Emergency Medicine and Trauma Care Journal

Volume 02; Issue 04

ISSN 2652-4422

Research Article

Prospect of Tele-Pharmacists in Pandemic Situations: Bangladesh Perspective

Mohiuddin AK*

Department of Pharmacy, World University of Bangladesh, Green Road, Dhaka, Bangladesh

*Corresponding author: Abdul Kader Mohiuddin, Department of Pharmacy, World University of Bangladesh, Green Road, Dhaka, Bangladesh, Tel: +8801716477485; Email: trymohi@gmail.com

Citation: Mohiuddin AK (2020) Prospect of Tele-Pharmacists in Pandemic Situations: Bangladesh Perspective. Emerg Med Trauma. EMTCJ-100044

Received date: 22 April, 2020; Accepted date: 27 April, 2020; Published date: 08 May, 2020

Abstract

Telemedicine and telehealth technologies are especially effective during epidemic outbreaks, when health authorities recommend implementing social distance systems. Currently, coronavirus COVID-19 has affected 210 countries around the world, killed nearly 170,000 and infected more than 2.4 million, according to worldometer, April 20, 2020. Home-care is especially important in these situations because hospitals are not seemingly safe during pandemic outbreaks. Also, the chance to get out of the home during the lockdown period is limited. Telephone-based measures improve efficiency by linking appropriate information and feedback. Tele-pharmacy allows to electronically share measurements of several parameters (e.g. blood pressure or BP, electrocardiograms or ECGs, blood lipids and glucose, body weight, etc.) and information on medications and life style behaviors among care givers and patients. It can also help provide education at distance on various health issues and topics. In addition to increasing access to healthcare, telemedicine is a fruitful and proactive way to provide a variety of benefits to patients seeking healthcare; diagnose and monitor critical and chronic health conditions; improve healthcare quality and reduce costs.

Abbreviation

IEDCR : Institute of Epidemiology Disease Control and Research

Introduction

Bangladesh's health care services are becoming unusually concentrated in a small fraction of costly critical health-demanding patients. A large part of these complex-patients suffers from multiple chronic diseases and are spending a lot of money. Tele-pharmacy includes patient counselling, medication review and prescription review by a qualified pharmacist for the patients who are located at a far distance from the pharmacy. The most common way to use telemedicine is a responsive model, primarily physician-led with virtual visits stimulated by alerts using interactive services, which facilitates real-time interaction between the patient and provider [1]. It delivers resilience to services and enables pharmacists to work remotely, reducing the need for long journeys and increasing job satisfaction [2]. The rise of pharmacists in epidemic situations has become increasingly popular in developed countries such as the United States, Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom. According to information from recent published articles in several ongoing journals, books, newsletters, magazines, etc., the duties, authority and responsibilities of pharmacists are completely different from doctors and nurses, although there are some similarities. Along with doctors, pharmacists can serve as frontline healthcare workers during epidemics. The profession is developed and highly praised in both developed and underdeveloped countries (Figure 1). Millions of professional pharmacist’s worldwide work in various organizations, and according to data from the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP), nearly 75% of them work in patient care [3]. Even in the United States, the continued lacking of primary health providers and medical specialists has made it possible for pharmacists to care for ambulatory patients with chronic diseases in a variety of treatment services [4].

Materials and Methods

Research conducted a comprehensive month-long literature search, which included technical newsletters, newspaper newspapers and many other sources. The present study was begun in early 2019. PubMed, ALTAVISTA, Embase, Scopus, the Science Web and the Cochrane Central Register have been carefully searched. The keywords were used to search out extensively followed journals from various publishers such as Elsevier, Springer, Willey Online Library, and Wolters Kluwer. Medical and technical experts, representatives of the pharmaceutical companies, hospital nurses and journalists have made valuable suggestions. Projections were based on review of tele-pharmacists in both general and pandemic health situations, eligibility of pharmacists in telemedicine in general, present under-utilization scenario of Bangladeshi pharmacists in health services, let alone in telemedicine sector. Major infrastructure revolution in both pharmacy education and country’s technological advancement are necessary to build an effective telemedicine system in this country.

