International Journal of Education Advancement

Research Article

Social Entrepreneurship: An Approach to Education in Entrepreneurship in Mexico

Cárcamo-Solís ML1*, Serrano-Torres MG2, Acevedo-Arcila IA3 and López-Lemus JA4

1PhD. Social and Politics Sciences, University of Guanajuato, Mexico

2PhD. Administration, Professor in University of University of Guanajuato, México

3Student of Master’s Degree in Technology Management in University of Guanajuato, Mexico

4PhD. Organizational Studies and Administration, in University of Guanajuato, Mexico

*Corresponding author: María de Lourdes Cárcamo-Solís, PhD. Social and Politics Sciences, University of Guanajuato, Mexico.

Citation: Cárcamo-Solís ML, Serrano-Torres MG, Acevedo-Arcila IA, López-Lemus JA (2020) Social Entrepreneurship: An Approach to Education in Entrepreneurship in Mexico. Int J EducAdv: IJEA-100004

Received date: 08 January, 2020; Accepted date:16 January, 2020; Published date: 24 January, 2020

Abstract

The objective of this study is to quantitatively analyse the results of the entrepreneurship sub programme created by the Foundation of Higher Education-Enterprise (FESE), “My First Enterprise: Start a Business by Playing”. The goal of this sub programme is to establish the conditions for the gestation of future entrepreneurs from basic institutions and higher education institutions by creating 1327 mini-companies, in 27 entities in Mexico, to generate opportunities for self-employment in the long term, lower unemployment and sharing knowledge, values and skills in Mexico. The structural equation model demonstrates the results of the social entrepreneurship of the FESE programme through entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship education has taken a strong turn in recent years, especially for developing countries, considering that entrepreneurship promotes skills, attitudes and values to develop competencies for the individual to take initiatives that promote change.

The main findings are as follows:

The creation of a microbusiness is based on values, attitudes and knowledge.

Training, the business plan and its administration are critical in social entrepreneurship.

“My First Enterprise: Start a Business by Playing” is programme that encourages the opening of micro-companies.

Keywords: College; Lucrative entrepreneurship; Micro-businesses; Primary school students; Social entrepreneurship

Introduction

Social entrepreneurship is an area with high potential due to the increased intellectual interest in this topic, linking several areas of knowledge such as management, entrepreneurship, public policy, sociology, and other areas of the social sciences [1]. The Foundation of Higher Education-Enterprise (FESE), a non-governmental organization (NGO) founded at the beginning of the new millennium in Mexico City, Mexico, is part of civil society and coordinates the economic, human, talent and entrepreneurial resources of social institutions [2], with the aim of creating social value [3-6] by developing the knowledge, values and attitudes toward entrepreneurship derived from a group of primary school children and young professionals from vocational schools.

The above enterprise is focused on the development of micro-signatures among students from fourth to sixth grade of primary school in 27 entities of the Mexican Republic, who are advised by counsellors (students of administration and related careers) who reaffirm their knowledge of entrepreneurial philosophy when transferring such philosophy to these students of primary education. The main conclusion is that the FESE was motivated to create this entrepreneurship programme to combat the unemployment generated by the global financial crisis (2007-2008), through education focused on the formation of micro-businesses, which promise in the long term to improve the status of socio-economically poor communities in Mexico [7].

Theoretical framework

According to [4,5] the entrepreneur is the one who buys products or manufactures products at a certain price; once the costs are determined in the present, he/she correctly combines them to obtain a new product and then sells the product at uncertain prices in the future. In this sense, the lucrative entrepreneur does not have a safety net and must assume the risks and uncertainty present in the market. Therefore, this author manages the uncertainty of innovating at a price and obtaining an uncertain profit by selling the product in the future.

Regarding the definition of entrepreneurship, we refer to [6] a pioneer in the concept of entrepreneurship. He determines within his theoretical model that "the real function of an entrepreneur is to take initiatives, to create", which provides the individual with the opportunity to take advantage of the environment, without the ideas necessarily being produced by him/her.

The phenomenon of entrepreneurship, the name of which comes from the Anglo-Saxon term "entrepreneurship", is an area of growing development in the field of scientific research. Academic interest in entrepreneurship is based on evidence about its contribution to economic growth, the rejuvenation of the socio-productive fabric, the relaunching of regional spaces, the revitalization of innovative process and the generation of new jobs [8].

According to [9], the entrepreneur detects opportunities and acts to take advantage of them to the degree that he/she learns to develop skills to take advantage of market imperfections. The lucrative venture consists of the implementation of a business idea with the aim of generating resources, wealth or benefits to improve the family, local or regional economy.

The role of entrepreneurship related to economic development has been recognized by several important theorists [10-15]. In summary, these authors agree with the concept of entrepreneurship, which has always referred to attitudes towards the environment and its response capacity in the sense of building solutions that add value to society. According to the European Union (2012), entrepreneurship is based on an individual's ability to turn ideas into action; this ability is related to creativity, innovation and risk taking, as well as to planning and risk management to achieve objectives [16] also argue that entrepreneurial behaviour is generally used when referring to the best business skills needed to face changes and uncertainty in the future. The above authors also state that the attributes linked to entrepreneurial activity are high availability for change, self-confidence, creativity and innovation aimed at solving problems [17].

