Australian Journal of Nursing Research

Volume 2020; Issue 01

Review Article

Social, and Economic Aspect of Unpaid Care Effect on the Well-Being of Caregivers in Israel

ZoabiJ*

RN Certified Nurses School of Nursing Sherman in Afula, Israel

*Corresponding author: JehanZoabi, RN Certified Nurses School of Nursing Sherman in Afula, Israel, Tel: 0507506687; Email: shams1@walla.co.il

Citation: Zoabi J (2020) Social, and Economic Aspect of Unpaid Care Effect on the Well-Being of Caregivers in Israel. Aus J Nursing Res AJNR-100003

Received date: 16 March, 2020; Accepted date: 01 April, 2020; Published date: 10 April, 2020

Abstract

The need for caring -towards an adult, a child, or an ill person- may awaken at any given moment in our lives. Today, more than ever, a steadily increasing number of women are going out to work. Since care is a field that generally is provided by women, and they are usually the ones who assume the main burden in the care of family members and in the performance of the housework, they may feel a great load.

The topic of caring is important and becomes at some stage of life a need with important significance in the influence on the economic, culture and social well-being of society. However, there are differences between the various societies regarding care and the providing of care. Thus, looking at the topic of ‘Unpaid Care in Israel’ emphasizing the two important aspects in a country like Israel (Culture and Gender), enables us to see that Israel is a country that is complicated from social and multicultural perspectives. When looking at the issue from gender and cultural perspective, Israeli society appears to be a very complex case. It is dominated by Jews but there is also a large minority of Arab people, who represent different religions. There are Muslims, Christians, and Druse, and each of these groups has its own values and cultural customs.

This article addresses the effect of multiculturalism, economic and social context of unpaid care in Israel. The study was based on the 2006 Social Survey conducted in Israel in which one of the variables was unpaid caring. The final sample size was 7,500 people aged 20 and older. The sample involved 5 groups of three demographic variables: Arabs in East Jerusalem, outside East Jerusalem, immigrants who arrived in 1990 or later; immigrants who arrived by 1989; Israeli-born Jews.

The comparison and analysis of the results showed that the number,well-being and optimistic attitude of those engaged in paid caregiving are higher than in unpaid caregiving. Differences were found between the welfare of Arabs and Jews: Jews are more prevalent than Arabs. Jews are also higher in terms of the economic aspect.The research provides knowledge about the importance of caregiving and its significance for especially the growing older population in Israel on one hand, and on the other, it raises awareness and more questions about the importance of economic and social welfare of those who are involved in caregiving.

Keywords:Economic aspect; Israel culture; Social aspect; Social Well-Being (SWB); Quality of Life (QOF); Unpaid care

Introduction

When focusing about caring's importance according to the scientific literature, one can see that the demographic changes in the population has major importance among European countries. The aging of the population and the growing demand for caring in the elderly, and may increase even more in the future. It can be noted that the family is known to represent one of the most important sources of caring. Thus, the ongoing demographic aging process is a deliberate economic challenge that aging is imposing. One of the problems that arises from the aging of the population is long-term care. For example: It requires health insurance both in private and in public terms, and only a few countries have established long-term care insurance systems, as this requires a lot of economic resources for older people and their family members[1].

The Israel context of the problem: Studies shows that full-time jobs work load costs about $ 25 billion a year. Part-time work absenteeism is assessed as exceeding$ 28 billion.Theabsence from care of older family members refers to data regarding the United States[2]. In Israel the issue is emphasized and the Central Bureau of Statistics notes that the growth of population 65 and older began in 1948, in which they were only accounted for 4% of the population. The report also predicts that by 2040, the number will increase to 14.3% of the total population, and by 2065, itis expected to be 15.3%, with 4% of the Jewish elderly over the age of 75 and 35%of the Arab elderly (Live, 2017). Thus, a large elderly population requires rethinking from policymakers regarding the care given to this population and the necessary human and economic resources. This increase was noted by [3]that stated that the increase of the elderly population in Israel is one of the highest in the Western world and will increase further. The care of the elderly population is an important need for the developing countries.