Present Socio-Economic and Healthcare Situation

Bangladesh is the seventh most populous country in the world and population of the country is expected to be nearly double by 2050 [6], where communicable diseases are a major cause of death and disability [7]. A recent Dengue outbreak in 2019, more than 100,000 people was affected in more than 50 districts in Bangladesh in the first 6 months of 2019 [8,9]. According to World Bank's Country Environmental Analysis (CEA) 2018 report, air pollution lead to deaths of 46,000 people in yearly in Bangladesh [10]. Although a riverine country, 65% of the population in Bangladesh do not have access to clean water [11]. Both surface water and groundwater sources are contaminated with different contaminants like toxic trace metals, coliforms as well as other organic and inorganic pollutants [5]. Studies in capital Dhaka and Khulna also found that about 80% of fecal sludge from on-site pit latrines is not safely managed [12]. Nearly half of all slum dwellers of the country live in Dhaka division [13] and 35% of Dhaka's population are thought to live in slums [14]. A recent research demonstrates widespread poor hygiene and food-handling practices in restaurants and among food vendors [15]. Less than 10% hospitals of this country follow the Medical Waste Management Policies [16]. In 2017, 26 incidents of disease outbreak were investigated by National Rapid Response Team (NRRT) of IEDCR [17]. Economic development and academic flourishment do not represent development in health sector. Out of the pocket treatment cost raised nearly 70% in the last decade [18]. Although, officially 80% of population has access to affordable essential drugs, there is plenty of evidence of a scarcity of essential drugs in government healthcare facilities [19]. Surprisingly, the country’s pharmaceutical sector is flourishing, exports grew by more than 7% in last 8 months although total export earnings of the country drop to nearly 5% [20]. It has been found in Bangladesh that more than 80% of the population seeks care from untrained or poorly trained village doctors and drug shop retailers [21]. According to WHO, the current doctor-patient ratio in Bangladesh is only 5.26 to 10,000, that places the country at second position from the bottom, among the South Asian countries [22]. According to World Bank data, Bangladesh has 8 hospital beds for every 10,000 people; by way of comparison, the US has 29 while China has 42 [23]. Tobacco is responsible for 1 in 5 deaths in Bangladesh, according to the WHO, kills more than 161,000 people on average every year. Around 85% population of age group 25-65 never checks for diabetes [24,25].

Pharmacy Education in Bangladesh

Pharmacy Education in many developing countries, including Bangladesh, is still limited to didactic learning that produce theoretically ‘skilled’ professionals with degrees. Pharmacy curriculum in Bangladesh do not satisfy the minimal requirement for appropriate education in clinical, hospital and community pharmacy, since they are still linked to an old model of pharmacy activity e.g. based on chemistry and basic sciences. That is present curriculum produces Pharmacist only to work in the pharmaceutical industry and jobs in this field of work is going to be saturated. No university so far have modified their curriculum including topics as epidemiology, pharmaco-economics, clinical medicines, community skills. Manpower development for community pharmacies in Bangladesh is not systematically regulated and constitute an important public health issue. Three levels of pharmacy education are currently offered in Bangladesh leading to either a university degree, a diploma or a certificate. Graduates with degrees work in industry while those with diplomas work in hospitals [26]. Pharmacy is taught in about 100 public and private universities in Bangladesh and about 8000 pharmacy students graduate every year [27]. Due to a lack of government policy, hospital, community, and clinical pharmacy in Bangladesh were not well developed [28]. In real Bangladesh pharmacy practice areas for graduate pharmacists in industry i.e. industrial pharmacy practices, in marketing or regulatory sections are limited. The educational system of pharmacy is one of the major reasons for bounded pharmacy practices because the courses included in bachelor degree principally emphasize on industrial practices [29]. Over 90% of B. Pharm curriculum emphasizes on product-oriented knowledge whereas only around 5% of the total course credits are allocated toward clinical pharmacy. This curricular framework indicates a minimum emphasis on patient care education [30]. However, the graduates who pass out do not get employment easily due to their poor training, lack of in-depth knowledge of fundamental concepts and practical skills [17]. Consequently, skilled graduates leave for overseas where they find more prosperous jobs. Researchers argued that Pharmacy Education can be able to contribute for both public and private benefits if a realistic pattern is ensured on its operation [31]. This system could be more beneficial to the public if the good hospital and community practices are introduced properly and also by involving the pharma professionals e.g. pharmacists and other skilled health care providers.

