Evans Paul Kwame Ameade1*, Mohammed Mubarak Baba1, Negro Umar Iddrisu1, Anelly Abdulai Musah2, Stephen Yao Gbedema3

1Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, Tamale

2 Department of Nursing, School of Allied Health Sciences, University for Development Studies, Tamale

3Department of Herbal Medicine, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi

*Corresponding author: Evans Paul Kwame Ameade, Department of Pharmacology, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, P.O. Box TL 1350, Tamale.

Citation: Ameade EPK, Baba MM, Iddrisu NU, Musah AA, Gbedema SY (2018) Herbal Pharmacovigilance: Are Ghanaian Herbal Medicine Practitioners Equipped Enough to Assist in Monitoring the Safety of Herbal Medicines? - A Survey in Tamale, Ghana. Chronic Complement Altern Integra Med: CCAIM-101.

Received Date: 25 September, 2018; Accepted Date: 13 October, 2018; Published Date: 01 November, 2018

1. Abstract

Background: Despite the immense positive effect medicines have had on the life of humans, they also sometimes present adverse effects which affects the health of users. With herbal medicines playing immense role in the health of persons especially those in developing countries and an upsurge of patronage in even developed countries, there is urgent need for their safety to be monitored. Herbal medicine practitioners (HMPs) needs to play leading role in pharmacovigilance of these herbal products since some are known to cause adverse drug reactions (ADRs). An adverse drug reaction is a response to a medicine which is noxious and unintended, which occurs at doses normally used in man. HMPs can only be useful in monitoring safety of herbal medicines if they are knowledgeable about ADRs and pharmacovigilance hence the need to assess the knowledge of and attitude of HMPs in the Tamale metropolis towards pharmacovigilance.

Method: Using a semi-structured questionnaire, data was collected from 27 HMPs in a cross-sectional study in the Tamale metropolis. Microsoft excel and GraphPad Version 5.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego CA) were used to analyze the data to obtain frequencies, means and their standard deviations.

Results: Majority, 21 (77.8%) of HMPs acquired their knowledge and skill through apprenticeship. Herbal medicines having no or minimal harmful effect was the most stated reason, 16 (17.8%) why the HMPs recommend herbal medicines to their clients. Whereas 11 (64.7%) out of the 17 who said they knew what ADR is could completely or partially define it, only 3 (50%) of the 6 who ever heard of pharmacovigilance correctly stated what it is. The overall knowledge score of the respondents was 3.85/17 or 22.6%. The attitude score of 70.4% was recorded although only 2 (7.4%) had ever reported an incidence of ADR.

Conclusion: Although the knowledge of HMPs was poor, they had positive attitude towards ADR reporting. Despite their good attitude towards ADR reporting, less than a tenth had ever reported an incidence of ADR. There is an urgent need for national pharmacovigilance centers to involve HMPs in the pharmacovigilance of herbal products through provision of training on pharmacovigilance which would ensure the safety of the herbal medicines they prescribe or dispense.

