International Journal of Education Advancement

Review Article

The Academic Studies between Printed and Multimedia Text in Italy

Patrizia Sposetti*

Department of Social and Developmental Psychology, "Sapienza" University of Rome, Italy

*Corresponding author: Patrizia Sposetti, Department of Social and Developmental Psychology, "Sapienza" University of Rome, Piazzale Aldo Moro, 5, 00185 Roma RM, Italy, Tel: +390649910789, Email: patrizia.sposetti@uniroma1.it

Citation: Sposetti P (2020) The Academic Studies between Printed and Multimedia Text in Italy. Int J Educ Adv: IJEA-100001

Received date: 23 January, 2020; Accepted date: 10 February, 2020; Publication date: 12 February, 2020

Introduction

This essay falls within the reflection on the relation between learning places and methods and the use of new technologies in Italy. The diffusion and immediate availability of texts and sources of information through the Internet have enabled the access to various databases of texts as well as to several types of documentation, thus increasing the time spent on reading [1]. Moreover, the Internet-intended as a source of information -plays a crucial role within the education and training systems. In Italy, Law 107/2015 of the Ministry of Education, Universities and Research (MIUR) has provided for a National Plan for Digital Education (PNSD) which promotes the dematerialization of books with in the school system, often regarded as proven educational instruments.

However this process necessarily involves some risks. As evidenced by Casati (2013) [2], printed books have clear cognitive advantages thanks to their linearity, the stability of the page bearing the contents, and the ease of reading. This could be supplemented by critical elements relating to the research on the Internet [3] and the difficulty of selecting the sources and the information highlighted by the research. In this context, the issue is developed also based on the evidences arisen from the interviews with some students about to graduate in Education and Training (SEF) - 1st level degree - at The Sapienza University of Rome.

Internet, study and reading- A complex network

The diffusion of the Internet has strongly influenced our habits as well as the learning and reading places and methods. The learning contexts and the school areas have undergone major changes as a result of the introduction of technologies, [4,5] as happens, more generally, with reading habits. However, stating that “Printed books will surely disappear due to the freely available resources on the Internet; encyclopaedias, atlases, and even dictionaries will become useless, and the traditional lectures will be replaced by multimedia materials” [6], sounds like a loose assertion, especially considering the results of the surveys on the relation between the use of the media and the reading performance. Since the Nineties [7], but especially in recent times, the empirical research has increasingly dealt with the cognitive aspects of reading relating to both printed and multimedia texts [8] The results are not univocal and can be summarised through three difference categories: zero (1), positive (2) and negative (3) Actually, some researches show a negligible difference - or no difference at all- in terms of comprehension between printed texts or e-books [9,10]; whereas, according to other studies, reading e-books facilitates the comprehension [11,12]. A third series of studies includes analyses and reflections leading to the opposite conclusion with respect to the previous categories [2] Various researches prove that - especially in case of long or complex texts such as the narrative or argumentative ones - e-books seem to impair the comprehension process [13-17] with a remarkable impact also on the emotional sphere and the ability to "enter" the text [18].

Furthermore, the growing and quick development of the Internet both worldwide and in Italy has had and still has a positive influence on the access to texts and information, however we should also consider that the actual exploitation of the potential of the media features some criticalities1. Especially in Italy, the data regularly collected through the Audiweb monitoring throughout the national territory show that a widespread diffusion and use of the Internet do not necessarily correspond to an equally large access to online information2. In particular, the data indicate that the availability of media and the presence of the required technological prerequisites do not guarantee their effective and regular use. This aspect is also evidenced by an exhaustive report on the promotion of reading in Italy, which was published in 20133. The most striking feature is the low correlation between the ownership of tablets and the reading of e-books, thus confirming that the use of the Internet forces us to read, but does not automatically turn those who read e-books into persons able to read complex texts for learning or research purposes.

The Digital Education in Italy

Nowadays, in the Italian school system, the digital education and the diffusion of technological devices is a core issue of the relevant policies and reforms, to the extent that in the last decade the MIUR has introduced a National Plan for Digital Education (PNSD), which is currently one of the basic pillars of Law no. 107 of 2015, the so-called "Buona Scuola" and provides “an operational overview that reflects the Government's position on the major innovation challenges within the public sphere: the main issues are the innovation of the school system and the opportunities for digital education” (page 14).

