm.

Exemplar 2: Rape in Church Balcony: Another woman described being raped by the priest, I was in the church helping another student dust the pews. And, when we finished, we were leaving the church, and Father [the priest] called to me as he was standing in the steps going to the balcony. He said to go upstairs.And when I did, he grabbed me from behind and turned me violently around. I felt like he was going to chokeme to death[25].

Her sobbing induced a rush of emotion and the tape recorder had to be turned off. Her uncontrollable crying was high-pitched while her body was trembling violently. I felt like I could feel her experience, and we both sat and cried. Finally, I asked her if she wanted to have me burn sage (another traditional Plains Indian ritual believed to invoke spiritual cleansing) and she nodded to say, “Yes.”We prayed, cried, and chanted on and off for several hours. When she was able to transition back to the interview, she said she had never told her story to anyone. At the conclusion of the session, she said,“I hope the world will hear us.”

Exemplar 3: Rape at Baptismal Fountain: A woman who had repeatedly been sexually abused as a child by a priest disclosed the threat the priest had repeated each time he violated her. Then he drugs [sic] me from the back over to where they baptize the children. And he just looked into my eyes, and he said, “Remember: anything that happens at [name of boarding school] stays at [name of boarding school]!”

As she recounted this story, she sobbed and was barely able to speak, with highs and lows in volume, pitch, tempo, and intensity.She cradled her head while tapping her brow and rocked back and forth, trying to sooth herself. She appeared as though she was experiencing severe throbbing pain [26].

Findings

Among other atrocities, the women described how, as boarding school students, their hair had been shorn, and their hair and bodies were thoroughly dusted with dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly referred to as DDT. This pesticide, developed after WWII to insect control pests, was banned in 1972 because of the harm caused to the environment and humans (Pesticide Action Network, n.d.). In addition,their clothing was burned, and personal belongings and comforting mementos were destroyed. Childhood playtime was replaced with rigid discipline and hard labor, correspondence with family was censored, and children were severely punished if they spoke their native language. In the case of the adults interviewed for this study, they were wailing over the resurrection of traumatic childhood memories involving sexual abuse at the hands ofreligious persons of authority who were their care takers. Wailing gave time and space to allow for expression of grief over sexual trauma that could not be immediately voiced, and, in fact, had never before been voiced [27].

As an indigenous researcher and nurse scholar, and in keeping with and knowing indigenous traditions of the Lakota and Chippewa participants, when aninterview session had to be paused due to wailing, I would embrace eachwoman (with permission) and allow time for her to wail. While listening to the recordings of the interviews, I was cognizant of the observation of another researcher: “Ritual wailing, like music or poetry, makes use of a pattern”. Indeed, the pattern of wailing could be described as polyphonic with rhythmic flows of highs and lows, emanating thesounds of deep sorrow. The sounds also verified description of wailing at the loss of separation.

In order to trigger dialogical engagement,I had asked each participant, “What was your first memory of the mission boarding school?” As a display of cultural respect,I always allowed plenty of time and space for the women to respond, and made it clear that there would be no time limit for the interview. This absence of time constraints assisted with thetransition out of wailing. Burning sage and offering tea was cohesive with respected traditional cultural practices, and provided comfort, which also assisted with the transition out of wailing.

Table 2(below) provides a summary of the quality and characteristics of wailing exhibited by the women in this study that has been derived from the exemplars:

Recommendation

There is a lack of methodological rigor on this topic and this leaves an opportunity for nurses to engage in robust research to add to the body of nursing knowledge on cultural wailing and trauma. Future research should measure patient/client health outcomes and organizational factors that would foster accommodations to these and other cultural differences, affecting the quality of healthcare delivery and outcomes for the patient [28].

As cultural diversity in the world increases, so does the need for nurses to grow professionally in acceptance of others. The role of wailing in a diverse culture may be a factor in healing for the patient. In practice, nurses may encounter this phenomenon. The findings support the need for nurses to increase their knowledge of cultural wailing to better inform practice. The more knowledge nurses have, the better equipped they will be to provide compassionate care and to seek mutual problem-solving solutions.

Limitations of the Study

The limitations of the study included the small sample size and the fact that all of the subjects were female.The isolated geographic regions where the participants lived served as a limitation due to the number of travel hours required to meet with individuals. The research was limited to individuals representing two different tribes. There was a possibility of bias in that the researcher is an American Indian tribal female who has mission boarding school experience[29].

Conclusion

In order to help meet the needs of those they serve, nurses need to be confident about asking questions related to grievingand bereavement practices in diverse cultures. These accounts of cultural wailing may represent an unfamiliar phenomenon that lies outside the experience ofmany nurses. Through recognition of cultural differences surrounding bereavement practices and trauma, we may become more culturally sensitive to others and their beliefs. For this study, utilization of a culturally-sensitive model (symbiotic allegory and the Dream Catcher-Medicine Wheel) was instrumental in data collection. This approach helped participants be candid in sharing sensitive information. Providing adequate time, space, and culturally-meaningful comforts assisted in the ability of participants to transition out of wailing and persist through the pain of telling their stories.

Figure 1:Synthesis of Dream Catcher-Medicine Wheel with themes.

Table 1:Mission Boarding School Survivor Demographics (N=9).

|

Incident |

Body Movement |

Sound |

Duration |

Transition |

|

#1 Groping |

Arms tightly folded |

Soft, low, heavy toneGasping |

> 1 hour |

Embrace Tea Time |

|

#2 Rape |

Violent trembling |

High-pitched at times |

Severalhours |

Embrace Sage Time |

|

#3 Rape |

Head moving up & down |

Polyphonic (high, low) |

½ hour |

EmbraceTime |

|

Head cradling |

Rhythmical |

|||

|

Brow tapping |

Barely able to speak |

|||

|

Rocking back and forth |

- |

|||

|

Note:Table 2 depicts characteristics of the three participants described in the exemplars. The other six women in the study also wailed as they told their stories. |

||||

Table 2:Wailing Characteristics of Mission Boarding School Sexual Abuse Survivors.

Citation: Charbonneau-Dahlen B (2020) Cultural Wailing: An Indigenous Experience. Aus J Nursing Res AJNR-100013