Emergency Medicine and Trauma Care Journal

(ISSN 2652-4422)

Case Report

Pericardial Effusion and Myocarditis Secondary to Covid-19 Case Report and Management

Alsheikhly AS1*,Eltawagny M2, Howaidi A1, Azmi MD1,Hlaoui S2 and Humadi MAS3

1,2Department of Emergency, Hamad General Hospital, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

3Department of General Surgery, Hamad Medical Corporation. Doha, Qatar

*Corresponding author: Ahmed S Alsheikhly, Department of Emergency, Hamad General Hospital, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar

Citation: AlsheikhlyAS, Eltawagny M, Howaidi A, Azmi MD, Sharafeldien M, et al. (2020) Pericardial Effusion and Myocarditis Secondary to Covid-19 Case Report and Management. Emerg Med Trauma. EMTCJ-100051

Received date: 29 August, 2020; Accepted date: 08 September, 2020; Published date: 15 September, 2020

Abstract

The disease caused by the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 known as COVID-19 Influenza, has produced so many morbidities and mortalities in staggering numbers. By the time you read this, these numbers will have been risen significantly. We know that COVID-19 is usually producing profound pulmonary manifestations and can easily cause respiratory failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome. The primary manifestation of this disease is pulmonary in nature: loss of smell, taste, fever with dry cough, shortness of breath and pneumonia. Now several reports are suggesting that the virus also attacks the heart leading to rapidly deteriorated cardiac function.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become one of the most serious pandemics of the recent times. It is crucial and necessary to identify laboratory markers which could provide predictions for the severity as well as the prognosis of the disease in order to guarantee proper clinical care for the patients.

In this case report we describe a 37-year-old male patient who presented with a large pericardial effusion and confirmed COVID-19. The pericardial fluid was drained. Two more young male patients were diagnosed in the same month and hospital presented with high grade fever 38 C, shortness of breath with no significant medical or surgical cases, chest x-rays showed huge pericardial effusion and tamponade, confirmed to be COVOD-19 patients as well. We believe this is one of the first such reported cases in the region. Findings suggested the fluid was exudative, with remarkably high lactate dehydrogenase and albumin levels. We present some important findings to improve knowledge of this virus. We hope our data provide additional insight into the diagnosis and therapeutic options for managing this infection.Learning Objectives:

Keywords: COVID-19; Pericardial effusion; Tamponade

Case Description

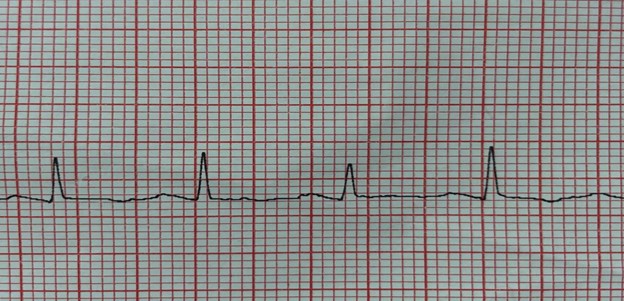

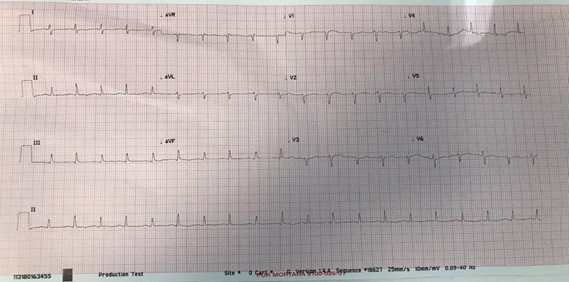

First case was a 37-year-old male patient who has no previous chronic diseases presented to the emergency department with history of 4 days fever, cough, shortness of breath and chest pain. His Physical examinations showing: Temperature was 37.3 C,pulse rate: 135 beats /minute, respiratory rate: 29/minute, blood pressure 135/88 mmHg and oxygen saturation 96% on 2 liters of oxygen.ECG showed tachycardia with electrical (pulsus)alternans with no ischemic changes (Figures1&2).