2. Keywords: Adverse Drug Reaction; Attitude; Herbal; Pharmacovigilance; Practitioner; Reporting

3. Background

The science and the art of treatment and prevention of disease is pre-historic, and man’s relationship over time with plants has given the world enormous benefits. Written documents from many places all over the world including China, India and the Near East unequivocally showed that the use of medicinal plants as traditional remedies for numerous human diseases existed as far back as five millennia or better, it is as old as the existence of humans on earth [1]. According to the World Health Organization, (2004) Herbal Medicines (HM) include herbs, herbal materials, herbal preparations and finished herbal products [2]. Traditional medicine which in some countries is same as complementary or alternative medicine on the other hand is the sum total of the knowledge, skills and practices based on the theories, beliefs and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health and in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness [2]. For developing countries including those in Africa, traditional medicines continue to be used as the primary source of medicine with the WHO estimating a patronage level of up to 80% [3]. Even in developed countries, there is an increasing patronage of natural products such that in 2007, the out of pocket spending for natural products in the United State of America (USA) was US$14.8 billion [4]. Many factors may account for the use of traditional medicine including herbal medicine in developing countries. Some reason for the increasing use of herbal medicines include easy accessibility, availability, affordability, and also traditional medicines being firmly rooted in some religious and cultural practices of the people [3,5]. For developed countries, there are several reasons why their citizens still patronize traditional and complementary medicine despite their well-developed health systems available. For countries such as Singapore and Korea, the high patronage can be attributed to cultural and historical influences [5] however in many western developed countries the increasing use of complementary and alternative medicines can be attributed to concerns about the adverse effects of allopathic drugs. For persons with chronic diseases, Complementary and Alternative Medicines seem to be manage their conditions gentler than the allopathic medicines [3,5]. There is this notion among some users across the world that since herbal medicines are from natural sources, they are harmless or carry minimal risk [6,7]. This assumption that herbal medicines unlike the orthodox medicines are without adverse effect had been proven not to be accurate. For instance, Aristolochia fangchi which is used in preparing Chinese slimming tea had been found to contain Aristolochic acid which is nephrotoxic [8] while Hwang et al., (2012) also found Aristolchia manshuriens is used in eastern Asia for arthritis among other diseases to be genotoxic [9]. Ephedra sinica used widely as a weight reducing dietary supplement in the USA is associated with serious cardiovascular and central nervous system adverse effects [10,11]. Garlic (Allium sativum) used as food condiment and for the management of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia had been reported by Borreli et al, (2007) to exhibit various adverse effects including allergic reactions, changes in platelet function and coagulation [12]. During the development of allopathic medicines, an indispensable stage is the clinical trial during which useful adverse effects are identified. Some of the adverse effects attributed to these allopathic medicines were detected when they were being used by large populations through a formal process of drug safety monitoring known as pharmacovigilance. Pharmacovigilance (PV) is the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other possible drug-related problems [2]. Adverse drug reaction monitoring or surveillance can be classified into prospective and retrospective. For prospective ADR monitoring, patients prone to ADR or those given medicines which have high potential to cause ADR are monitored while retrospective monitoring is done by review of medical reports for ADRs [13]. Spontaneous reporting is the most effective method of drug safety monitoring which is a form of concurrent surveillance which involves health professionals such as physicians, pharmacists, nurses among others indicating suspected ADRs on standardized forms which are then sent to national pharmacovigilance centers where association between the drug and the effect is confirmed [13,14].The health and cost implications of adverse effects of allopathic medicines as reported in developed countries is enormous. In Singapore, ADR related hospital admissions were 12.4% [15] while the prevalence rate in the UK is 6.5% costing the health system an estimated £466 million [16]. With a prevalence rate of 4.2-30% in the United States of America, the cost of management and impact of ADRs is estimated at 30.1 billion dollars annually [17]. If the well-researched and tested allopathic medicines are found to be responsible for significant adverse effects and deaths, then harmful effects of herbal preparations could be enormous. Herbal pharmacovigilance is of great important such that the WHO is recommending to all countries to take steps to monitor herbal medicine and their related adverse effects [2]. There are however challenges with monitoring safety of herbal medicines. These include diversity of naming systems and difficulty in validating the botanical identity of the ingredients in herbal medicines which are be several unlike the single compounds in most allopathic medicines [18]. Even if the ingredients in a plant material are identified and quantified, several factors such as geographical source, plant part used, period and conditions of harvesting, as well as process of storage, process and extractions can all affect the qualitative and qualitative chemical profile of herbal medicines [18]. Despite these challenges poses by herbal medicines, there is the need for efforts to be made to monitor them considering the widespread patronage of this form of traditional medicine. However, training programmes on pharmacovigilance targets physician, dentists, pharmacists and nurses without involving herbal medicine practitioners [2]. For national pharmacovigilance centers to make gains in the reporting of herbal medicine induced ADRs, manufacturers, prescribers and dispensers of herbal medicine would have to be brought on board [2]. Effectiveness of spontaneous reporting of medicines is better achieved when health professionals are knowledgeable about ADRs and the reporting system [18]. To ascertain the preparedness of Ghanaian herbal medicine practitioners to play effective roles in herbal pharmacovigilance, it is imperative to measure their knowledge on adverse drug reaction and pharmacovigilance and their attitude towards pharmacovigilance which led to this study to be conducted in Tamale, the only city in northern Ghana.