Thanks to the PNSD various actions were promoted from 2008 to 2012 in order to spread digital technologies and reach an increasing number of students, regardless of the disciplines4. In 2013/2014, the "Wi-fi" and "Poli formativi" initiatives fostered the digitisation process also through the use of resources provided by the 2007-2013 EU national operational programming (PON Education) in four regions (Campania, Calabria, Sicily and Apulia). Eventually, the data collected during the 2014-2015 survey and kept at the MIUR Technology Observatory show a remarkable progress towards the dematerialization and digitisation of the services within the school system (page 18.)With specific reference to the teaching activity, the PNSD highlights the necessity to develop the computer literacy and skills of students and the training of teachers, in order for the latter to act as "promoters of innovative learning paths" (page 29). However, in my opinion, the document does not clearly indicate how these objectives can be achieved and how students can become both "aware users of digital technologies and devices" and "producers, creators and designers." The document that establishes the so-called "Scuola 3.0" focuses on crucial objectives, however words like “texts”, “research”, “reading”-i.e. words referring to the operational skills to be developed - are surprisingly missing. The fact that the text forms and the reading methods are largely diversified and depend on the device used in the digital environment urges the users to acquire specific study and research skills, including the ability to select the sources, plan the researches, process the information and use the Internet in an targeted way. This applies also to hypertexts: “The comprehension of a hypertext implies a constant research, assessment, construction and reassembly of the text. Readers should have cognitive, emotional and meta cognitive skills (to select, assess the relevance and the reliability of the sources), together with suitable predictive skills (to assume the destination of a link and the navigation path), greater inferential skills (to mutually connect the various aspects of a piece of information in a consistent and meaningful manner), selective strategies and a high self-regulatory control (to reduce the information overload) [19,20].

In my opinion, advanced and cutting-edge technological equipment is not enough to achieve these targets; it is necessary to develop an accurate teaching program, which requires a constant support to teachers and schools as well as appropriate investments in training. The replacement of traditional blackboards with the LIMs and of printed texts with e-books, together with the introduction of computers into the classrooms - an objective which has not been accomplished yet in Italy - are not enough to improve the study and research skills.

A survey on the use of the Internet for the drafting the final dissertation for the 1st-level degree

Obviously, today researches and studies must necessarily be accompanied by an aware use of the Internet. As already evidenced, this competence cannot be taken for granted among the average users of the Internet and is the subject of reflections within the school system. At academic level, the acquisition of advanced skills by those students who are about to graduate is - or should be-taken for granted: actually, the drafting of the final dissertation requires the ability to find and organize the information also through the web. A student about to graduate is a researcher and his/her admission into the world of the experts passes necessarily through the drafting of a final dissertation. In order to get an insight into this issue, I have carried out a survey and interviewed 5 students about to graduate in "General Didactics", 1 in "Social pedagogy" of the 1st-level degree course in Education and Training (SEF), and 1 in Pedagogy, Education and Training (PSEF), 2nd-level degree course at the at The Sapienza University of Rome. I personally followed all the final dissertations as either a coordinator (6) or an advisor (1). The interviews were collected in June 2017, namely two weeks before the presentation of the dissertation and then after the end of the drafting process. The interviewees had completed their studies within the deadlines relating to their course. These students-researchers were asked to reflect on the different ways and purposes of the use of printed texts as well as of the Internet for the research activities required by the drafting of their dissertation. In particular, I asked them to tell me how they used the Internet and/or printed texts for their dissertation; how they chose the sources, especially in case of quotes.

The first element - partly unexpected - highlighted by the interviews is the use of printed texts and the Internet to develop and write the dissertation. Most of the interviewees stated that they had mainly consulted printed texts, limiting the Internet to a less frequent or even negligible use. Then they were asked to indicate this percentage ratio to obtain a net estimate: four students said that their information sources consisted of 70% printed texts and 30% texts found on the Internet; in two cases, the use of Internet (I) was negligible (5% <I <10%); while in another case it equally corresponded to the use of printed texts (50%). To confirm the limited consultation of electronic sources, none of these students had drafted a sitography, since they simply added the reference to the few websites visited or documents downloaded within the text. Therefore, based on the interviewees, printed texts are still the main source used for the drafting of the final dissertation.