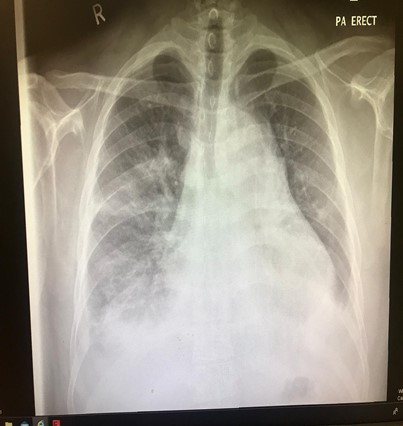

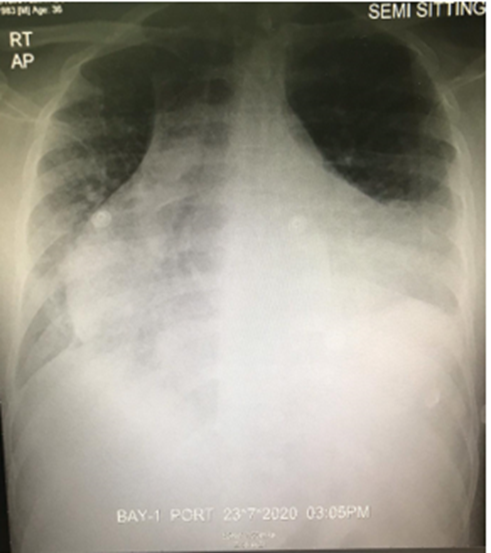

An echocardiogram demonstrated a large pericardial effusion more than 4 cm, with early signs of tamponade in the form of right atrial systolic collapse. A chest x-ray revealed cardiomegaly, and smooth cardiac boarders suggestive of pericardial effusion, in addition of pulmonary signs of peripheral consolidation mostly due to COVID 19 infection(Figures 3&4).

Basic laboratory blood tests reported high leukocytes, D-dimer, Ferritin and Lactate levels.A nasopharyngeal swab was positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction.

We found that the best view for tamponade assessment is subcostal view which can easily appreciatesthe right ventricular diastolic collapse and then inferior vena cava size and collapsibility can quickly be assessed in the same view, a timesaving approach.

The patient was reviewed and managed according to the COVID-19 protocol. Deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis and stress ulcer prophylaxis were initiated. Investigation of the pericardial effusion included an autoimmune screen, G6PD and thyroid profile.

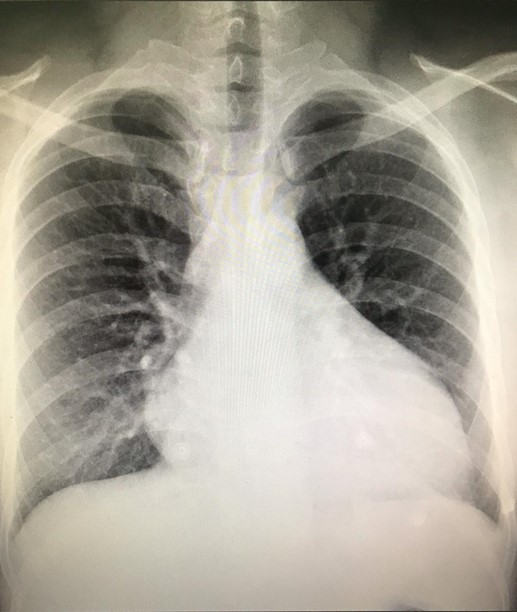

In view of the patient’s symptoms and the echo findings, pericardial aspiration was performed aseptically with appropriate PPE, and 550 ml of pericardial fluid was drained. Other two more young male patients (case 2&3) were diagnosed few weeks later with high grade fever 37.8 C and 38 C respectively with shortness of breath and no significant medical or surgical cases, chest x-rays showed huge pericardial effusion and tamponade(Figure 5&6), confirmed to be COVOD-19 patients as well.