4. Method

4.1. Informed Consent

At the start of the administration of the questionnaire, the HMPs were told in the language they best understand that they were not under any compulsion to participate in the study and that by collecting and completing the questionnaire or by participating in the interview they had given their consent to be part of the study. Similar information about consent was also provided in the introductory section of the questionnaire for those who are literates.

4.2. Ethics Approval

The Ethics Committee of the School of Medicine and Health Sciences of the University for Development Studies, Tamale, gave approval for this study.

4.3. Study Design and Setting

A cross-sectional study involving herbal medicine practitioners (HMPs) in the Tamale metropolis was conducted between 5th and 27th April, 2017.

4.4. Study Population

The list of HMPs was obtained from the northern regional office of the Traditional Medicine Practice Council office in Tamale. The HMPs were then contacted by telephone with a total of 35 of them confirming that they were practicing their profession in the Tamale metropolis. A total of five were involved in the piloting of the questionnaire and were therefore not included in the final data collection. Completed questionnaires were received from 27 of the 30 other HMPs who were eligible for the study.

4.5. Study Instrument

A self-administered semi-structured questionnaire was given to literate HMPs while a questionnaire guided face-to-face interview was applied to those who were not literates. Pretesting of the questionnaires ensured there was correction of ambiguous and inconsistent questions. The authors reviewed the questionnaire to ensure face validity of the data collecting tool. The 57 questions presented in the questionnaire consist of 34 closed ended with 23 opened ended ones. The questionnaire was divided into four sections: section A of the contained questions on the demographic characteristics of practitioners, section B on issue related to their practice of herbal medicine, section C focused on knowledge of herbal practitioners on adverse drug reactions and pharmacovigilance while section D of the contained questions about the attitude of herbal practitioners towards adverse drug reactions reporting.

4.6. Study Variable Measurements

Knowledge of the HMP on adverse drug reaction and pharmacovigilance was based on 17 questions. Depending on the level of effort required in answering the questions, knowledge questions were scored between 1 and 2 with wrong or ‘don’t know’ answer attracting no score. The overall knowledge score was 17. Respondents’ attitude towards ADR reporting was also assessed with 7 questions. Assessment of respondents’ attitude towards ADR reporting involved the use of a 5-points Likert score made up of strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, and strongly disagree. An option of ‘don’t know was also added. Scores for the Likert scale were strongly agree, 5; agree, 4; not sure, 3; disagree, 2; and strongly disagree, 1 for attitude questions “It is important to report any ADR; providing me with training on pharmacovigilance is appropriate; reporting ADR ensures patient safety; reporting ADR is my professional duty and reporting ADR should be compulsory”. However, the questions “All reported ADRs should be paid for and only serious and unexpected reactions should be reported” had strongly agree, agree, not sure, disagree and strongly disagree points allocated 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 scores respectively. ‘Don’t know’ response, scores 0.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Data was entered into Microsoft Excel, and analyzed using Graph Pad Prism, Version 5.01 (Graph Pad Software Inc., San Diego CA). Mean knowledge and attitude scores and their standard deviations were calculated.

5. Results

5.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics Of Respondents

Majority, 23 (85.2%) of the respondents were males, 17 (63.0%) practiced Islamic religion, 19 (70.4%) were married, 14 (51.9%) were between the ages of 30 and 39 years and 16 (59.3%) had tertiary level education. Most of them, 11(40.7%) grew up in towns in Ghana. Again, majority, 8 (61.5%, n =13) of respondents had obtained diploma as their highest level of educational qualification, 18 (66.7%) had practiced herbal medicine for less than 10 years and, 18 (66.7%) practice both prescribing and dispensing of herbal preparations to their clients. Just, 9 (33.3%) were involve in only dispensing of herbal products. Skills for the practice of herbal medicine was acquired by the majority, 21 (77.8%) through apprenticeship under a senior herbalist with only 1 (3.7%) trained formally as a medical herbalist in Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of respondents in this study.

5.2. Reasons for Herbal Medicine Practitioner Recommending Herbal Medicines

Table 2 shows the reasons why the herbal medicine practitioners would recommend herbal medicines to their patrons. The top six reasons were: No or minimal harmful effect, 16 (17.8%); more effective, 13 (14.4%); affordable, 13 (14.4%); accessible, 11 (12.2%); cures all diseases, 11 (12.2%) and no chemical components, 7 (7.8%).