The idea of innovation has been constantly related to different aspects of entrepreneurship: in the development of economies, in the long term, economic growth will increase the creation of businesses and, as a result, generate innovation in terms of products, services and processes. The innovation process is closely related to the concept of an enterprise because its creation is itself an innovation of a social nature, as targets are pursued to limit social exclusion [18]. However, the intensity of innovation differs depending on the companies that are being created; organizations are motivated to generate value by innovating, increasing their competitiveness and promoting profitability [19,20].

Faced with the growing unemployment worldwide, caused by adjustments in the economic policies of governments, technological advances or market imperfections, lucrative entrepreneurship has emerged as one of the main alternatives that generate economic resources. In this sense, entrepreneurship education beginning in primary school is central to sowing the entrepreneurial spirit from an early age; this knowledge and fundamental learning that will define the learners’ personalities is based on playful learning by doing -learning by doing- which allows 90% of the knowledge to be acquired in this way and the remaining 10% of the knowledge to be a result of the study of the related theory [21].

There are also other theoretical positions on entrepreneurship education: 1) cognitive theory, 2) the theory of reasoned action, and 3) the theory of planned behaviour. Cognitive theory assumes that entrepreneurs possess a knowledge structure that they use to make assessments, judgements or decisions involving assessing opportunities, business creation and their own growth [22].

The theory of reasoned action considers that action in people is, in large part, based on rational states, systemically using the information available to make an evaluative judgement about its implications. In essence, this theory conceptualizes intention as a precursor to action, although it does not pretend to establish what intention always leads to action; intention and action do not have a perfect correspondence [23].

Following up on and complementing the reasoned theory is the theory of planned behaviour, according to the proposal of [24], who reviews the theory of reasoned action, maintaining attitude and the subjective norm as the essential elements for entrepreneurial action but adding perceived control, forming a more complete theory, which corrects the previous limitations on behaviour and lack of control.

According to recent research, successful entrepreneurs, compared to managers, tend to be more aware, more open to new experiences, less neurotic and more friendly or pleasant [25]. In addition, successful entrepreneurs are more persistent, hardworking and organized and have a greater desire for success and a higher degree of responsibility than managers [26-30].

The particular challenge that entrepreneurship education faces is to be able to turn ideas into action. Traditional methods, such as reading, literature reviews, exams, among others, do not activate entrepreneurship [31]. One study found that such methods even inhibit the development of entrepreneurial attitudes and competencies [32].

In a world full of economic needs, lucrative entrepreneurship has emerged as an alternative for the generation of economic resources, hence the importance of education in lucrative entrepreneurship in primary school children. Children are then educated and use the right hemispheres of their brains to begin playing a game: sleeping, resting, being in the shower, and singing; thus, the child visualizes an idea, a business opportunity, and therefore, where there is a need or difficulty, a business opportunity arises that in turn generates a gain.

A lucrative venture has the task of improving the economic situation of an individual, a family, a city, a country and the entire world. For this, we need to pursue profitable and effective ideas that promote productivity and turn a profit to obtain good results, which is synonymous with the venture for profit.

It is very important to mention that in Mexico, the National Association of Universities and Institutions of Higher Education (ANUIES) and the FESE try to provide basic knowledge to children through projects to create a company, which is expected to help the children learn about behaviour and entrepreneurial culture. Such projects have been shown to be effective in demonstrating that children are capable of acquiring and applying theoretical knowledge about entrepreneurship [33]. Outside the country, Mexico has formed business accelerators (Business Technology Accelerators), with the objective of promoting its internationalization of trade [34].

At the same time, it should be clarified that according to the analysis conducted by Herrera and Yong (2004), countries such as Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, Mexico and the Dominican Republic have made few educational efforts compared to other countries such as Colombia or Brazil, and thus, the former countries have observed deficiencies in their curricular design in essential elements in entrepreneurial behaviour, such as responsibility, autonomy, teamwork, adaptability, resource management, social networks, risk taking and learning about entrepreneurship.

Indeed, entrepreneurial education has taken priority in primary, secondary, and preparatory schools and universities [35], and in some studies, a significant relationship has been found between entrepreneurial programmes and entrepreneurial intention in students [36-40].

Mexico has very few proposals for the didactic inclusion of entrepreneurial education in its curricula [41], although it has recently been in the process of improvement. A programme created to face this situation, "My First Enterprise: Starting a Business by Playing", by the National Association of Universities and Institutions of Higher Education (ANUIES) and the FESE, started in 2009, has provided basic knowledge to children through a subproject to create a company, which is expected to help these students to learn about entrepreneurial behaviour and culture, showing its effectiveness in transferring them into small entrepreneurs [41].

This program by the FESE is critical since it promotes entrepreneurial education in times of great difficulty, such as those that our country has gone through. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEGI), Mexico has had an average unemployment rate from 1982 to 2018 of 4%, although with rates higher than 5% from 2009 to 2012, which has led to greater entrepreneurship, generating different work schemes: 96.6% of the total employed personnel depend on the sustainability or creation of companies, with 68.4% being distributed as employees, 22.5% as freelancers, 4.41% as entrepreneurs in businesses and family plots, and 4.7% as employers. Faced with these economic needs, lucrative entrepreneurship is considered the main engine of the economy to promote education in lucrative entrepreneurship, the task of which is to improve the economic situation of a person, family, city, country and the whole world. For this, we need ideas that boost productivity and profitability and that have good economic benefits, obtaining profits to help reproduce the business.