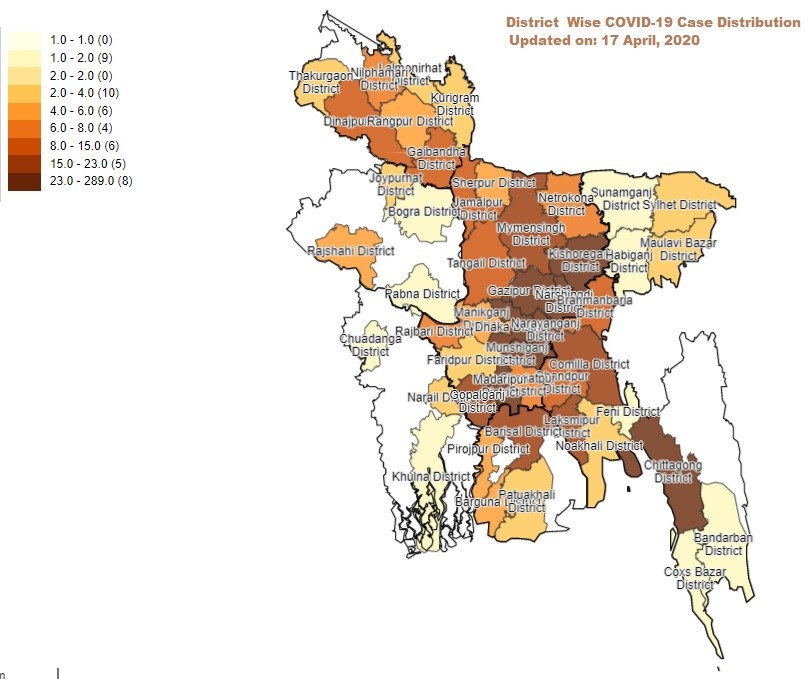

Present State of Pandemic Situation Handling by Bangladeshi Hospitals

Nearly half of the 2948 coronavirus cases detected in Bangladesh have been reported in the capital Dhaka [32]. The virus hit a total of 11 out of the 64 districts in the country until 05.04.2020 after the first known cases were reported around a month ago, according to the government’s disease control agency IEDCR [33]. Amidst this global crisis, Bangladesh has been identified as one of the 25 most vulnerable countries to be affected by the fast-spreading virus. From 1st April to 14th, Covid-19 cases became 20-fold and by 20.04. 2020, it was confirmed in 53 districts [34,35]. Many patients with fever, cold and breathing problems – which are also COVID-19 symptoms have gone untreated as the hospitals in Dhaka are sending them to the IEDCR for coronavirus test [36]. Many doctors are not providing services fearing the contagion and lab technicians are shunning workplaces halting medical tests, according to the patients. In some cases, serious patients who are not affected by COVID-19, moved from one hospital to the other but could not receive treatment and finally died, the media reported. In another case, the doctor fled leaving the patient behind [37-40]. Doctors and other healthcare workers say they do not have adequate personal protective equipment and the health system cannot cope with the outbreak [41]. Police have locked down a total 52 areas of Dhaka after Covid-19 positive patients were found in the localities [42]. Experts say elderly people infected with coronavirus need ICU support the most. The number of older persons in the country is over 0.8 million [43]. The country's entire public health system has less than 450 ICU beds, only 110 of which are outside the capital Dhaka [23]. The economic shutdown sparked by COVID-19 threatens millions of livelihoods in the country imminently. Law enforcers have been struggling to enforce shutdown and keeping people confined to their homes but people often ignored their request and instructions [44].

Under Utilization of Hospital Pharmacy

The pharmacy profession is still lagging behind in developing countries as compared with developed countries in a way that the pharmacy professionals have never been considered as a part of health care team neither by the community nor by the health care providers. Although hospital pharmacists are recognized for its importance as health care provider in many developed countries, in most developing countries it is still underutilized or underestimated [45-48]. Hospital pharmacy practice has just begun in some modern private hospitals in Bangladesh, which are inaccessible to most people because of the high cost of these hospitals to patients [49]. People are totally unknown to the responsibilities of hospital pharmacist, even they don’t seek for recruit for hospital pharmacist in any hospital except a few aristocrat hospitals [50]. A Dhaka survey found nearly 50% of the respondents with acute respiratory disease (ARI) symptoms identified local pharmacies as their first point of care. Licenses are provided by the Directorate-General of Drug Administration to drug sellers when they have completed a grade C pharmacy degree (i.e. 3 month course) for the legal dispensation of drugs [51] but a grade A pharmacy degree holder, having a B. Pharm or Pharm. D degree should be more equipped to handle these situations, if trained properly. Pharmacist's knowledge and helpfulness were identified as two key determinants which could not only satisfy and promote willingness to pay for the service [52]. They can individualize the medications and their dosing according to the needs of the patient, which can minimize the cost of care for the medication. In Bangladesh, however, graduate pharmacists do not engage directly in-patient care. Here, pharmacies in hospitals are primarily run by non-clinically educated, diploma pharmacists [28]. If the hospital pharmacy is established, patient care, proper dispensing of medications, and other patient-oriented issues can be handled properly. By maintaining a hospital pharmacy quality control program, the health sector can be enriched.