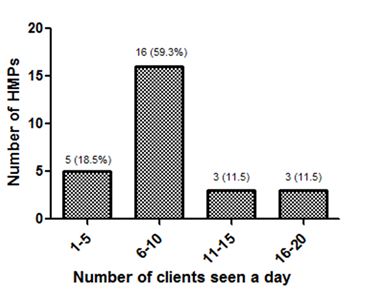

5.3. Number of Clients Attended to Daily by The HMPs

Majority, 16 (59.3%) of herbal medicine practitioners attend to between 6 and 10 clients in a day. Three (11.5%) HMPs attend to between 16 and 20 patients daily. The number of clients HMPs attend to daily is shown in figure 1.

5.4. Knowledge of Herbal Medicine Practitioners on Adverse Drug Reaction and Pharmacovigilance

Table 3 shows the assessment of the knowledge of the HMPs on adverse drug reactions and pharmacovigilance. Majority, 19 (70.4%) have heard of Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) but a lesser number of 17 (63.0%) stated they knew what ADR was. However, for those who claimed knowing what ADR was, 6 (25.3%) could not fully or partially define what it was. The score for the definition of ADR was just 0.556 out of 2 (27.8%). Majority, 19 (70.4%) did not know that ADR and Side effect (SE) were not the same and for those who said they are not same, majority, 5 (62.5%) could not clearly state the difference between ADR and SE. None of the respondents was able to state the number of types of ADR and only 1(3.7%) person was able to list a type of ADR. Majority, 16 (59.3%) said herbal medicines do not cause ADR. On pharmacovigilance, 7 (25.0%) have heard of it with 6 (22.2%) claimed to know what it is. Of those who said they knew what pharmacovigilance is, 3 (50%) could not explain the term. Only 1 (3.7%) knew that Sweden is the host of the international center for pharmacovigilance. Majority, 23 (85.2%) were not even aware of existence of a national center for pharmacovigilance in Ghana. For those who were aware of Ghana’s national center for pharmacovigilance, 2 (50.0%) did not know, it is the Food and Drugs Authority (FDA) of Ghana that coordinates issues on pharmacovigilance in Ghana. Majority, 17 (63.0%) did not know that ADR is a major cause of deaths across the world. Again, majority, 15 (55.6%) did not know that many ADRs are preventable. The mean knowledge score of the respondents about ADR and pharmacovigilance was 3.85±3.30 (22.6%).

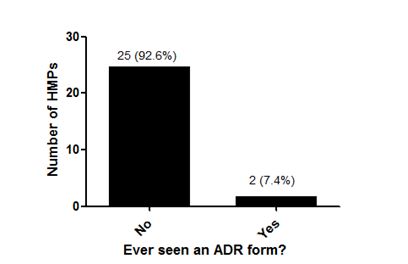

5.5. HMPs Ever Seeing an ADR Form

The possibility of respondents ever seeing an adverse drug reaction form is shown in figure 2. Majority, 25 (93.0%) of the HMPs had never seen an ADR form.

5.6. Training of HMPs on Pharmacovigilance and Reporting of ADRs

Majority, 25 (92.6%) of the respondent had never attended any training on pharmacovigilance with only 2 (7.4%) ever being trained at a workshop organized by Ghana FDA/WHO. Of the two that were trained, only 1 (50.0%) ever reported ADR since they were trained. Majority, 25 (92.6%) of the respondents had never reported any case of ADRs. Just 1 (3.7%) of the respondents ever verbally reported a case of ADR to the FDA. Majority, 16 (64.0%) of respondents did not state their reason for not reporting any ADR but 4 (16.0%) said they did not know where to report a case of ADR. The level of training of HMP on pharmacovigilance and their reporting of ADRs is shown in Table 4.

5.7. Types of Herbal Products Provided by Practitioners and Their Encounter with Side Effects

Majority, 24 (88.9%) of the HMPs dispensed prepackaged herbal medications, 2 (7.4%) dispense both prepackaged herbal medicine and raw plants while only 1 (3.7%) dispense raw plants materials. Majority, 22 (81.5%) believe that herbal medications have no side effects. Table 5 shows they types of herbal medicine products supplied by the herbal medicine practitioners and incidence of side effects.