Significance in the field of economy:According to Graham (2005) the happiness economy is an approach to the assessment of well-being that combines techniques used by economists, as well as psychologists, who rely on surveys that report the well-being of hundreds of thousands of people around the world and continents. It also relies on broader concepts of service than conventional economics, which emphasizes the role of income-less factors that influence welfare. It is well suited to inform questions in areas where the preferences exposed provides limited information like the fact that the effects of inequality and macroeconomic policy, such as inflation and unemployment. One such question is the gap between economists' assessments of the cumulative advantages of globalization and other pessimistic assessments typical of the public. It can be noted that new lines of research have been developed on happiness and economics-representing one new direction - that is based on more expansion of concepts of utility and welfare, including interdependence functions.

The aim of this article

Is to examine social, economic & cultural aspects of unpaid caregiving effect on the well-being of caregivers in Israel as result of the increasing need for caring among family members due to quality of life and an increase in the age of the population. It was based on an analysis of data of the social survey 2006 conducted in Israel and examined various aspects of unpaid caregiving.

Background

Well-being in the social science (sociology):The subject of well-being has beenstudied widely in various levels: personal, organizational or the personal work life. In each of these domains, well-being has a significant importance and meaning on the influence on man and society life. Recent studies in the social capital literature and in happiness economics suggests that Social Well-Being (SWB) does not only depend on the consumption of market goods and services but also on non-market, hereafter on non-economic relations [3].

Vast literature analyzes the effect of social capital on SWB and there is a debate about the relationship between income, as a means of consumption, and SWBwhich is found in happiness economics. One need to relate also to the concept "social cohesion", which is mainly used by sociologists and political scientists, policy makers in the developed countries and can be considered as a condition for political stability, as a source of well-being and of economic growth and as a justi?cation for public spending on social policies. Thus, there is a great need in future research of the concept[4].

A closer look at the concept of social cohesion and its definitions, shows that there are strong similarities, but also differences between these concepts. Therefore, a great importance is that in analyzing the relationship between social capital and SWB, the concept of social cohesion has to be includedin order to get a better understanding of the relationship between SWB and social variables without neglecting the economic aspects[4].It's impossible to ignore the social perspective of well-being and its great importance [5] suggests that the general prevalent opinion of people is that the goal of every democratic government is to promote a Quality of Life (QOL): The objective is to achieve a prosperous life and happy people. The meaning of life is crucial for individual’s well-being. According to the literature, it can be thought to represent social progress. A high level of well-being contributes to many positive outcomes such as better health and higher work output, both of which lead to economic growth in the country [5]keep up and states that people's well-being in society, has the potential to renew and reconnect the relationships between them and the policymakers, thus contributes to decrease the high levels of the citizen’s disconnection in the political process.

Well -being in theory of economy:Human well-being is not a very clear concept in its definition. The universal definition has a lot of interpretations. It's well known that human well-being cannot be measured directly and naturally in broad dimensions, although it is defined by terms of QOL, well-being, life satisfaction, human well-being developed over time[6]. According to the economic definition of well-being, higher levels of income are associated with higher levels of well-being. As income increases a greater number of needs are satisfied (due to an increase in consumption) and a higher standard of wellbeing is attained. The preoccupation of economists to increase per-capita income arises from the economic definition of well-being[7].

There are several economic theories that examines well-being and economic aspects such as:

The mainstream economic theory sets aside goals or aspirations: It focuses chiefly on pecuniary conditions and assumes that an increase in the material goods at one’s disposal increases well-being. The implicit assumption consumption goods are that habit formation and interdependent preferences play no part in determining the utility attributed to a given consumption set, and hence one’s feelings of well-being [8].

Relative Theory:Sustains that the impact of income on subjective well-being depends on standards that change over time according to the individual’s expectations and social comparisons. Thus, factors such as the relationship between the present and former economic situation and the individual’s wealth in relation to that of reference individualscould influence a person’s happiness regardless of his/her income level[8].

Setpoint theory: Each individual is thought to have a setpoint of happiness given by genetics and personality. Life events such as marriage, loss of a job, and serious injury may deflect a person above or below this setpoint, but in time hedonic adaptation will return an individual to the initial setpoint. One setpoint theory writer states flatly that objective life circumstances have a negligible role to play in a theory of happiness.