We concluded that pericardial fluid from the 3 cases was most likely exudative, with remarkably high lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and albumin levels. Treatment of each patient was started by azithromycin 500 mg once daily for 5 days and hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily, as well as vitamin C 500 mg twice daily, vitamin D 500 units once daily. The patient had improved significantly by day 2,5&7 days respectively and were discharged well on day 10 to continue isolation at home.

For teaching and clinical purposes, we believe differential diagnosis included evolving coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia, acute-on-chronic heart failure exacerbation, acute coronary syndrome, acute pulmonary embolism, myocarditis, and pericardial disease.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a surge of information being presented to clinicians regarding this novel and deadly disease. As Coronavirus disease 19 was recently identified in China and is spreading across the globe [1, 2].

Symptoms are mostly respiratory but cardiac involvement has also been reported [3]. Cardiac involvement usually consists of myocarditis but the spectrum is widening as more cases are reported. Incidental pericardial effusion has been reported in 4.55% of all CT scans of the chest [4]. Our case seems to be unique, as the pericardial fluid was drained. The pericardial fluid showed elevated LDH and WBCs, while glucose level was unchanged.

To the best of our knowledge, we have described the first analysis of pericardial fluid in a COVID-19 patient with a large pericardial effusion. We hope our data provide additional insights into the diagnosis and therapeutic options for managing this infection. Cardiac involvement in COVID-19

COVID-19 can lead to cardiac involvement and injury via the following possible mechanisms:

(1) indirect injury due to increased cytokines and immune-inflammatory response.

(2) direct invasion of cardiomyocytes by SARS-CoV-2.

(3) respiratory damage from the virus causing hypoxia leading to oxidative stress and injury to cardiomyocytes[5-10].

These mechanisms are adapted from ACE2: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019[10].

Along with the presence of ACE2 in the respiratory tract, it is also found in the heart, and SARS-CoV-2 can use ACE2 to enter the cells [10,11]. The mechanism of heart injury in COVID-19 is still not entirely clear, i.e., it is unclear as to whether binding of SARS-CoV-2 alters the expression of ACE2 or causes abnormality in the regulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) [10]. However, multiple studies analyzing acute myocardial injury (AMI) in COVID-19-affected individuals have been published. AMI was detected by high levels of serum C-reactive protein (CRP), creatine kinase (CK), and troponins. Affected individuals often had a history of chronic diseases such as diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, and coronary artery disease (CAD). In general AMI could also be associated with a longer hospital stay [12-14]. Published studies have showed that critically ill patients could have a higher likelihood of myocardial injury, which was associated with poor outcomes and an increased risk of in-hospital mortality [15-19].

Conclusion

We reported a rare presentation of COVID-19 infection complicated by a large symptomatic exudative pericardial effusion and tamponade which had been managed by the classical COVID-19 protocols and pericardiocentesis.

\

\

Figure 1: (case 1): Electrical (Pulsus) alternans.

Figure 2: (case1): Electrical (Pulsus) alternans.

Figure 3: Chest X-Ray with signs of pericardial effusion, tamponade and pneumonitis.

Figure 4: Pericardial Effusion > 1 cm.

Figure 5: (case 2): Chest X-Ray with signs of pericardial effusion, tamponade and pneumonitis.

Figure 6: (case 3): Chest X-Ray with signs of pericardial effusion, tamponade and pneumonitis.

Citation: AlsheikhlyAS, Eltawagny M, Howaidi A, Azmi MD, Sharafeldien M, et al. (2020) Pericardial Effusion and Myocarditis Secondary to Covid-19 Case Report and Management. Emerg Med Trauma. EMTCJ-100051