5.8. Herbal Medicine Practitioners’ Attitude Towards Reporting of ADRs

Up to 10 (37%) of respondents strongly agreed that ADR reporting is important but the mean score was 70.4%. With a mean score of 80.0%, majority 17(63.0%) of respondents strongly agreed to being provided with training on pharmacovigilance. As to whether reporting ADRs should be paid for, majority 15(55.6%) of respondents were not sure with a mean score of 63.0% however, a greater proportion 14 (51.9%) of respondents agreed that ADR reporting should be compulsory with a mean score of 70.4%. With a mean score of 84.4%, most 13(48.1%) respondents strongly agreed that reporting ADR ensures patient safety. As to whether ADR reporting is a professional duty, only 6 (22.2%) strongly agreed but the mean score was 71.2%. The overall mean attitude score of the respondents towards ADR reporting was 3.52±0.78 (70.4%). Table 6 shows the attitude of herbal medicine practitioners towards ADR reporting.

6. Discussion

Medicines have been helpful in increasing lifespan and quality of life of humans but they can as well cause great discomfort and even death during their use. Since medicines can cause unpleasant effects on man, it is imperative that their safety is continually monitored through pharmacovigilance. This study found 81.5% of HMPs making the claim that herbal medicines have no adverse effect compared to between 74.3% and 85.8% reported in several other studies [19-21]. Again, in this study, the most important reason why HMPs recommend herbal medicines to clients was because they have no or minimal harmful effects. For such a high proportion of practitioners of the highly patronized herbal products to have this notion contrary to several reports of harmful effects of herbal medicines means much needs to be done to identify and manage safety issues related to the use of plant products for healthcare. What might have compounded the belief that herbal products are harmless is the lack of knowledge about ADRs and pharmacovigilance among practitioners of herbal medicine. The result from this study have proven that HMPs really lack knowledge of ADR and PV as they scored 3.85/17 or 22.6%. Similar studies in India among practitioner of Ayurveda also found them to possess poor knowledge of ADR and PV [20-22]. Whereas 38.2% respondents in the study by Bhanu et al., (2016), and 28.3% in Rajesh et al., (2016) both in India have heard of pharmacovigilance, this study recorded only 25.9% [20,21]. Again, whereas respondents in the study by Arun et al., (2015) in Odisha, India scored 41.2% and 36.5% respectively for the correct definition of ADR and PV, this study recorded 27.8% for ADR and 13.0% for PV [22]. The knowledge level of Ayurveda physicians seems higher than the HMPs in this study. This is understandable because the Ayurveda physician obtained graduate level Bachelor of Ayurvedic Medicine and Surgery in universities in India [23] but all the HMPs in this study except one hold a degree in Herbal medicine. During the training of the Ayurveda physicians they may have had some lessons in ADR and pharmacovigilance but probably was not enough to give them a better appreciation of drug safety monitoring. Some studies among conventionally trained health care professionals such as medical doctors, pharmacists, as well as nurses who had university level education also recorded inadequate knowledge of ADR. Oshikoya and Awobusuyi, (2009) reported inadequate knowledge about ADR among Nigerian doctors while Charles et al., (2017) found that except the pharmacist, other health care professionals including the doctors had less than 50% knowledge on pharmacovigilance [24,25]. Despite the low knowledge of HMPs on ADRs and PV, they have a positive attitude towards pharmacovigilance with a mean score of 70.4% which was better than the poor attitude found in studies by Bhanu et al., (2016) and Rajesh et al., (2016) among Ayurveda physicians [20,21]. Just as reported by Arun, et al., (2015) more than two-thirds of the HMPs were of the view that reporting of ADRs was necessary unlike the 12.5% reported in Rajesh et al., (2016) study [21,22]. Reporting of ADRs to National Pharmacovigilance Centres have been a challenge even for allopathic doctors [24,26,27] hence the 2 (7.4%) reported in this study and none in the studies by Arun et al., (2015), and Awodele, et al., (2013) as well as 0.8% reported by Rajesh et al., (2016) is not surprising [19,21,22]. How can healthcare professional report when they have not been trained on PV or seen ADR forms? In this study at least 2 (7.4%) of the HMPs have ever seen an ADR form which is better than the study by Arun et al., in which none of the Ayurveda physicians was familiar with an ADR form. For one out of the two who were trained on pharmacovigilance in this study to report a case of ADR to the FDA within 6 months of training shows that when healthcare professionals are trained, more spontaneous reports of ADR would be recorded. Level of training of HMPs by national pharmacovigilance centers is not encouraging across the world with Arun et al., (2015) and Rajesh et al., (2016) reporting 4.7% and 6.7% respectively [21,22]. This probably showed that NPCs across the world including Europe [18] do not recognize HMPs as ADR reporters. Majority of HMPs in this study attend to at most 10 clients a day, so would possibly attend to close to 3000 patrons in a year and such a number would have to be protected from the possible ADR by training the HMPs to pick up suspected cases of ADR for onward transmission of the information to the National Pharmacovigilance Centre in Ghana. With 96.3% of the HMP dispensing or prescribing pre-packaged herbal product means manufacturers of herbal products can also be trained on adverse drug reactions and pharmacovigilance so they can warn users of these products of possible adverse effects of their drugs. The limitation of this study is that it was carried out in Tamale and may not be representative of the whole country. With several of the respondents being illiterate or had only basic level education, there was the need for the investigators to interpret or explain some of the questions to them and this can invariably affect their responses. Despite these limitations, this study being the first among HMPs in Northern Ghana, should inform National Pharmacovigilance Centers to appreciate the need for some training on pharmacovigilance of this important healthcare personnel to they can assist in the monitoring of safety of herbal products which would continue to place valuable role in the health of ever-increasing number of patrons.