An important and diverse range of examples of child entrepreneurship now exist. According to Universia (2018), there are innumerable success stories in children who have and were successful in lucrative entrepreneurship. Below are 25 cases of entrepreneur children, which show that the best stage to start an endeavour is in childhood, and there is a high probability that in the future, the entrepreneurial attitude will be maintained by all the skills, knowledge, attitudes and impacts that are generated from entrepreneurial education (Table 1).

Description of the educational sub programme to promote entrepreneurship in young students

The FESE (2014) is part of civil society and orchestrates the economic and human resources, talent and entrepreneurial spirit of social institutions with the aim of creating social value [42] by preparing knowledge, values and attitudes towards entrepreneurship derived from a group of primary school children and young professionals of vocational school. Entrepreneurship is focused on the development of micro-businesses by children from fourth to sixth grade of primary education institutions (IEB) in 27 states of the Mexican Republic, who are tutored by counsellors, who are students of administration or related careers of institutions of higher education (IES), who reaffirm their own entrepreneurial knowledge and spirit by preaching their knowledge to these children. The main intention of the FESE was to create the entrepreneurship programme to combat the unemployment generated by the global financial crisis (2007-2008), through education focused on the formation of micro-businesses, which promise in the long term to improve the status of socio-economically poor communities in Mexico¨[7].

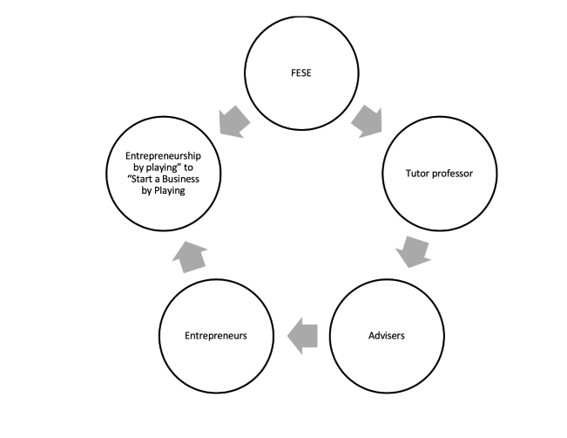

The sub programme, "My First Enterprise: Start a Business by Playing", focused on the following stages: a) a period of training the tutors and advisers or consultants, b) the development of new businesses with assistance from an advisory group, and c) the opening of mini-companies through the sub programme (Figure 1).

The FESE promoted a training course in entrepreneurial skills via email for the tutors of the HEIs who carried out various exercises and tasks to reinforce their knowledge about the incubation of small businesses with the remote support of an FESE expert in the area of entrepreneurship. The tutors interacted with other tutors from the interior of the Mexican Republic through social networks to share ideas, criticisms and feedback on how to transfer knowledge in the creation of new small businesses. Afterwards, the tutors trained the counsellors-students with undergraduate degrees in administration, business management and related areas of the IES-through a course on how to develop entrepreneurial action in students from 4 to 6 IEB degrees. With this process, the IES students reinforced knowledge on how to incubate small businesses in primary school children. The tutors highlighted the important role they had as advisors in helping to awaken the entrepreneurial spirit and create and/or reaffirm values and entrepreneurial skills. The course ended with an exam to ensure that all counsellors had acquired the necessary administrative knowledge for management and the skills to open small businesses.

Subsequently, tutors and counsellors of the IES agree to select the IEB to choose small entrepreneurs of an elementary school. First, establish an agreement signed between the tutor and advisers of the IES and the director of the IEB to start the subproject. This agreement was proposed by the FESE, with the following rules: 1) the FESE together with the corresponding IES will provide the seed capital (from 1500 to 3000 Mexican pesos) to the entrepreneurs forming small companies, as well as the scholarships of the tutor (single payment of $ 10,000.00 Mexican pesos) and the counsellors (monthly grant of $ 4000.00 Mexican pesos) to support their experience in entrepreneurial education (EE); 2) the IEB would provide the classrooms, projectors and materials needed to develop the EE experience; and 3) the parents or guardians of the students chosen from 5th to 6th grades of IEB had the obligation to bring them two or three days a week, at an agreed time of 4:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. to develop the project in EE ¨ [7].

The existence of the economic resources of the FESE and IES, the support of the tutors and counsellors, the participation of the parents or tutors of the small entrepreneurs, the support of the IEB and the recognition of the opportunities to offer new products and services to the community are critical aspects that will favour the creation of a micro-social environment that will encourage directors and entrepreneurs to develop knowledge, values and skills to create and manage profitable mini-companies [43].

In the creation of small businesses, the counsellors began to randomly form teams of four students of 4 and 6 IEB degrees to play the role of entrepreneur and start a mini-company; there were 8 mini-companies in total made by the IEB. Then, with the advice of the counsellors, administrative positions were defined according to the profiles presented by the students: one student was a director or general manager, another was a finance director, one was a production manager, and finally, one was a sales and marketing manager, with the aim of encouraging teamwork and internalizing the values, attitudes and knowledge of the business activity.