Prospect of Pharmacists in Patient Management Service and Telehealth Care

Pharmacists are the third largest healthcare professional group in the world after physicians and nurses [53]. At present, Hospital Pharmacy has created enormous job opportunities, where graduate pharmacists play a vital role in patient rearing, rehabilitation and wellness. A professional pharmacist or a pharmacy apprentice at a clinic, hospital and community care can determine what to do in a given disease situation, if guided properly by another medical personnel [54-56]. The country has a huge opportunity to recruit these pharmacists at Telehealth Care. In each call, a pharmacist can provide both appropriate and quality information from the most recent medical systems. Studies show that the lack of proper medication management leads to higher healthcare costs, longer hospital stays, morbidity and mortality. Further, it was reported that one in every five hospitalizations was related to post-discharge complications and about seventy percent were related to proper use of the drug. In 2017, the World Health Organization committed to minimizing serious, avoidable drug-related harm over the next 5 years. Pharmacists' interventions to prevent drug-related problems at three community hospitals in California saved approximately 0.8 million USD in a year [57]. The estimated annual cost of medication error-based illnesses and deaths worldwide was USD 500 billion due to non-compliance with the clinical intervention and quantities in 2016. Also, the authors estimate that more than 275,000 people die every year for the same reasons [58]. A pharmacist can use simple and non-medical terminology to set the goal for patients to understand the information as well as to fulfill the prescription by proper request. With chronic conditions such as cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, there is ample evidence of the effectiveness of the tele-pharmacist for remote monitoring, communication and consultation [59]. In addition, psychotherapy can also be operated through telehealth as part of behavioral health [60]. The pharmacy-related needs of pandemic patients have similarities with the traditional patient population, but with different emphasis [61]. For example, when providing consulting services to patients, instead of focusing on medications as usual, their queries relate primarily to the knowledge of medical prevention and basic details on COVID-19, such as mask selection and standard COVID-19 signs and symptoms, symptomatic treatment options, breathing difficulties or cough management in comorbid situations, reinforcing behaviors that limit the spread of the pandemic, including social distancing and remaining in the home whenever possible through phone calls/video conferencing [62,63]. Earlier, Student pharmacists served as an effective education resource for patients regarding the H1N1 pandemic [64]. Sorwar et al, 2016 revealed that the existing telemedicine service reduced cost and travel time on average by 56% and 94% respectively compared to its counterpart conventional approach with high consumer satisfaction [65].

History of Telehealth Service in Bangladesh

The year 1998 is a milestone for eHealth in Bangladesh since Swinfen Charitable, a not-for-profit institution, launched the first eHealth project. It involved a collaboration between the Bangladesh Center for Paralyzed Rehabilitation (CRP) and the Haslar Royal Navy Hospital, in the UK. The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) launched its first eHealth initiative in the same year [66,67]. Just a year later the private company Telemedicine Reference Center Limited (TRCL) started using mobile phones to deliver healthcare. A professional coalition, the Bangladesh Telemedicine Association (BTA) was created in 2001. That provided a platform for the country's ongoing and sporadic eHealth initiatives. A similar platform was formed in 2003, called the Sustainable Development Network Program (SDNP), with the aim of establishing better collaboration and understanding between providers [68]. Later in 2006, TRCL paired with GrameenPhone (GP) and established a subscriber mobile phone call center called Health Line:789 [69,70]. A number of NGOs, including BRAC, Sajida Foundation and DNet subsequently developed an interest in eHealth and mHealth [71]. Moreover, in December 2017, Bangladesh launched a toll-free national emergency aid line 999 for immediate needs in the event of any accident, crime, fire or ambulance [72]. Besides, there are 17 hotline numbers that were launched by the IEDCR for the said Covid-19 outbreak [73].