7. Conclusion

Knowledge of HMPs in Tamale on ADRs and pharmacovigilance is low but their attitude score of 70.4% can be considered as good. Majority of the HMPs had not been trained on pharmacovigilance and have never seen an ADR form which limits their ability to help in the monitoring the safe use of herbal products.

8. Acknowledgements

Authors wish to acknowledge the role the staff of the Traditional Medicine Practice Council office in Tamale, and all the herbal medicine practitioners who ensured the success of the study. I, Evans Paul Kwame Ameade (the lead author) affirm that I have listed persons or agencies who contributed significantly to this study to be named authors or acknowledge for their contribution.

9. Authors' Contributions

Conceived the idea, and analyzed the data: EPKA Developed the questionnaire, piloted it, collected the data, and were part of drafting of manuscript: EPKA MMB NUI AAM. Drafting of manuscript: SYG EPKA.

Figure 1: Number of clients the HMPs attend to daily.

Figure 2: Majority, 25 (93.0%) of the HMPs had never seen an ADR form.

|

Variable |

Subgroup |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Sex |

Male |

23 |

85.2 |

|

|

Female |

4 |

14.8 |

||

|

Religion |

Christianity |

9 |

33.3 |

|

|

Islam |

17 |

63.0 |

||

|

African Traditional Religion |

1 |

3.7 |

||

|

Where you grew up |

City |

7 |

25.9 |

|

|

Town |

11 |

40.7 |

||

|

Village |

9 |

33.3 |

||

|

Marital Status |

Single |

5 |

18.5 |

|

|

Married |

19 |

70.4 |

||

|

Divorced |

2 |

7.4 |

||

|

Widowed |

1 |

3.7 |

||

|

Level of Education |

No formal education |

4 |

7.4 |

|

|

Basic |

2 |

14.8 |

||

|

Secondary |

5 |

18.5 |

||

|

Tertiary |

16 |

59.3 |

||

|

Tertiary level certificates obtained (n = 13) |

Degree |

1 |

7.7 |

|

|

Diploma |

8 |

61.5 |

||

|

HND |

4 |

30.8 |

||

|

Age ranges (years) |

20-29 |

5 |

18.5 |

|

|

30-39 |

14 |

51.9 |

||

|

40-49 |

4 |

14.8 |

||

|

50-59 |

2 |

7.4 |

||

|

60-69 |

2 |

7.4 |

||

|

Number of years of practice |

< 10 |

18 |

66.7 |

|

|

10 - 20 |

5 |

18.5 |

||

|

> 20 |

3 |

11.1 |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Form of herbal practice |

Dispensing only |

9 |

33.3 |

|

|

Both dispensing and prescribing |

18 |

66.7 |

|

|

|

How was skill acquired? |

Workshop |

1 |

3.7 |

|

|

Herbalist |

21 |

77.8 |

|

|

|

Natural skill |

4 |

14.8 |

|

|

|

Went to school |

1 |

3.7 |

|

|

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents.