Absolute Theory: Assumes a relationship between basic needs satisfaction and subjective well-being. People with higher income levels can easily satisfy their basic needs (food, housing, health, etc.) and, therefore, attain a higher subjective well-being. Venhoveen’s approach suggests the existence of a threshold level where income’s impact on subjective well-being is not important [9].

Different Approaches to Well-being: Researchers have studied the topic of well-being from the Ancient Greece days until our time [10]mentions the importance of the approaches to well-being since they enable us to look at different aspects that have meaning and influence on the individual’s life daily and in general. Here are some of these different aspects:

• It enables a broad focus on what can make people’s life good and not only a narrow

look at what can disrupt people’s lives.

• An attempt to think about the means and ways in which people can improve them QOL and not only focus on the fact that people need help, are pitiful or lackingeverything.

• To consider the emotional and social needs of people and not only to focus on

economic circumstances.

If we understandwhat makes lives good, then we can see the things that will lead people to positive situations. The understanding of people’s emotional and social needs can provide a better solution to the many aspects that compose their lives. The emotional and social projects of people and services can become better when they are intended to provide a solution to the many aspects that comprise people’s lives[11].

Hedonic well-being:Notes that hedonism from the perspective of well-being is expressed in several different ways, which focus primarily on physical enjoyments and self-interests. Hedonism includes pleasures of the mind as well as of the body. From the prevalent perspective among psychologists, hedonism is well-being composed of subjective happiness and fears. The attempt of enjoyment versus broad discontent will be interpreted in general by the good or bad elements of life. Happiness is not restricted to physical hedonism but can derive from the achievement of goals or will be evaluated by outcomes in diverse fields.

A different perspective states that hedonic well-being is a mental situation of the person who needs to be happy and has experienced events of enjoyment. In mental health, well-being means to feel good with life, when hedonic well-being is generallymeasured by questions about the mood or satisfaction in two aspects, positive or negative[11].

Eudemonic Well-being:Maintain that many philosophers and clerics, both from the East and from the West, denigrate the idea and the approach that says that happiness is the main criterion of well-being. While happiness is defined as a perception of well-being that calls on people to live according to what occurs in their lives, eudemonia is the true self that offers many actions that merges with holistic values. Aristotle described well-being as the aspiration to wholeness, when this represents the fulfillment of the person’s true potential. Aristotle means that well-being is not simply the achievement of enjoyment alone [12]also note that Eudaimonia is well-being that describes a mental situation of self-fulfillment and fulfillment of the individual’s personal potential. Eudaimonia is measured generally through the individual’s autonomy, environmental control, positive relations, self-acceptance, goals in life and personal growth.

Caregiving in economic aspect:Theories and models of caring have been developed since the time of the nurse Florence Nightingale. Caring has been studied in many clinical settings philosophically, theoretically, ethically and ethnographically. The common denominator of the study of care and caring is that care and caring are essential and central and this is a dominant area that differentiates caring from most other professions [13] noted that in about 25% of North Americans and Europeans populations there is an expectation of significant increase of the 65 and older seniors. This aging can lead to a "crisis" forcing governments to look for methods and resolutions to restrict the issuance of state economic policy in terms of health.

A common view in economics, and one that has been criticized by feminist scholarsand activists, is that women’s work, which often includes unpaid labor and caregiving, is not considered productive, a view exemplified by national income accounting systems’ capturing only monetized labor for a nation’s gross domestic product [14].

While family caregiving may include caring for any family member, regardless of age, much of the current literature focuses on care of aging parents. Women have been and are continuing to be the primary providers of unpaid caregiving. Studies reveal several entrenched societal patterns that place women at a greater economic disadvantage for retirement security, and there is nothing in the data to suggest that positive change is on the horizon. Women’s employment patterns continue to disadvantage them in accomplishing retirement and later-life security. Continuance of these patterns suggests an urgent need for educational sessions to heighten awareness among caregivers, specifically women, about the financial and economic costs of caregiving and to promote tools for preparation for caregiving [15].