Challenges of Tele-Pharmacy Implementation

First, it has limited evidence of its efficacy beyond that of a traditional pharmacist’s intervention. This favor both doctors’ and patients’ skepticism towards these services and limits their diffusion in the community [74]. Second, the tele-pharmacy is a service based on the technology. Thus, the driver is technology but also the limiting factor for its implementation. Establishing a tele-pharmacy service involves not only meeting technological requirements but also a considerable amount of time, effort and money [75]. Third, effective tele-pharmacy services should be based on standardized models of healthcare provision and need appropriate regulations that may differ from one country to another. For example, in some countries such services are not permitted or even prohibited, while in others such as the USA, Italy and other European countries appropriate legislation is available [76-79]. Unfortunately, in many countries, despite the widespread potential of tele-pharmacy, the laws and policies that govern pharmacy operations do not adequately address the growing industry. Fourth, reluctance or inability to use modern technologies may limit the implementation of tele-pharmacy services both from the pharmacist’s and patient’s perspective, particularly in case of elderly people [80-85]. Fifth, since tele-pharmacy involves collecting, transmitting and replacing personal and health information on the Internet, security and privacy of information is a major issue. Data sharing of information collected with other healthcare professionals through tele-pharmacy services increases the risk of security breaches. The security and integrity of patient data is therefore of paramount importance when determining the setup of a tele-pharmacy system of information technology [86-91]. Sixth, the integration of tele-pharmacy services in the national healthcare systems and the connection of tele-pharmacy services (including a combination of electronic data entry, prescription order verification, online benefit adjudication, medication dispensing) among different areas of a country requires harmonizing the healthcare systems and related governing laws and setting up proper rules and regulations [92-94]. Seventh, tele-pharmacy services are not yet reimbursed: individuals have to pay for these services and the expenditures are not covered by private or public health insurances [95-99]. This limits the use of these services by patients eventually needing them.

Overcoming Challenges

In Bangladesh a number of telemedicine systems were introduced. Telemedicine laws and reimbursement policies since telemedicine practice is increasing on a daily basis in Bangladesh, so structured laws and regulations on doctors, patient issues, licensing of physicians and telemedicine providers are very much needed. Clear rules should be in place on questions of reimbursement. Bangladesh Television (BTV) and other satellite channels can play an important part in popularizing telemedicine. They should broadcast successful cases considering telemedicine's efficacy and cost-efficiency. Telemedicine systems and services compatibility of hardware and software require users to have compatible hardware at both ends of the communications link, which reduces interoperability and the benefits of access to different sources of telemedicine expertise. If the equipment is difficult to access or are less likely to involve practitioners. Equipment for wireless telemedicine is preferable to wire devices. Telemedicine privacy and confidentiality involves the electronic transmission of patient medical records and information from one location to another via the Internet, or other computerized media. Medical information is often delicate, confidential and private. Telemedicine, thus presents significant challenges for safeguarding the privacy and confidentiality of information about patient health. Specific privacy regulations should govern the practice of telemedicine so that patients can feel safe in knowing that confidentiality of their personal information will have to suffer certain penalties.

Conclusion

Overburdened by patient loads and the explosion of new drugs, physicians have increasingly turned to pharmacists for information about drugs, particularly within institutional settings. They acquire medical and medicinal history, check medication errors including prescription, dispensing and administration errors, identify drug interactions, monitor ADR, suggest dosage regimen individualization, provide patient counseling, etc. Among chronic disease patients, particularly those under quarantine, there is a greater challenge in the supply of drugs and compliance with medications, although the safety and effectiveness of care is still critical for these patients. Stronger data on the effectiveness of this area of pharmacy care, together with a critical assessment of its limitations, can raise awareness among the actors involved about its potential and could contribute to a wider dissemination of tele-pharmacy services in public interest. At the end, it can be said that pharmacists can play a role in both medical aids and regulation. But their social acceptance as a frontline patient care provider is necessary first. Similarly, in tele-healthcare, the professional pharmacist can play an essential role that has not been recognized yet due to lack of proper initiatives. We hope that policy makers of Bangladesh are aware of its potential and contribute to the wider promotion of tele-pharmacy services in the interest of the citizenry.

Acknowledgement

I’m thankful to Dr. Colin D. Rehm, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Epidemiology & Population Health, Alert Einstein College of Medicine, NY, USA for her precious time to review my literature and thoughtful suggestions. Also, I’m also grateful to seminar library of Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Dhaka and BANSDOC Library, Bangladesh for providing me books, journal and newsletters.

Figure 1: The Mapping of COVID-19 Confirmed Cases in BANGLADESH, 17 April 2020 (Source: IEDCR Web).

Citation: Mohiuddin AK (2020) Prospect of Tele-Pharmacists in Pandemic Situations: Bangladesh Perspective. Emerg Med Trauma. EMTCJ-100044