|

Reason for recommending herbal medicines to clients |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

No or less harmful effects |

16 |

17.8 |

|

Affordable |

13 |

14.4 |

|

More effective than orthodox medicines |

13 |

14.4 |

|

Accessible |

11 |

12.2 |

|

Cures all diseases |

11 |

12.2 |

|

No chemical components |

7 |

7.8 |

|

Others |

6 |

6.7 |

|

It is natural |

3 |

3.3 |

|

Convenient to use |

2 |

2.2 |

|

Does not expire |

2 |

2.2 |

|

Easy to prepare |

2 |

2.2 |

|

It is a heritage |

2 |

2.2 |

|

No addiction |

2 |

2.2 |

Table 2: Reasons why herbal medicine practitioners recommend herbal medicine to their clients.

|

Variable |

Subgroup |

Number of respondents |

Mean knowledge score (%) |

|

Ever heard of ADR (1) |

Yes |

19 (70.4%) |

0.704±0.465 (70.4%) |

|

No |

8 (29.6%) |

||

|

Know what ADR is? |

Yes |

17 (63.0%) |

Not scored |

|

No |

10 (27.0%) |

||

|

Definition ADR1 (2) |

Correct * |

11 (64.7%) |

0.556±0.751 (27.8%) |

|

Incorrect |

6 (25.3%) |

||

|

Is ADR same as Side effect (1) |

Yes |

10 (37.1%) |

0.296±0.465 (29.6%) |

|

Noc |

8 (29.6%) |

||

|

Don’t know |

9 (33.3%) |

||

|

If ADR is not same as SE, what is the difference.2 (1) |

Correct |

3 (37.5%) |

0.111±0.320 (11.1%) |

|

Incorrect |

5 (62.5%) |

||

|

How many types of ADRs exist3 (1) |

Correct |

0 (0.0%) |

0.000 (0.0%) |

|

Incorrect |

27 (100.0%) |

||

|

Name and explain any type of ADR4 (2) |

Correct |

1 (3.7%) |

0.037±0.192 (3.7%) |

|

Incorrect |

26 (96.3%) |

||

|

Herbal medicines can cause ADR (1) |

Yesc |

11 (40.7%) |

0.407±0.501 (40.7%) |

|

No |

16 (59.3%) |

||

|

Ever heard of Pharmacovigilance? (1) |

Yes |

7 (25.9%) |

0.259±0.447 (25.9%) |

|

No |

20 (74.1%) |

||

|

Do you know what pharmacovigilance is? |

Yes |

6 (22.2%) |

Not scored |

|

No |

21 (77.8%) |

||

|

What is pharmacovigilance if you stated you knew what it is?5 (2), (n = 6) |

Correct |

3 (50%) |

0.259±0.656 (13.0%) |

|

Incorrect |

3 (50%) |

||

|

Which country/city hosts the international centre for pharmacovigilance?6 (1) |

Correct |

1 (3.7%) |

0.037±0.192 (3.7%) |

|

Incorrect |

26 (96.3%) |

||

|

Are you aware of a national centre for pharmacovigilance? |

Yes |

4 (14.8%) |

Not scored |

|

No |

23 (85.2%) |

||

|

Agency responsible for pharmacovigilance in Ghana?7(1) |

Correct |

2 (50.0%) |

0.074±0.267 (7.4%) |

|

Incorrect |

2 (50.0%) |

||

|

Where can one report ADR in Tamale?8 (1) |

Correct |

8 (29.6%) |

0.296±0.465 (29.6%) |

|

Incorrect |

19 (70.4%) |

||

|

ADR is a major cause of deaths across the world (1) |

Yesc |

10 (37.0%) |

0.370± .492 (37.0%) |

|

No |

17 (63.0%) |

||

|

Many ADRs are preventable (1) |

Yesc |

12 (44.4%) |

0.444±0.506 (44.4%) |

|

No |

15 (55.6%) |

||

|

Total (17) |

|

|

3.85±3.30 (22.6%) |

|

1An adverse drug reaction is a response to a medicine which is noxious and unintended, which occurs at doses normally used in man. 2Side Effect is related to the pharmacological properties of the drug and can sometimes be beneficial but ADR is always harmful or noxious. 3Six types of ADR. 4Type A (Augmented) -Predictable reaction related to the pharmacologic action of the drug - exaggerated pharmacologic response; Type B (Bizzare) - Unpredictable reaction not related to the pharmacologic action of the drug; Type C (Chronic)- Uncommon reaction related to the cumulative dose of a drug.; Type D (Delayed) - A usually dose related reaction which occurs or becomes apparent sometime after the use of the drug; Type E (End of Use); Adverse reaction which occurs soon after the withdrawal of the drug; Type F (Failure); Drug reactions occurring as a result of drug-drug interaction. 5Pharmacovigilance is the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects of drugs or any other possible drug-related problems. 6Uppsala/Sweden. 7Food and Drugs Authority. 8Food and Drug Authority office/Community pharmacies/Hospital, etc. c =Indicates the correct answers. |