According to the Identity theory, the role of caring arises from an existing relationship, usually a family role such as a daughter, wife or husband. As the caregiver's needs increase in quantity and intensity over time, the first family relationships give way to a relationship The main change in identity requires a significant increase in the dependency level of the caring recipient [16]. Workplace and government policies and programs designed to support caregivers and/or mitigate these effects are discussed when caregiving is being studied. Caregivers of older adults can suffer significant financial consequences with respect to both direct out-of-pocket costs and long-term economic and retirement security. Spouses who are caregivers are especially at risk. More than half of today's caregivers are employed, yet current federal policy and most states' family leave is unpaid, making it difficult for many employed caregivers, particularly low-wage workers, to take time off for caregiving [17].The economic approach that addresses caring as work without emotions and as only the performance of activities, is not commensurate with the division of the characteristics of caring who studied the topic of care, noted five categories, most, if not all, of which address the emotional aspect:

It is possible to note that the word care is widely used, with a multiplicity of moral meanings that touch upon the concepts of duty and love mentioned this aspect as a part of the definition of care. The topic of care here is noted as completely emotional, when emotions of compassion, love, and need to provide help are what lead the person to give help.

The Importance of Caring in the Israeli Society

According to the data of the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, at the end of 2014 the population of Israel was about 8.3 million people. The elderly population was 900,000, constituting 11% of the population. In other words, in one of every four households in Israel there is somebody who is 65 years or older. The Arabs (Muslims, Christian Arabs, and Druse) represented 8% of the population. The Arab population is a relatively young population. The percentage of the elderly in the Arab population is 4%, in comparison to 13% in the Jewish and others (non-Arab Christians, and people without religious classification). The forecast claims that in the year 2035, the population of the elderly, according to the Central Bureau of Statistics, is expected to reach 1.66 million, a rise of 84% from the year 2014 in historical terms. The percentage of the elderly in the general population has doubled since 1950 and is expected to reach 15% by 2035. The percentage of Arabs in the elderly population is expected to rise from 8% to 14%. The rate of increase of the elderly population is expected to be 2.3% of the general population.???????

Nevertheless, Israel is still a young country, ranked first among the members of the OECD in the percentage of children under the age of 14. The percentage of the elderly in Israel is still one of the lowest in the OECD. The fertility rate in Israel is in decline. The Central Bureau of Statistics expects that the fertility rate of Israeli women will decline gradually but nevertheless will remain relatively high, in comparison to the countries of the Western world and adjacent. In the years 2006-2010 the fertility rate in Israel was an average of 2.95 births per woman. In the years 2031-2035 the estimate is that it will be at a level of 2.75.

According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, the life span of Jewish men is expected to increase from 79.7 in the period 2006-2010 to 84.8 in the period 2031-2035 while the life span of Jewish women is expected to climb from 83.3 to 89.5. The life span of Arab men will rise from 75.9 to 81.6, while the life span of Arab women will increase from 79.7 to 86.3, according to forecasts.

Israel as opposed to the other developed countries has a low population of elderly. For example, in Germany, Italy, and Japan, for example, the percentage of the elderly in the general population (an average of 22%) is double than of Israel, while in Europe it is 17%.Care of Elderly People is an important need for the developing countries and in the family status of the elderly population in Israel[18-20].

Living Arrangements: 46% of the elderly in the community (97% of the elderly in Israel) lives in a household framework of a couple without children, 23% live alone, 12% live in a household that includes a couple with children, 5% live in a household with a single parent with children, and 14% live in different types of arrangements. The elderly who do not live in the community (about 3% of the elderly population) live in nursing institutions (old age homes, hospitals for the chronically ill, or other frameworks).

Thus, it is possible to see the need for care. A research study conducted by the OECD which examined the topic of the most developed economies in the word, including Israel, defines the elderly as people aged 75 and above.(Linder-Ganz., 2011) The OECD estimated the readiness of the member countries to provide care for their elderly populations. The main problem is to provide comprehensive care for the elderly because their number is supposed to increase significantly in the coming years. The OECD cautioned that these requirements will have significant economic implications considering the high cost of care given. The Israeli Ministry of Health has announced that it will formulate a plan to provide a solution for the increase of the elderly population of the country.