In this sense, there were 266 mini-companies in 2009, 480 mini-companies in 2011, 400 mini-companies in 2012, and 181 mini-companies in the biennium 2013-2014 within the 27 entities of the Mexican Republic. The states with the greatest creation of mini-companies, Chihuahua, Colima, Veracruz, Puebla, State of Mexico and Hidalgo, along with other entities, participated in the sub programme of the FESE see Figure 2.

Once the mini-companies were created, with the help of tutors and counsellors, they began to define the type of product and its costing system, as well as the mission, policies, the organizational structure of each company, the corporate image, the business logo and marketing strategies. All the achievements that were generated by the mini-companies were added to reports that were sent to the FESE for evidence of the execution of the sub programme. Then, presentations were made to the tutors, counsellors, parents and directors of the IEB, with the objective of receiving feedback and evaluating the work of the entrepreneurs.

Subsequently, the small entrepreneurs were given the task of conducting their respective market studies to monitor the potential demand in their respective places of origin. With the information gathered, they made their work plans at the same time as they were making decisions on the purchase of raw materials and the production and marketing of their products and services. The main areas to which the mini-companies dedicated themselves were the production of sweets, handicrafts, office decorations, decorated notebooks, fantasy jewellery, cosmetics, cleaning products and various foods ¨ [7].

When the mini-companies received the seed capital, which increased from $ 3000.00 to $ 1500.00 Mexican pesos because the number of small businesses created from 2009 to 2014 was growing. The economic resources available to the FESE and the HEIs did not grow at the same rate as the creation of micro-businesses. With the advice of the counsellors, the entrepreneurs began to invest, during the week, their seed capital in the purchase of inputs for the production of goods and services, and with it, on weekends, among neighbours, friends and diverse buyers, they commercialized the product. The whole process of the development of mini-companies lasted 6 months.

The economic resources were managed by the FESE through the contributions of the Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT), of the IES, and of the Chambers of Commerce (COPARMEX), among other instances, to develop the entrepreneurship not only of the entrepreneurs of the IEB but also of the young people of the IES, with the firm objective of diminishing risk aversion and uncertainty and awakening the entrepreneurial spirit in young students to face the lack of opportunities due to high unemployment rates and the increase in sophisticated technology (FESE, 2014).

In the process of entrepreneurship, learning the recording of operations in the financial statements was critical: balance sheet, income statement and financial ratios, which allowed for the healthy management of the finances and obligations of each mini-company by reinvesting the income and profits into the productive sphere and providing the micro-business with honesty and trustworthiness. In addition, promoting solidarity, respect and cooperation among the four entrepreneurs to solve the various problems and situations presented in the process of opening mini-businesses, in the purchase of inputs, in the manufacturing and marketing of various products, and in the closing and presentation of the results and experiences from the entrepreneurial project were important; the culmination of the programme was the final exhibition at the National Entrepreneurs Fair, organized by the FESE in the World Trade Center in Mexico City, Mexico, in July 2014. When the third stage was completed, the entrepreneurs evaluated whether they doubled the value of the seed capital, if it was equal or less, and drafted, with the help of the directors, the final report with the definitive financial statements and the writing of the achievements in terms of the knowledge learned, the values and attitudes cemented and/or reinforced, and finally with the fulfilment of the payment to the suppliers, to the participants of the companies, and the payment of taxes to the Treasury. In doing this, the obligations of different interest groups in the development of micro-businesses were established. At the same time, this process allowed for the development of administrative skills and values related to the productive and profitable management of seed capital.

For more than three decades, many researchers have been dealing with the relationship between the institutions of knowledge, specifically in education, experience and skills, and entrepreneurship. In this sense, the FESE promotes education in business entrepreneurship, considering that certain knowledge, values and attitudes are essential for this undertaking to be viable (Table 2).

The FESE through the sub programme created, from 2009 to 2014, a total of 1327 mini-companies ¨ [7], which are the result of learning-doing from the entrepreneurs advised by the counsellors, who were trained by the tutors, and in their exercise, they put into practice the knowledge acquired in the career of business management, administration or related careers, in addition to the practical knowledge they receive from the tutors. That is, this translates into collective knowledge that will materialize when entrepreneurs develop business ideas, producing various products from crafts, services, commerce and industry, contributing to generating important cultural baggage on the theory of business, the reinforcement and/or assimilation of values and the different attitudes that define the entrepreneur. The knowledge acquired in this way is better cemented since learning-doing allows us to remember 90% of the knowledge developed in the entrepreneurship programme, while theory only allows us to remember 10% of such knowledge (Dale, 1969).

Methodology

The study is of the quantitative and explanatory nature since it is based on the structural equation model (for its acronym in English) and the sustenance in the construction of explanatory schemes, that is, the theories that enable a better understanding of the reality and of the phenomena observed. It is also observational because it is intended to describe the phenomenon without intervening the variables that determine the research process. Cross-sectional data were handled, therefore, in the period, and in the sequence of the study, for this purpose, a survey was applied, which consisted of four questionnaires to 254 IBE entrepreneurs from 27 states of the Mexican Republic, making a cut in the time during the year 2014, with the purpose of determining the results of the social entrepreneurship of the FESE in the matter of education in the lucrative entrepreneurship of the students of IES and IEB when creating mini-companies.