|||

Table 3: Knowledge of herbal medicine practitioners on Adverse Drug Reaction and Pharmacovigilance.

|

Variable |

Subgroup |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

Have you ever reported ADR? |

Yes |

2 |

7.4 |

|

No |

25 |

92.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Why didn’t you report ADR? |

Reasons not stated |

16 |

64.0 |

|

No case of ADR |

2 |

8.0 |

|

|

Don’t know who to report to. |

4 |

16.0 |

|

|

ADR not life threatening |

2 |

8.0 |

|

|

Had no idea of ADR |

1 |

4.0 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Have you ever attended any training on pharmacovigilance |

Yes |

2 |

7.4 |

|

No |

25 |

92.6 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ever since you were trained have you ever reported ADRs? |

Yes |

1 |

50.0 |

|

No |

1 |

50.0 |

Table 4: Training of HMPs on pharmacovigilance and their reporting of ADRs.

|

Variable |

Subgroup |

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

What type of herbal medication do you mostly dispense? |

Prepacked herbal medications |

24 |

88.9% |

|

Prepacked herbal medicine and raw plants |

2 |

7.4% |

|

|

Raw plants |

1 |

3.7% |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Does any of your HM have side effects? |

Yes |

5 |

18.5% |

|

No |

22 |

81.5% |

Table 5: Forms of herbal products supplied by Herbal medicine practitioners and their side effects.

|

Variable |

Responses |

Mean score (%) |

|||||

|

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Not Sure |

Disagree |

Strongly Disagree |

Don’t Know |

||

|

It is important to report any ADR.

|

10 (37.0%) |

8 (29.6%) |

3 (11.1%) |

2(7.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (14.8%) |

3.52±1.74 (70.4%) |

|

Providing me with training on pharmacovigilance is appropriate. |

17 (63.0%) |

5 (18.5%) |

1 (3.7%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

4 (14.8%) |

4.00±1.78 (80.0%) |

|

2 (7.4%) |

7 (25.9%) |

15 (55.6%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (7.4%) |

1 (3.7%) |

3.15±1.10 (63.0%) |

|

|

4 (14.8%) |

14 (51.9%) |

5 (18.5%) |

2 (7.4%) |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (7.4%) |

3.52±1.28 (70.4%) |

|

|

1 (3.7%) |

8 (29.6%) |

4 (14.8%) |

9 (33.3%) |

4 (14.8%) |

1 (3.7%) |

2.63±1.28 (52.6%) |

|

|

13 (48.1%) |

10 (37.0%) |

3 (11.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (3.7%) |

4.22±1.09 (84.4%) |

|

|

6 (22.2%) |

9 (33.3%) |

8 (29.6%) |

3 (11.1%) |

0 (0.0%) |

1 (3.7%) |

3.56±1.19 (71.2%) |

|

|

Overall attitude score |

|

|

|

|

|

|

3.52±0.78 (70.4%) |

Table 6: Herbal medicine practitioners’ attitude towards reporting of ADRs.

Citation: Ameade EPK, Baba MM, Iddrisu NU, Musah AA, Gbedema SY (2018) Herbal Pharmacovigilance: Are Ghanaian Herbal Medicine Practitioners Equipped Enough to Assist in Monitoring the Safety of Herbal Medicines? - A Survey in Tamale, Ghana. Chronic Complement Altern Integra Med: CCAIM-101.