The percentage of work in the Western countries addressing the care of the elderly is approximately 1-2%. However, this percentage is expected to double itself until the year 2050. The OECD says that in Israel the percentage of foreign workers who provide care of the elderly is now the second highest in the OECD, after Italy. Half of all care-providing workers in Israel are foreign workers. Additionally, 90% of care-providers are women and most are not young. The field suffers from a high rate of turnover, which influences the quality of the care methodology:

???????The survey population:The survey population comprises the permanent non-institutional population of Israel aged 20 and older, as well as residents of non-custodial institutions (such as student dormitories and independent living projects for the elderly). New immigrants in absorption centers and in general, were included if they have been present in Israel for at least six months. East Jerusalem was included in the Survey population and in the estimates of the table generator. Not included were residents of custodial institutions (e.g., old-age homes, hospitals for the chronically ill, prisons), Israelis abroad for more than a year without interruption at the time of the survey, diplomats as well as Bedouin and other persons living outside the boundaries of localities.

The survey frames:The Social Survey is the first survey conducted by the ICBS using the Population Register as a sampling frame. The quality of the sampling frame depends usually on the degree to which it covers the survey population to prevent under coverage leading to biased estimates, or over coverage leading to higher costs due to attempts to enumerate persons who are not part of the survey population. Thus, persons not belonging to the survey population were removed from the sampling frame. For example, Israelis permanently resident abroad are not part of the survey population (even if, from time to time, they return for brief visits), and efforts were made to identify them and remove them from the sampling frame. The Population Register contains demographic information which enables to improve the efficiency of sample selection based on characteristics such as sex and age. On the other hand, address inaccuracies in the Population Register requires the ICBS field staff to track sampled respondents to their actual address to enumerate them. This increases the likelihood of non-response by those not located.

Sampling method:The desired final sample size was 7,500 people aged 20 and older. The sample design involved groups of three demographic variables: Five population groups (Arabs in East Jerusalem, outside East Jerusalem, immigrants who arrived in 1990 or later; immigrants who arrived by 1989; Israeli-born Jews); Seven age groups (20-24, 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64, 65-74, 75+); men and women- a total of 70 design groups. The expected size of each design group was to be proportional to its size in the population, under the constraint of a final total sample size of 7,500 completed interviews.

The final sampling probability for each person varies by design group and reflects a-priori assumptions regarding the proportion of non-response for each group. The average sampling probability was 1:523, the maximum sampling probability was 1:406, and the minimal sampling probability was 1:586. People listed in localities from which it was expected to obtain sample sizes of at least 15 people (i.e., whose population of people aged 20 or older was at least 7,800), were sampled in a single-stage stratified sample, with each design group comprising a stratum. A systematic random sample of people with a uniform probability was drawn from each stratum after it was arranged according to the geographic characteristics of the localities it contained. Altogether, about 84% of the sample was drawn in single-stage sampling. The second stage sampling probability was set such that the overall sampling probability (the product of the probabilities in each stage) would be constant. This method provided the minimum required number of 15 people per locality. The initial sample included 9,389 people to obtain 7,500 responds.

Results: Data analyses of main research questions and statistical results

Q1: How does caregiving influence the well-being of caregivers?

To test if being paid for caregiving affects the well-being of caregivers, independent t-test was conducted, testing differences in well-being comparing paid and unpaid caregiving. It was found that caregivers who are paid for their caregiving, report on higher well-being today (M=2.79, SD=0.66) in comparison to caregivers who are not paid (M=2.52, SD=0.60) t(2050) =7.953, p<.001. In addition, it was found that caregivers who are paid for their caregiving, report on higher optimism (M=2.37, SD=0.64) than caregivers who are not paid (M=2.23, SD=0.64) t(1922) =4.135, p<.001.