The sample was intentionally non-probabilistic because it was required to obtain the largest number of entrepreneurs who formed a mini-company, of the 254 IEB surveyed as a result of the sub programme "My First Enterprise: Start a Business by Playing".

The gathering of information was based on validated instruments constructed [44] on the variables of values, attitudes and knowledge that are acquired or reinforced in entrepreneurial education, analysing the critical variables of the financial results of the mini-company and the variables related to the creation of small businesses, using a Likert scale, where 1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neither agree nor disagree, 4=agree, and 5=strongly agree.

The data obtained were systematized by determining the variables of the entrepreneurship in students from grades 4 to 6 in primary school, as well as their relationship with the creation of the existing mini-companies from 2009 to 2014 and the results obtained from the entrepreneurial process called "My First Enterprise: Start a Business by Playing." These data were first captured in the statistical software SPSS v. 24.0, and then, they were imported into the software Amos v. 24.0 for the construction of the structural equation model and its respective factorial loads.

Results and Analysis

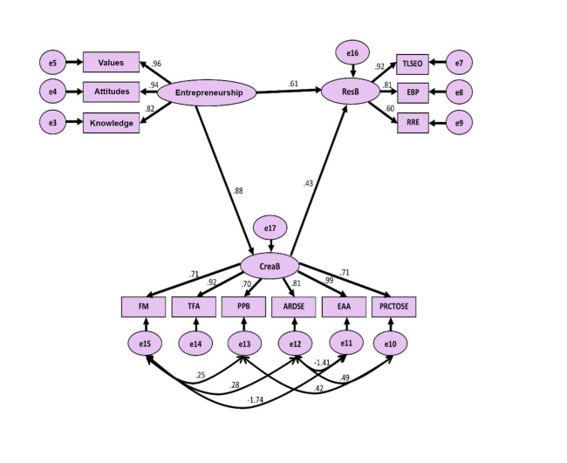

To validate the SEM, the Chi-square statistical test was performed (?2 =47.350 gl=45), and it was proven to be satisfactory (?2 /gl=1.05; p ≤ 0.05). The comparative index of adjustment (CF=0.993), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI=0.990), and the index of the approximation of the square root of the mean square error (RMSEA=0.04) concluded that these indexes of goodness and adjustment of the SEM were satisfactory and reliable.

As seen in Figure 3, the results obtained through the hypothetical structural equation model demonstrate that there is statistical evidence to affirm that the entrepreneurship developed by the IEB entrepreneurs-to develop the values, attitudes and knowledge of the business area–maintains a positive and significant relationship with the creation of mini-companies as a vehicle for entrepreneurial learning (b1=0.88; p <0.001), supporting hypothesis H1. Similarly, entrepreneurship is positively and significantly related to the favourable results of the mini-companies (b2=0.61; p <0.001), and these results in turn are explained by the learning translated into the opening of small businesses through the game, the execution of the business plan and the reporting of the business results. The creation of mini-companies is linked in a positive and significant way with these results (b3=0.43, p <0.0001) and is explained by the formation of mini-companies, the training of the directors, the production guided by the business plan, the administration of resources to develop small businesses, the efficient attention of the counsellor towards entrepreneurs and the conclusion: the programme represents a change in the opening of small businesses, supporting hypotheses H2 and H3 in this way (Figure 3).

Table 3 shows the factorial loadings of the variables and shows results greater than 0.5, which implies that the variables are highly significant, and ultimately, the crucial requirement is located in two stages: one is at the theoretical level, which means that there must be a sufficiently solid basis justifying the transition from covariance to cause-effect relationships, and another level, which is the methodological level, in which researchers must be able to mathematically specify models that adequately represent the theoretical mechanisms involved in the data, choosing which parameters are to be set from the theoretical background and which are to be estimated from the data. The SEM is limited to evaluating the causal model designed by researchers based on the theory of social and lucrative entrepreneurship, in which three latent variables are detected - as in the case of entrepreneurship, the variables that positively influenced the enterprises and the favourable results of them-whose independent variables represent a set of relations observed and consistent with the theory indicated [45].

In this sense, as far as the FESE is concerned, it has orchestrated human and technical resources to facilitate the process of education in the opening, development and closure of small businesses, where there is collective knowledge transfer between an important constellation of educational institutions, thereby developing intelligent education about the theory of business and the values that accompany it to develop new skills and knowledge for life.

A key avenue for the business development and incubation of small businesses is entrepreneurship education [46]. Entrepreneurship education has taken a strong turn in recent years, especially for developing countries, considering that it promotes skills, attitudes and values to deploy competencies for the individual to take initiatives that drive change.