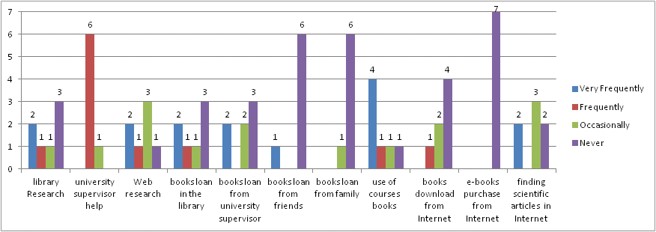

In their opinion, the texts found on the Internet are updated and/or simpler and clearer, since the Internet provides explanations and simplifications of models and assumptions. The web is also regarded as a useful means for the access to important resources such as online dictionaries or databases. In spite of the widespread use of printed sources, libraries were little attended or even neglected by more than half of the group. For this phenomenon there are two reasons mutually connected. The first is the role played the expert (coordinator or advisor), who represents the main access to the information sources, by suggesting the consultation of some texts or sometimes lending the same texts; the second is the fact that the study books are the prevailing source. Considering this general orientation, libraries - if attended -are places where printed texts can be lent, while the Internet is a place for general online researches and reading and is also used to download books (1) or articles (2) but never to purchase e-books (Table 1).

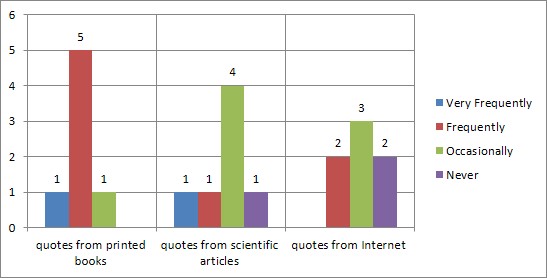

Another interesting aspect is the use and value of quotes, which provide a significant example of the analysis of scientific texts. In research and scientific texts, in fact, the reported speech, both direct and indirect, implies the use of the sources and suggests the ability to manage the same sources and master the specific knowledge which underlies the drafting of a scientific academic text. According to the students, the Internet which was poorly used as an information source helps collect the quotes from various websites. Despite the limited use of the Internet for research purposes, and compared with the consultation of printed texts, the interviewees stated that they did not use direct quotes taken from the source only in two cases. The quotes from printed books were used in almost all the dissertations of the group subjects; while quotes from scientific articles were rarely present (Table 2).

Discussion of the results

According to the students interviewed, the learning and reading process relies on the use of printed texts and the aware use of the web is still limited. The group has generally opted for printed texts although some interviewees stated that they had used the Internet to find further and clearer information. Therefore, between the abstract assumptions and the actions of the students there seems to be a partial gap which, in my opinion, is partly due to the concept of autonomous learning. The students’ declarations, in fact, show a certain dependence on the experts -i.e., in this case, the professors acting as coordinators, advisors and the main source of information. Professors are often preferred over the libraries, which are largely neglected, and may orient the search for texts. Moreover, the drafting of the dissertation for the 1st-level degree is the natural continuation/conclusion of the academic career, and the interviewees precisely stress this aspect. The almost total absence of quotes from scientific articles -except for one student - is a major problem. As researchers surely know, the consultation of articles is crucial, since they provide the most recent and updated research results in spite of the constant progress within the discipline. The Internet is necessary to easily and quickly access to this knowledge; however only two students said that they had used the web for this purpose. Therefore, the great potential of the network for study and research purposes is not being exploited yet.

Thus, from an educational point of view, it is necessary to raise awareness on the potential of this instrument. This applies also to the student of the 2nd-level degree course, whose answers were similar to those provided by her colleagues of the 1st-level degree course.

Conclusions

The data collected during the interviews confirm the effectiveness of a didactic approach aimed at promoting the acquisition of the skills necessary for an advanced and aware use of the digital information contents and forms, even at academic level, with special reference to the complex texts. In order to turn students into active users of the Internet, we submit some proposals: the choice of the contents in the digital texts, the removal of any obstacle to attention, time scheduling, learning and memorisation strategies, the analysis of the effects exerted by the reading of printed and digital texts on the comprehension, the relation between printed texts and the Internet. These issues may lay the foundations for future educational activities according to the principles of progressivity and continuity [21].

Table 1: Students activities

Table 2: Use of quotes

Citation: Sposetti P (2020) The Academic Studies between Printed and Multimedia Text in Italy. Int J Educ Adv: IJEA-100001