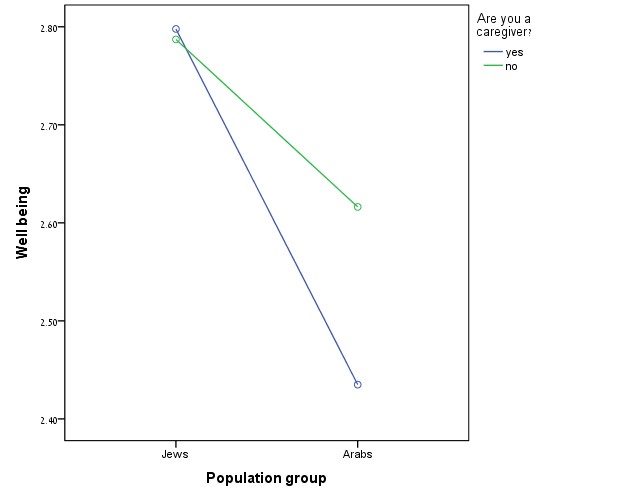

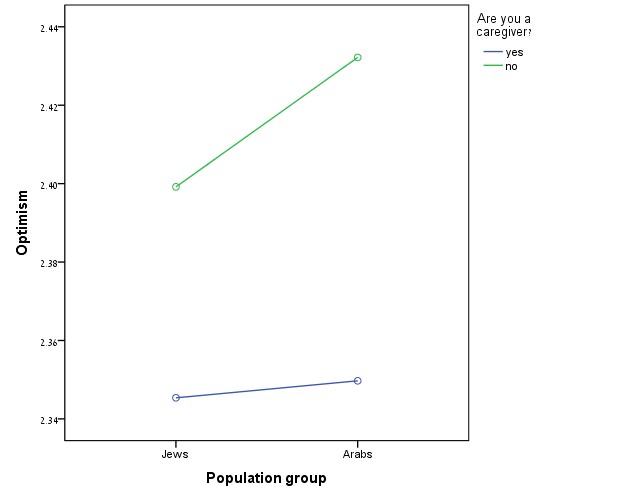

Q2: How does Jewish and Arabic culture affects the caregiving effect on well-being?

To test if and how culture and being a caregiver affect wellbeing, two-way MANOVA was conducted see Table 1.

The analysis yielded a significant interaction for well-being (F(1,6847)=15.41, p<.001). Interpretation of this interaction showed that while among Jews no difference was found between caregivers and non-caregivers (t(6236)=0.663, p=.507), among Arabs, lower well-being was reported among people who are caregivers(t(1045)=3.546, p<.001).

No interaction was found between culture and being a caregiver on optimism (F(1,6847)=0.385, p=.535), and no difference between Jews and Arabs in optimism by caregiving.

Q3: What is the effect of the amount of time spent on care on well-being of caregivers?

Pearson correlations werecomputed between variables.

As seen in Table 2, optimism was negatively correlated with years of care (r=-.059, p<.01) and frequency of care (r=-.144, p<.01). In addition, optimism was positively correlated with time spent on caregiving (r=.115, p<.01). That is, lower optimism is correlated with many years of care and higher frequency of care, but with more time spent on caregiving.

Well-being was found to be negatively correlated with Frequency of care (r=-.131, p<.01), but positively with time spent on caregiving (r=.124, p<.01). That is, lower levels of well-being are associated with less frequency of care but with more time spent on caregiving.

Q4: What is the effect of caregiving for elderly people vs caring for children on the well-being of caregivers

Two-way MANOVA was conducted see Table 3.

Analysis showed that caregiving for children results in higher well-being (F(1,2386)=166.49, p<.001) and also higher optimism (F(1,2386)=11.98, p<.001) in comparison to caregiving of elderly people.

Finally, to examine how all main variables tested above influence well-being and optimism of caregivers, multivariate linear regressions were conducted for both dependent variables.

As seen in Table 4, after controlling all other variables, Arabs were found to have lower well-being than Jews (β=-.121, p<.01). In addition, people who are also taking care for their children, report on lower well-being in comparison to those who don't (β=-.233, p<.01).

As seen in Table 5, after controlling all other variables, the only variable that was found to be nearly significant in predicting optimism is taking care for children. It was found that people who take care for their children in addition to their parent’s report on lower optimism in compare to people who don't (β=-.089, p=.06).

Conclusion

This paper refers to the welfare of caregivers in Israel, whose reference was the effect of caring on the well-being of caregivers (Easterlin 2006), noting that a person's well-being is influenced by economic material issues. Paid Caring has positive effects on caregiver's optimism vs unpaid Care. As a result of population growth, there is a very significant need for care and this is part of the burden on the family, which affects the economic aspect of the individual who gives care, who loses working days and also hassocial impacts due to disconnections from friends.