From the philosophical point of view, entrepreneurship is innate in the essence of the human being since it is present in each of the actions it develops to seek transformation and improve its living conditions. However, similar to many other human qualities, entrepreneurship needs to be consolidated through education [47] states that "we are born entrepreneurs, but education can facilitate the process of materializing our good ideas in all fields of our intellectual and professional life as it makes us improve our activities and skills to undertake." Entrepreneurship, according to [47] is the set of attitudes and behaviours that generate a personal profile linked to risk management, creativity, capacity for innovation, and self-confidence and directed to entrepreneurial action. It focuses on an innovative action that, through an organized fabric of interpersonal relations and the combination of resources, is geared towards a specific objective. It is related to the creation of something new that creates value through the production of a good or service, which previously did not exist, taking a risk for this initiative. Europeans' concern for unemployment has led to this term being highlighted as a way to create a broadly competitive social economy [48].

To measure the financial effectiveness of the sub programme and according to FESE data (Table 4), the total number of enterprises created by children entrepreneurs in the 27 states of the Mexican Republic was 266 small businesses in 2009; in 2011, there were 480 businesses; in 2012, there were 400 businesses; and in 2013-2014, there were 181 businesses. There was a total of 1,327 companies. Of these companies, 78.9% obtained lower profits than seed capital; 13.3% reported higher profits than seed capital; and 0.9% generated zero profits. Of all the companies, 88.6% of the small businesses recovered seed capital from their investment. These figures tell us that entrepreneurial activity maintained good dynamism by maintaining an average annual growth of 10.7% in the creation of small businesses with low levels of losses (Table 4). Therefore, these indicators show us that the process of entrepreneurship training in children is successful, which means that preparing children from a young age with the human resources capable of undertaking new businesses aimed at creating wealth will ensure the creation of jobs and improvement in the standard of living.

To measure the financial effectiveness of the sub programme and according to FESE data (Table 4), the total number of enterprises created by children entrepreneurs in the 27 states of the Mexican Republic was 266 small businesses in 2009; in 2011, there were 480 businesses; in 2012, there were 400 businesses; and in 2013-2014, there were 181 businesses. There was a total of 1,327 companies. Of these companies, 78.9% obtained lower profits than seed capital; 13.3% reported higher profits than seed capital; and 0.9% generated zero profits. Of all the companies, 88.6% of the small businesses recovered seed capital from their investment. These figures tell us that entrepreneurial activity maintained good dynamism by maintaining an average annual growth of 10.7% in the creation of small businesses with low levels of losses (Table 4). Therefore, these indicators show us that the process of entrepreneurship training in children is successful, which means that preparing children from a young age with the human resources capable of undertaking new businesses aimed at creating wealth will ensure the creation of jobs and improvement in the standard of living.

Conclusions and Final Reflections

The FESE was created to help with the creation of micro-businesses to manage new ways of transforming society for several reasons: 1) the FESE comes into play as an effect of the global crisis arising from the contradictions of globalization in 2007 and 2008: climate change, economic crisis, food crisis, energy crisis, rising unemployment and organized violence; 2) the FESE orchestrates resources, capacities and institutional efforts of private and public organizations, aimed at creating self-employment through the emergence of micro-enterprises, especially when there are more problems arising from the market and government governability. The creativity is manifested in the micro-enterprises promoted since primary school, where the work of tutors and advisors of the HEIs is concretized. In addition to knowledge, values and business management skills are also transferred by creating an increasing number of mini-enterprises from 2009 to 2014, which recorded a growth of 1,327 companies, mainly in craft making, food and marketing activities.

Building an economy for people means that entrepreneurship becomes the basis for generating wealth and jobs by creating new businesses for populations in conditions of social backwardness [49-53]. Because the state is discharging to civil society organizations, there are some strategic functions for community development. A key avenue for the business development and incubation of small businesses is entrepreneurship education [53-57]. Entrepreneurship education has taken a strong turn in recent years, especially for developing countries, considering that entrepreneurship promotes skills, attitudes and values to develop competencies for the individual to take initiatives that promote change.

With regard to the limitations presented in the study, it was difficult to ascertain which levels of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values were developed before and after the sub programme and to precisely know how they advanced at those levels. However, this study opens up a rich beta for the further analysis of multidisciplinary studies relating social entrepreneurship to education in lucrative entrepreneurship, now that there is an urgent need to develop entrepreneurial culture in young students and to intelligently train entrepreneurs to positively impact their environment.

With regard to the limitations presented in the study, it was difficult to ascertain which levels of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values were developed before and after the sub programme and to precisely know how they advanced at those levels. However, this study opens up a rich beta for the further analysis of multidisciplinary studies relating social entrepreneurship to education in lucrative entrepreneurship, now that there is an urgent need to develop entrepreneurial culture in young students and to intelligently train entrepreneurs to positively impact their environment.

Recognitions

Acknowledgements to the University of Guanajuato for supporting its full-time researchers, such as those master and doctoral students who, with all their effort and dedication, are studying for their respective postgraduate degrees.

Recognition

Acknowledgements to the University of Guanajuato for supporting its full-time researchers, such as those master and doctoral students who, with all their effort and dedication, are studying for their respective postgraduate degrees

Figure 1: Actors involved in the sub programme: "My First Enterprise: Start a Business by Playing".

Figure 2: Entities of the Mexican Republic (indicated with bullets) where the sub programme of the FESE was undertaken, from 2009 to 2014; see * [7].