From the point of view of Israeli society, the Jewish society and Arab society are divided roughly into two parts. It can be noted that according to the statistical projection data, the welfare of Jewish caregivers is higher than that of Arab caregivers. In a follow-up study it is important to examine whether there are gender differences in caring in Israel

Figure 1: Differences between caregivers who get paid and don't get paid.

Figure 2: Differences between Jews and Arabs in well-being according to being a caregiver.

Figure 3: Differences between Jews and Arabs in optimism according to being a caregiver.

|

|

Group |

Caregiver |

M |

SD |

N |

|

Well-being today |

Jews |

yes |

2.80 |

0.67 |

1743 |

|

no |

2.79 |

0.67 |

4091 |

||

|

Arabs |

yes |

2.43 |

0.68 |

346 |

|

|

no |

2.62 |

0.75 |

671 |

||

|

Total |

2.55 |

0.73 |

1017 |

||

|

Optimism |

Jews |

yes |

2.35 |

0.64 |

1743 |

|

no |

2.40 |

0.63 |

4091 |

||

|

Total |

2.38 |

0.63 |

5834 |

||

|

Arabs |

yes |

2.35 |

0.73 |

346 |

|

|

no |

2.43 |

0.69 |

671 |

||

|

Total |

2.40 |

0.70 |

1017 |

Table 1: Differences in well-being and optimism by population group and caregiving.

|

- |

Years of care (in patient oldest) |

Frequency of care |

Time spent caregiving |

|

Well being |

-.041 |

-.131** |

.124** |

|

Optimism |

-.059** |

-.144** |

.115** |

Table 2: Correlations between well-being, optimism, and time spent caregiving.

|

|

Group |

Caregiver |

M |

SD |

N |

|

Wellbeing today |

Caring for children |

Caring for elderly |

2.93 |

0.56 |

441 |

|

Not caring for elderly |

2.89 |

0.61 |

710 |

||

|

Not caring for children |

Caring for elderly |

2.91 |

0.59 |

1151 |

|

|

Not caring for elderly |

2.55 |

0.66 |

343 |

||

|

Total |

2.54 |

0.71 |

896 |

||

|

Optimism |

Caring for children |

Caring for elderly |

2.54 |

0.70 |

1239 |

|

Not caring for elderly |

2.15 |

0.61 |

441 |

||

|

Total |

2.14 |

0.61 |

710 |

||

|

Not caring for children |

Caring for elderly |

2.14 |

0.61 |

1151 |

|

|

Not caring for elderly |

2.07 |

0.67 |

343 |

||

|

Total |

2.03 |

0.61 |

896 |

||

|

Note:Multi-variate analysis |

|||||

Table 3: Differences in well-being and optimism by caregiving to children and elderly people.

|

- |

B |

S.E. B |

Beta |

t |

p |

|

Payed for caregiving |

.043 |

.060 |

.031 |

.704 |

.482 |

|

Population group (Arabs) |

-.289 |

.104 |

-.121 |

-2.770 |

.006 |

|

Frequency of care |

-.013 |

.027 |

-.023 |

-.475 |

.635 |

|

Time spent caregiving |

.018 |

.024 |

.036 |

.742 |

.459 |

|

Caregiving for children |

-.293 |

.056 |

-.233 |

-5.230 |

.000 |

Table 4: Predicting wellbeing.

|

- |

B |

S.E. B |

Beta |

t |

p |

|

Payed for caregiving |

-.061 |

.066 |

-.045 |

-.934 |

.351 |

|

Population group (Arabs) |

.112 |

.109 |

.049 |

1.024 |

.306 |

|

Frequency of care |

-.026 |

.029 |

-.047 |

-.878 |

.380 |

|

Time spent caregiving |

.020 |

.026 |

.040 |

.767 |

.444 |

|

Caregiving for children |

-.113 |

.062 |

-.089 |

-1.830 |

.068 |

Table 5: Predicting optimism.

Citation: Zoabi J (2020) Social, and Economic Aspect of Unpaid Care Effect on the Well-Being of Caregivers in Israel. Aus J Nursing Res AJNR-100003