Figure 3: Hypothetical SEM.

|

Name of the entrepreneur child |

Age |

Project |

Project description |

|

1. Ashley Qualls, |

14 |

Website called: Whateverlife.com |

Designed to provide ready-made Myspace designs and HTML tutorials for people of your age. |

|

2. John Koon |

16 |

Autoparts |

He opened his firt auto parts business in New York at age 16. Koon made millions when his company, Extreme Performance, Motorsports, became the main provider for the MTV reality show Pimp My Ride. |

|

3. Cameron Johnson |

9 |

Online advertising and software development |

When he was only 9 years old, Cameron Johnson launched a greeting card company called Cheers and Tears. By the time he got to high school, Johnson swithched to online advertising and software development, which assured him a monthly income of about $400,000.00 |

|

4.- Adam Hildret |

14 |

Marketing agency for youth |

Hildret is now the mind behind Crisp Thinking, a company specializing in technology to ensure children´s digital security for internet service providers. |

|

5.- Evan Tube |

8 |

Youtube Channel |

EvanTube makes toy reviews and works on things that interest kids of that age. The channel earn average of 1.3 million dollars a year. |

|

6.- Juliette Brindak |

10 |

Cartoon characters |

He started at age 10, eventually resulting in a social interaction site for teenagers when he was 16. It is estimated that his company Miss & Friend is worth 15 million dollars, which mainly comes from advertising. |

|

7.- Tyler Dikman |

5 |

Lemonades-computer Repair |

By the time he was 15 he launched Colonics, a computer repair business. In 2 years, by 2001 it was worth millions of dollars. |

|

8. Christian Owens |

14 |

With Mac Bundle Box Offered applications for Mac. |

That they were simple and discount, after negotiating with developers and manufacturers. He also founded Branch. |

|

9. Adam Horwitz |

15 |

Hurwitz found success with Mobile Monopoly |

An app that teaches users how to make a profit with the potential customers of the mobile market. In addition, the text advertising service began. |

|

10. David y Catherine Cook |

12,14 |

Website |

It focuses on helping users find new people to chat on mobile devices. |

|

11. Nick D’Aloisio |

17 |

Designed the smugly app |

Summly is an automatic sums algorithm that you sold to yahoo for US $ 30 million. |

|

12. Farrhad Acidwalla |

16 |

Rockstah Marketing Agency |

Rockstah marketing using 10 dollars that his parents gave him, now he is a multillionaire investor and speaker in TEDx. |

|

13. Maddie Bradshaw |

10 |

M3 Girl Desings |

She presented her idea on Shark Tank and wrote her own book: Maddie Bradshaw´s You can start a Business, Too. |

|

14. Sean Belnick, |

15 |

BizChair.com, |

BizChair.com, one of the first online stores selling office furniture. For 2005, the company reported sales of 13.6 million dollars and remains profitable to this day. |

|

15. Ryan Kelly |

11 |

Shark Tank |

Confectionery for dogs. The company is still operational, but has been renamed Ry´s Ruffery. |

|

16. Isabella Barrett, |

9 |

Glitzy Girl y Bound by the Crown Cou |

After making a name for herself on the Toddlers and Tiaras show, Isabella Barrett launched her own line of jewellery and clothing, Glitzy Girl. |

|

17. Kiowa Kavovit |

6 |

Boo Boo Goo, who paints bandages on cuts |

She had the courage to appear in Shark Tank and Present and present Boo Goo, Who paints bandages on the cuts. |

|

18. Fraser Doherty |

14 |

SuperJam. Jams |

He started making jams using his grandmother´s recipe. Since then he has founded 2 other companies Envelope Coffee and Beer. |

|

19. Mikaila Ulmer, |

11 |

Lemonade “Me & The Bees" |

Sell your lemonade at 55 Whole Food stores in Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Luisiana and Florida. She donates part of her sales to organizations committed to the preservation of bees. |

|

20. Robert Nay |

14 |

Play with your Bubble Ball app |

It became the sensation of the night when he was 14 years old. In fact, the game has been positioned for 2 weeks at million. Today, Nay continues to develop games at his company Nay Games. |

|

21. Madison Robinson |

15 |

Fish Flops |

Originally, the business only sold flip flops with designs for 2 weeks at 2 million. Today, Nay continues to develop games at his company Nay Games. |

|

22. Jack Bonneau |

8 |

Jack’s Marketplaces & Stands |

"She sells her lemonade". The company supports other young entrepreneurs helping them to start having their own stand and obtain the necessary insurance, permits and supplies. |

|

23. Farrah Gray |

14 |

Farr-Out Food |

By the time he turned 14, the company was worth 1.5 million dollars. Today Farrah is also an investor, author, columnist and motivational speaker. |

|

24. Cory Nieves |

10 |

Mr. Cory’s Cookies in 2009 |

Mr. Cory´s Cookies started in 2009 as a stand that came with hot chocolate, cookies and lemonade. Unfortunately, the health department closed it. So, what did this little one do? He legally incorporated the business, created his own recipes and is now a 10- year-old CEO". |

|

25. Gabrielle Jordan |

9 |

Excel Youth Mentoring Institute |

He created the Excel Youth Mentoring Institute, where he began to mentor other children who also want to start their own businesses. |

|

Note: Source: (Entrepreneur, 2016). |

|||

Table 1: Success stories of entrepreneur children.

|

Year |

Values |

Attitudes |

Knowledge |

|

2009 to 2014 |

It develops in the children's community the sense of work, its fruits and its repercussion in daily life. Raises awareness among children about the purpose of generating money with social and environmental responsibility. Acquisition of values: respect, tolerance, responsibility, reciprocity, teamwork, solidarity, honesty, cooperation, punctuality, etc. Entrepreneurs were motivated by work in their mini-companies , and they realized the value of effort, teamwork and responsibility, aspects that made the teams work through their organizational structure, the directors were proud of their team and recognized the effort of the IEB for having impelled them to participate in this programme by realizing the equitable distribution of income among the members of the mini-companies. In addition, from the simulation of the payment of taxes corresponding to the delivery of the seed capital to the primary school so that it would cover needs for didactic material and stationery, encouraging the help and support to the neediest, etc. The small entrepreneurs contributed not only in the acquisition of new knowledge but also in personal aspects such as security, self-esteem and pride in having contributed with their work and effort to improve and benefit their school. |

Leadership and commitment. Development of skills in sales, production, administration, finance and marketing for the sale of the product that allowed for the socialization and knowledge of their capabilities. Learning based on team building. Development of entrepreneurial skills such as initiative, attitude, and aptitude towards innovation. The entrepreneurial children, after having participated in this subprogramme, showed a sure attitude of themselves, with knowledge and total comprehension of the concepts they learned about the formation of a company. |

Know the bases for the creation of a small company. Creativity for the design of their products and the development of the entrepreneurial culture in the locality. |

|

|

|

From the ages of 8 to 12 years, entrepreneurs noticed the presence of conflicts to try to solve several problems at the same time, but they assimilated that with peace and tranquillity they could work in a better way, and since there was no exam, a playful work through which learning by doing was facilitated, they realized the importance of working together and their high capacity for reconciliation, which gave them the ability to reorganize to present their results at each stage of the process opening, development and closing of the mini-business. |

Acquire a business language, detection of business opportunities, application of knowledge obtained during his/her life, in a real project that would allow for the development of skills in sales, production, administration, finance and marketing. This programme aroused great interest in children since some activities were carried out in basic education schools: the closure, the sale of products, and the distribution of the recovered capital. This experience led the children to express their desire to study at the university, in addition to wanting to create their own company, being a seed that was planted and that in the future will pay off. They assimilated concepts such as balance point, values, mission, vision, seed capital, utility, promotion, slogan, etc. IEB students developed entrepreneurial skills, and their life project was fostered through ideas to develop productive projects at any age, and the idea of ??studying a profession was encouraged and strengthened thanks to the example of their advisor. In addition, social skills were developed through the relationship with an adult guide and acquired knowledge of altruism by supporting their own school through the donation they made, the effect of their sales profits. |

|

Note: Source: FESE, 2014. |

|||

Table 2: The values, attitudes and knowledge fostered by the "Start a Business by Playing" programme for entrepreneur children.

|

Entrepreneurship=Variable of entrepreneurship |

Factor loadings of the items |

|

Values |

0.96 |

|

Attitudes |

0.94 |

|

Knowledge |

0.82 |

|

ResB=Variables of the favourable results of the mini-companies |

Factor loadings of the items |

|

TLSEO=learn to open small businesses through the game |

0.92 |

|

EBP=execution of the business plan |

0.81 |

|

RRE=business results report |

0.6 |

|

Variables in the creation of small businesses |

Factor loadings of the items |

|

FM=training of micro-companies |

0.71 |

|

TFA=training of counsellors |

0.92 |

|

PPB=production based on the business plan |

0.7 |

|

ARDSE=administration of resources to develop small businesses |

0.81 |

|

EAA=efficient attention of the counsellor towards entrepreneurs |

0.99 |

|

PRCTOSE=the programme represents a change in the opening of small businesses |

0.71 |

Table 3: Variables and factor loadings.

|

Characteristics |

Year |

||

|

2009 |

2011 |

2012-2014 |

|

|

Companies created by children |

266 |

480 |

400 |

|

Companies with seed capital recovered |

20.80% |

74.30% |

54.50% |

|

Companies with undiscovered seed capital |

35.80% |

33.80% |

37.50% |

|

Companies reported without social status information |

10.00% |

12.00% |

8.00% |

|

Companies with seed capital recovered |

|||

|

Profit < seed capital |

* |

88.60% |

78.90% |

|

Profit > seed capital |

* |

13.30% |

|

|

Profit = seed capital |

* |

0.90% |

|

|

Without earnings |

* |

6.90% |

|

|

Note: *Missing data available, Source: New York, 2014. |

|||

Table 4: Financial information on the development of companies generated by children through the Mi Primer Empresa programme: "Emprender Playing" at the end of the fiscal year.

Characteristics of the years 2009, 2011, and 2012-2014.

Citation: Cárcamo-Solís ML, Serrano-Torres MG, Acevedo-Arcila IA, López-Lemus JA (2020) Social Entrepreneurship: An Approach to Education in Entrepreneurship in Mexico. Int J EducAdv: IJEA-100004